Surveys

DJC.COM

November 15, 2001

A peek into the architectural process

AIA Seattle

Sackett |

It’s natural to view architecture as buildings, and never ask how they got there.

Seduced by the landscape, and in our haste to get to the point, we make a perfunctory scan of the details. But to disregard the rich process by which an idea becomes a place is to miss most of the story. At the end we may know the facts, but not why they matter.

Architecture is more than a tangible object — it is a long, complicated performance that transforms inspiration into physical substance.

And stretched somewhere between concept and construction is a perilous and dramatic journey that the public may often overlook. The AIA Seattle Honor Awards for Washington Architecture gives a name to this journey — “not yet built.”

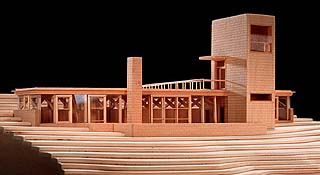

Photo courtesy David Coleman Architecture The Collins-Thompson Residence, by David Coleman Architecture, is an award-winning residential project with an uncertain future. |

On Oct. 22 at Benaroya Hall, architects Steven Erlich of Los Angeles, Brian MacKay-Lyons of Halifax, Nova Scotia, and Maryann Thompson of Boston weighed publicly the merits of 175 anonymous projects submitted by Washington architects. Before announcing their final selections, the jurors had spent several days scrutinizing photographs, reading design statements and making site visits to learn the stories behind the projects.

This competition — the largest and most ambitious of its kind of any AIA chapter — is designed to be as inclusive as possible. The Honor Awards program guidelines create three entry categories: “Conceptual,” “Completed” and the cryptic “Not Yet Built” group.

The Conceptual and Completed classifications are self-explanatory. A not yet built project is an as-yet unfinished commissioned work. The single new element — a client — propels the undertaking beyond the conceptual stage, engaging a wide variety of fresh influences. The project has left the amniotic fluid of imagination to grapple with the challenges of a practical world.

The name for this category of nascent works was selected by the Honor Awards committee to demonstrate that architectural projects don’t emerge from the mind of an architect fully formed, instead taking shape over time.

In many, if not all, artistic fields, artists are unwilling to allow people to see their work before they have finished. But in this unusual intermediate exposure, a project’s awkward formative stage is celebrated instead of hidden. In this context, therefore, the word “yet” is not an apology, it is suspense.

The not-yet-built projects represent a narrative — the liner notes — of works in progress as they move from the pretend to the real — the evolutionary process of architecture-in-motion. When architect and client come together, factors begin to converge. The challenge here for the architect is to orchestrate the project to completion, maintaining the vision that made it compelling in the first place.

Architect David Coleman, co-chair of this year’s Honor Awards committee, submitted several not-yet-built projects for consideration. The jury selected his Collins-Thompson Residence, a second home designed for a Lopez Island site, for commendation.

Coleman believes it is the primary responsibility of the architect to do two things at this stage of a project’s development — pursue the mission of making the client happy, and maintain the focus of the concept. “Once they’re into it and you’ve got it nailed,” said Coleman, “it’s the role of the architect to be a conductor and make sure the concept stays alive.”

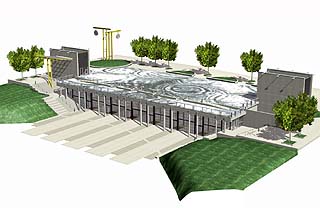

Image courtesy The Miller-Hull Partnership Despite radically different programs, the Honor Awards jury underscored the similarities between the Collins-Thompson Residence and The Miller-Hull Partnership’s Fisher Pavilion, above, by referring to them as “the buried projects.”

|

This is a dramatic time, as well, in the life of the project. Any number of external elements can change to irrevocably affect the outcome. Budget constraints and adjustments occur; changes in cost and availability of essential materials or the priorities of the client are not unusual.

And even if a project receives an award, its future is still uncertain. The Collins-Thompson Residence won a commendation, but Coleman confided that the client decided to return to graduate school, putting the entire endeavor on hold indefinitely.

Coleman, however, remains determined. “This will be built,” he emphasized.

Here is the unique occasion to witness how an architect grapples with the forces that can enhance, diminish or demolish his work. “The parameters become actual,” said Coleman. “There are so many opportunities to screw it up.”

Coleman believes the not-yet-built category is important, since there can be a significant lag time between a project’s start and finish. “Part of why I entered it,” he said, “was to keep the momentum going.”

Although this year’s not-yet-built selections are very different kinds of projects, they have some substantial parallels.

For example, the two singled out by the jury this year have dissimilar programs, but some striking similarities in form. The aforementioned Collins-Thompson structure is a private residence. The Fisher Pavilion by The Miller-Hull Partnership is a renovation of a multipurpose space at Seattle Center.

Though notably different in scale, both are long, simple rectangular boxes emerging broadside from a sloped landscape.

In showcasing these juxtapositions, the category makes an additional contribution, as Coleman agrees.

“It’s an important barometer that shows where the profession is going,” he said.

Image courtesy LMN Architects The Reno-Sparks Convention Center addition and renovation by LMN Architects appeared in the Honor Awards first as a conceptual entry, then a not-yet-built project, and is now only a few months from completion. |

When the year’s submissions are viewed all together, patterns can emerge, reflecting trends on their way in or out. Even the number of submittals can have significance. All these elements help to write the design history of the region.

Lastly, these not-yet-built entries afford an interesting teaching opportunity for participants and audience alike. Within the context of the Honor Awards, the jury comments can be constructive and utilized like a critique. At this stage, it’s not too late to make adjustments that can strengthen the project. And regardless of whether a design comes to fruition as a completed work, the architect has worked out an equation to which he can return.

The AIA Seattle Honor Awards Web site accumulates and catalogs all the projects submitted to the annual competitions.

Most projects progress through all three stages. For example, the Reno-Sparks Convention Center expansion and renovation by LMN Architects appeared first as a conceptual entry two years ago, proceeded to the not-yet-built stage where it won an award, and is now just a few months from completion.

The Web site presents these works in states of suspended animation. Like Eadweard Muybridge’s 19th century sequential photographs of human and animal locomotion, the images describe the attitudes each entry assumes in its progress from concept to completion.

Goethe described architecture as “frozen music.” Investigating the not yet built designs is like finding that music while it’s still in its liquid state.

Peter Sackett can be reached via e-mail at psackett@aiaseattle.org.

Other Stories:

- Orchestrating Belltown’s rebirth

- Getting a project off the ground

- Head and shoulders above Sea-Tac

- High-rise homes with all the right stuff

- So you’re in it for the money

- What you need to know about your competitors

- Thea’s Landing: Downtown Tacoma’s new urban housing

- Rebirth of a Commencement Bay chateau

- New museum will have Tacomans glassy-eyed

- Beyond the urban core: Learning from the pioneers

- Achieving design certainty through collaboration

- Controlling stormwater the natural way

- Mechanical moxie: Innovations at the new Opera House

- Preserving a church gets personal

- Small housing: A Northwest mini-trend

- Delivering the goods in a tight economy

- Don’t overlook moisture — the silent threat

- Designing a one-building ‘city’ on a Norwegian fjord

- The changing face of retail design

- Preserving affordable housing by design

- A cap over troubled waters

- Hospitality industry draws on refuge and prospect

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.