|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Construction

| |

|

August 21, 2003

America’s ongoing school-building crunch

FMI

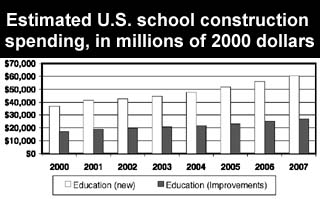

(Source: Building permits, construction put in place and trade sources. Estimates and forecasts by FMI.)

School construction spending in the U.S. is expected to continue climbing through 2007, when it reaches nearly $90 billion. But the pace may not be enough to keep up with current needs.

|

A few basic phenomena are driving the need for new and refurbished schools.

According to the 2000 census, the U.S. population increased 13.2 percent in the 1990s. Enrollment in public schools rose at an even greater rate, increasing 20 percent from 1985 to 2001, according to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).

The fact that these increases were not equitable across the states — most of the states in the South and Southwest had population increases greater than 20 percent — has put even greater strains on existing school infrastructures.

Add to the population growth and redistribution problems the fact that, even though we have been building schools at a record pace in the past decade, most existing schools were built in the 1950s.

According to the 2000 National Education Association (NEA) report, “Modernizing Our Schools: What Will It Cost?” rebuilding or repairing school infrastructure to meet current (2000) needs would cost $268.2 billion. At the current pace for school construction, we wouldn’t be caught up to 2000 needs until around 2006.

Assuming another 7 percent population growth by that time and the number of schools entering the major-maintenance-project phase, we estimate that it will likely take until around 2010 before we have alleviated the crisis that started in the early 1990s. But that is only if we can at least maintain the current levels of construction — and it’s not certain that we can.

Containing costs

Thanks to the efforts of local citizens groups such as PTAs and national associations and government groups like the NEA and NCES, the message that we desperately need to update our education infrastructure has been widely received and acted upon.

Nonetheless, education funding, building design, and other political decisions take time. Too often, between the time the initial estimate is made and the final go-ahead is given, there are “unforeseen” cost escalations and other regulatory considerations that come into play.

From President Bush’s budget plan for schools, the 2001 NCLB Act, named after the slogan, “No Child Left Behind,” to the budget crunch being felt by states and municipalities across the nation, anything to do to with our nation’s schools can become a political hot potato or a source of immense pride, and often both.

Among other things, this situation means that contractors in the education market must have a deep understanding of both national and local issues. While local school board members may not be adept at the language and methods of construction, they are aware that schools too often tend to cost more than the final bids and take longer to build than planned.

Architects, construction managers, and contractors can all help to educate the owners and learn what the needs of the community are.

For instance, many communities have found that they can combine their needs for community-meeting and recreation facilities with their plans for new schools. The advantages are cost spreading and higher building use, as well as the added benefits of better school facilities and, potentially, a closer community.

Helping the trend toward more-efficient building is the fact that most states, including Washington, now allow some form of design/build as a delivery option.

Private schools

One of the novel and controversial features of the NCLB Act is the provision for redirection of federal funds toward allowances for private school tuition if a child becomes "trapped" in an underperforming school or a school that doesn’t meet federally mandated state guidelines for academic performance and safety. This is not the voucher program that the Bush administration dreamed of, but it does increase the chance that private schools will play a greater role in our education systems in the future.

For now, private education enrollments are not increasing and, even though the largest operator of private schools, Edison Schools, headed up by Christopher Whittle, has landed a large contract with the Philadelphia school system to directly manage 20 schools. The original proposal was for more than twice that. The idea is still considered experimental.

As a public company founded in 1992, Edison Schools has yet to make a profit, and Whittle announced plans last month to take it private.

Nonetheless, the company said it has received the critical recapitalization necessary to carry out the Philadelphia plan.

Also, in spite of some stellar results, not all of Edison Schools’ projects have increased test scores to the extent promised or at a pace faster than comparable public schools. On the other hand, magnet schools remain an interesting alternative in many metropolitan areas where they are allowed.

Leaving the 1950s behind

Many new schools will look as different as the multi-room brick buildings of the 1940s and 1950s looked from the one-room schoolhouse.

Besides being wired for Internet and Intranet connectivity, new schools are likely to be air-conditioned and often carpeted. Air conditioning, even in northern climes, is a means of improving air quality in the building, recognizing the increased incidence of asthma in children as well as benefits to learning and teaching and considerations for year-round teaching schedules.

Other amenities such as recreation facilities and theaters may be included in partnership with the community to not only increase efficient use of the building, but to encourage community involvement in education. There is also a movement, in part funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, to encourage small “early college high schools” as opposed to recent trends for larger, centralized schools incorporating several existing school systems.

Where the trends that shape the next generation of schools ends up is not yet clear. Probably we will not have one clear type of school or solution as we had in the 1950s. Rather, we will continue to try new ideas and to build schools that fit community needs while focusing on efficiency of construction and effectiveness of instruction.

(This is a longer version of the article that appeared in the print edition. The section about private schools was not included because of space constraints.)

Phil Warner is marketing coordinator for FMI Corp., a management consulting group for the construction industry. Contact Warner at pwarner@ fminet.com or (919) 785-9357.

Other Stories:

- Tomorrow’s schools could be neighborhood hubs

- New standards will help schools go green

- Keeping up with the Joneses

- Value engineering pays off for Seattle Schools

- Insurers slash coverage for contractors

- High school embraces small-school format

- Better buildings can boost savings down the road