Surveys

DJC.COM

October 26, 2006

Seattle’s waterfront: 100 years of hidden history

RoseWater Engineering

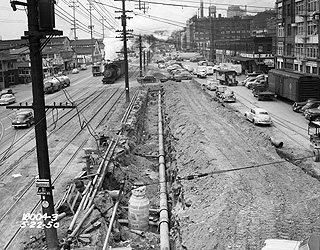

Photo courtesy of Seattle Municipal Archives

Infrastructure has been piecemealed over the years on the Seattle waterfront, including this 1950 sewer replacement project along Alaskan Way south of Columbia Street.

|

When it comes to the future of Seattle’s vital infrastructure, few projects have captured as much public interest as the Alaskan Way Viaduct and seawall replacement project. While the two final alternatives are under consideration, there is a very complex task already under way, a necessary component regardless of the alternative finally constructed.

That component is relocating the area’s critical utility infrastructure, including the electrical, water, sewer, drainage and other hidden systems.

Several challenges surrounding the utility relocation make this task more than a little arduous. In addition to moving the systems that serve the city’s daily operations (if any one system is not functional, the city would be unable to operate), most of the work will be done with the existing viaduct and facilities in place, leaving restricted space for construction. The viaduct limits overhead clearance for construction machinery, and nearby businesses are nestled right up against the structure.

Further, a majority of the work will be done in and around historic structures that must be protected.

Photo courtesy of RoseWater Engineering Natural gas lines were replaced last month under the viaduct south of Columbia Street.

|

Unearthing the past

The Seattle waterfront has a long and glorious history. It was a trading post for many, a stopping point for provisions, and an industrial shipping port. The city’s industrious past adds to the complexity of the existing utilities, since over the years the systems have been added to, modified, and partially removed to accommodate current activities on the waterfront.

This is often referred to as the Frankenstein approach to utility construction. Patch in a piece here, add a little bit there, provide some connections, and over time the systems can become very complicated. The Seattle waterfront has experienced this approach for more than 100 years. Even systems that were in place prior to the downtown fire in 1889 were retained and modified afterward to continue providing services to a rebuilding city.

Over the years, even the shoreline has been changed. The installation of the seawall from the early 1900s through 1930s, fills from the Denny Regrade, and other local projects have impacted the waterfront area. This becomes significant because excavations necessary for the installation of utilities will be going directly through fill over the former shoreline area.

Photo courtesy of RoseWater Engineering

The jobsite below the viaduct has restricted vertical clearance for construction equipment. |

Invisible lifelines

When most large-scale construction projects are discussed, it is often with bravado, in terms such as the “biggest” or the “most complicated,” or even “the most impact and improvement.” For utilities construction, the impacts of the work should be invisible to both the utility service providers and the customers. Phones should still ring, water should still flow and toilets should still flush — a significant challenge when dealing with a project that could result in digging a tunnel between the service and the customer.

Because of the restrictions and complexities of existing structures and systems, innovation is essential when it comes to installing and constructing the utility systems. Directional drilling, reduced-height equipment and adjustable shoring systems are all methods that will help ensure seamless construction.

Photo by Ben Minnick The “lump” on Yesler Way from Western Avenue to First Avenue is a change in grade caused by the debris left from the Seattle fire of 1889. Utility relocation will go directly through fill areas such as this one. |

When relocating a utility, the plan is to construct a secondary utility that will take the place and functionality of the system that is currently in the way of the Alaskan Way Viaduct replacement alternative. Once this second utility is installed and operational, the other utility can then be abandoned and removed during the replacement alternative construction. For some utilities, temporary services will be placed either ahead or behind current construction work, allowing the service to remain as transparent as possible to the customer through the entire construction process.

| Utilities impacted |

|

The Alaskan Way Viaduct and seawall replacement project will impact many utilities feeding Seattle, including:

• Electrical transmission (power connections between substations) • Electrical distribution (power to service connections and customers) • Water (for drinking and fire suppression) • Gravity systems (sewer, combined sewer and storm drainage) • Communications (telephone, cable television and fiber-optic cable) • Natural gas (for heating, cooking and industrial services) • Steam (a source of heat for piers and other facilities) • Petroleum (primarily for emergency back-up systems) |

Better systems for the future

Another significant aspect of the work is to bring utility systems into compliance with current codes, reduce or eliminate redundancies, and streamline system maintenance. This is accomplished by the design team working in close coordination with the utility agencies and the city as the utility designs move forward.

This coordination ensures current system functionality is maintained, and that the utility agencies are prepared to operate and maintain the modified systems. By coordinating early in the project, the need for re-design work can be minimized.

Finally, the utility relocation work must be coordinated with the surface restoration, and must fit within the larger goal of improving the city’s waterfront. The final part of the utility installation will require innovation and creativity to achieve.

Working closely with the team designing the surface restoration along the waterfront, the utility engineers will use model drainage systems such as bioswales, rainwater recovery, and other sustainable features to effectively integrate the utility systems into the urban environment.

Long after the viaduct alternative is constructed, this carefully designed utility relocation work will ensure the city’s vital systems will continue to function invisibly and seamlessly, serving Seattle’s current and future generations.

Charles Smith, PE, has 20 years of experience in civil engineering design, specializing in sanitary engineering, water resources, hydraulics and hazardous waste engineering. RoseWater Engineering has been coordinating utility relocation and is designing water and drainage modifications for the Alaskan Way Viaduct and seawall replacement project.

Other Stories:

- Victoria project goes from brown to green

- Retail plays a bigger role in mixed-use

- In with the old, in with the new

- Designers bet urban dwellers want more

- Dream team designs downtown penthouses

- Designing a cancer center for 4 competitors

- Healthy buildings’ role in organic modernism

- Queen Anne readies for icons old and new

- Keeping the bad guys out of banks

- Surviving today’s tough bid climate

- Why marketing during the good times is critical

- Getting creative with your feasibility analyses

- Hotels and condos: mixed-use matrimony

- School’s design reflects its humanist curriculum

- Should design firms grow and change?

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.