|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Architecture & Engineering

| |

August 29, 2016

Seattle testing a new material for synthetic turf fields: cork

Journal Staff Reporter

Seattle Parks and Recreation has 26 synthetic turf playfields throughout the city, and they all need to be replaced from time to time.

Until recently, they all had an artificial topsoil layer made up of crumb rubber, a material made from recycled car and truck tires.

But now the city is testing an organic alternative: cork.

Seattle Parks opened its first cork-infill field three weeks ago at Cal Anderson Park on Capitol Hill.

FieldTurf USA installed the roughly 100,000-square-foot surface on the Bobby Morris Playfield.

Jay Rood, a Seattle Parks project manager, said the field is a pilot project that will test the new material for durability, safety, playability, maintenance and environmental health.

Synthetic turf has been around for more than 50 years. Though early versions were “a kind of high-tech padded carpet laid over a base of asphalt,” as the New York Times put it in 2003, synthetic surfaces have become more sophisticated over the past couple of decades.

You could even describe the newest systems as rather complicated.

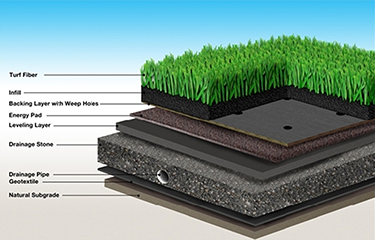

The Synthetic Turf Council, an industry trade group, shows on its website a cutaway illustration of a contemporary field that has seven layers: geotextile, drainage stone with piping, a leveling layer, an “energy pad,” a backing layer with weep holes, infill and, finally, the “grass,” which it calls turf fiber.

The result is ideally a synthetic field that drains well, holds up through years of heavy use, and feels more or less like grass. Compared with natural grass, synthetic turf also doesn't require as much irrigation or maintenance.

But not everyone feels safe playing on turf with crumb rubber infill. For example, the Edmonds City Council voted last year to temporarily ban the material in new public playfields after community members expressed concerns about its long-term health effects.

Three federal agencies are working together to investigate whether crumb rubber poses health hazards, such as by releasing toxic chemicals through contact with sweat or skin. That's one of a number of health evaluations underway. So far, studies haven't validated any concerns.

Still, Seattle Parks wants people to feel safe playing on its synthetic surfaces and allow their children to play on them without worry.

“We want to lighten the level of anxiety,” Rood said.

The Parks department evaluated several alternatives to crumb rubber, including cork, coconut husks, a sandy material, and TPE, a nontoxic plastic that performs like rubber. The department ultimately chose cork for its durability and resistance to fungal growth, and because it won't need irrigation. (If you're wondering why synthetic turf would need to be watered, it's because the infill — depending on the material — can get hot or dry out.)

So far, feedback about the cork-infill field has been positive, Rood said.

Some feared the surface “would feel like walking on a bunch of wine corks,” he said, but the reality has been less novel.

“It has a little denser feel” than the crumb rubber, Rood said, but “the ball seems to bounce well.”

The old Bobby Morris Playfield surface was 11 years old and due for a replacement, but cork infill does come with extra cost.

The $1 million installation was 24 percent more expensive than the cost of a synthetic field with crumb rubber infill, Rood said.

A big chunk of the extra cost has to do with a shock-absorbing underpad that was installed as part of the turf system. Rood said the pad can be reused the next time the turf has to be replaced. The field has an eight-year warranty.

He said he expects costs will drop as infill options become more competitive.

The Parks department will test the field over the next year. Monitoring will cover items such as water quality, mold, wear patterns, ease of maintenance, and the field's ability to absorb shocks.

If testing goes well, the Parks department could continue to install cork fields.

Rood said the city must replace a synthetic field or two every year. A typical field lasts eight to 10 years.

“It's a transitional time for recreational fields,” Rood said, considering the growing number of infill options available. “We're fortunate Seattle is able to invest in this.”

Jon Silver can be

reached by email or by phone

at (206) 622-8272.