DJC.COM

October 2, 2003

Sliver towers squeeze housing into downtown

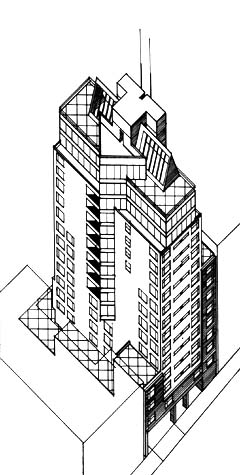

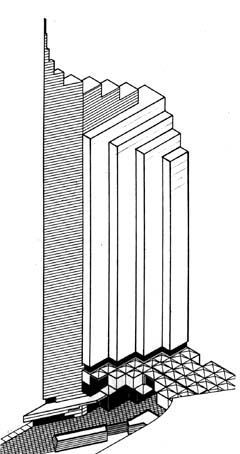

Warren Pollock & Associates

Renderings by Warren Pollock & Associates

Kauri Investments is planning this 16-story “sliver tower” apartment at Eighth Avenue and Seneca Street in downtown Seattle. The lot is 68 feet wide and 120 feet deep.

|

As our area struggles with transportation, traffic and parking problems that seem to offer the Hobson’s Choice, there is an interim solution: Live near your work.

There are sites all over the center of town that have been considered not large enough for development unless they are assembled with adjacent sites. In fact, these properties can be prime residential in-fill sites.

A 15- to 20-story residential building on a 5,000- to 10,000-square-foot site is small in scale when it is in or near our downtown skyline. They can be the under story, like small trees in a forest, that city centers need to be healthy and livable. They can be a middle step between the sidewalk and the top of the skyline.

Sliver towers

Twenty years ago, I was working on a design for a very small site in the middle of Seattle. The zoning code would allow a 33-story building but the lot area was only 6,000 square feet. At that time, downtown office buildings typically had floor areas of 20,000 to 30,000 square feet. Our intention was for the building to be mixed use with three floors of retail, 15 floors of office and residential for the top 15 floors.

While pondering if such a slim building could be built and if the market would accept such a product, I came across an article about a tall and slender residential tower in mid-town Manhattan, with two one-bedroom apartments per floor. I phoned an architect friend who was working in New York to ask if she had seen the building.

The answer was yes, and she knew of two more slender residential towers and one office building with 5,000-square-foot floors. She called these buildings “sliver towers.” The term was apparently coined because, next to the real giants of the New York skyline, these buildings looked like slivers in a wood pile.

I showed the article to my client, Tom Ferguson, and I told him that my friend said there were several such new buildings in Manhattan. To my surprise and delight he said, “Well, let’s go see them.”

|

We talked to the architects, leasing agents and tenants of the buildings and had a tour of three of them. The buildings were successful financial ventures for their owners and I felt they had a different scale and feeling than the Manhattan giants.

My client and I came back to Seattle excited about this new building type and I started to produce the design development drawings for his downtown site, but alas it was not to be. The city of Seattle bought the triangular site through the condemnation process and it is now a part of Westlake Park.

As designers often do, I mentally filed the idea away for future use.

Return of the sliver

Twenty years later, Kauri Investments asked me to study a small 8,150-square-foot lot at Eighth and Seneca as a possible site for a five-story, wood-over-concrete apartment building. The lot is zoned high-rise 240, allowing for buildings up to 160 feet tall and, in some cases, up to 240 feet tall.

When producing the envelope study of alternative schemes, I realized that a 16-story, 160-foot-tall concrete building with floor plates of 5,200 square feet at the street and 2,700 square feet at the top, and a deep garage below the street, would fit within the zoning constraints. This would qualify as a “sliver tower!”

The price of housing that I thought was outrageous in New York 20 years ago would be a bargain in the center of Seattle today. There have been several concrete-frame residential structures built in our city in the last few years and their performance in the market place is a good demonstration of the future viability of the type.

The sliver tower building type came about in New York because only small odd sites were left. All of the big sites had reached highest and best use long ago.

Seattle has reduced the allowable density for L-zoned sites several times in the last 20 years. This was partially responsible for the boom of apartment construction in the NC and C zones. The supply of these sites is now limited.

This building, which would have been one of the first sliver towers in Seattle, was never developed because the city took the land to build Westlake Park. |

Seattle’s high-rise zoned sites have been used for tall office buildings and for civic architecture, museums and concert halls, but there are a number of these properties that are not suitable for that sort of development. The change in the economics of local housing development now makes these sites potential sliver tower sites.

This is not unprecedented in Seattle. So called “skinny houses” emerged as a housing type in the 1990s in our single-family neighborhoods when the supply of lots became critically low. Sliver towers are high-rise in-fill. They are the “skinny houses” of the high-density zones.

The structural systems of these skinny towers use the elevator core for earthquake and wind load resistance rather than shear walls, which is the preferred approach for buildings up to six stories. The plumbing needs to stack because there is no space for lateral offsets, but the interior walls can be arranged differently from floor to floor so there can be a great variety of unit types in a single building.

Large units can have the full floor with windows on all sides like a house, and small units can vary in plan from floor to floor to eliminate monotony. The single-family industry has learned that tract-style development with all houses the same is not what people want or need. As we shift to a more dense living environment, we will still desire individuality and self expression in our living spaces.

It is very difficult to provide required parking on small and irregularly shaped sites because auto ramps can use most of the footprint. However these sites in the urban core are exactly the place where one can live and work and not use a car, or perhaps share a Flexcar.

When the city was originally platted, two major property owners could not agree on the proper orientation of the street grid: north-south or parallel with the waterfront. The solution was a combination of both with no coordination between them.

This created the small triangle and odd shaped lots at the haphazard intersections of the streets. They are the unintended positive consequence of that unresolved argument and they can become a significant part of our urban fabric.

With creative solutions to the parking requirements, these lots could be developed with sliver towers that would give our city a very special urban design quality which activists of the future might want to protect.

Warren Pollock has practiced architecture in Seattle for 33 years. His primary experience is in single- and multi-family housing, with an emphasis on projects with complex site conditions and environmental challenges.

Other Stories:

- Seattle calls on ‘Blue Ring’ plan for open space

- Parking lots designed to suck up storm water

- Seattle’s Green Streets ripe for modernization

- Urban sprawl causes waistline sprawl

- The surprising realities of apartment living

- Is Seattle ready to wear the Vancouver style?

- WSU forges urban development partnership

- Living over the store in funky Fremont

- The evolving role of neighborhood retail

- Tight site parking problem? Stack those cars

- Eastside tries filling an affordable housing gap

- Tax increment financing: why it isn’t working here

- Reinventing the residential high-rise

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.