DJC.COM

August 28, 2008

Spend more now to save big in the long run

Rider Levett Bucknall

Burris

|

When a school district sets out to build a new school, great effort is put forth to ensure the public is receiving both a functional and aesthetically pleasing building.

District planners meet with architects and engineers who transform their requirements and ideas into a buildable design. Each of the parts and pieces contemplated by this design is quantifiable, and from this the capital cost of the school can be determined.

However, the school that took little more than a year to build will be in operation for some 30 to 50 years. The capital cost only represents about 17 percent of the total cost of ownership.

Costs over time

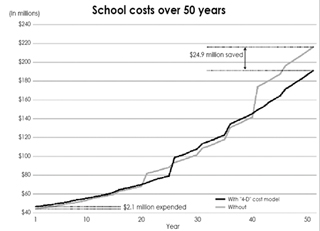

Source: Rider Levett Bucknall A "four-dimensional" cost model shows that spending an extra $2.1 million at the beginning of a school project could end up saving almost $25 million in the long run. [enlarge] |

To understand the total cost of building ownership we must develop a through-life cost model, also known as a four-dimensional cost model, or 4DCM for short. The fourth dimension, time, allows us to dynamically examine the cost of the building for each year of its life.

Contained in this model are capital costs, utility costs, operational costs, maintenance costs, scheduled component replacement costs, and furniture, fixtures and equipment costs. With a fully integrated 4DCM model, the through-life cost is updated in real time as building parameters are updated. This allows the user to compare multiple iterations of the model in order to determine the most economic scenario.

Each component of the building has a useful life and must be replaced at some point in the future. This makes the initial selection of materials and systems critical to the total cost of ownership.

For example, we frequently experience a 20-year roof specified for a school. If we assume a 50-year analysis period, that roof would require replacement at year 20 and year 40 while leaving 10 years of useful life on the table. If we were to expend more capital up front for a 25-year roof, we would only need to replace it at year 25, thus saving one replacement.

$650 million in savings

Through 4DCM optimization, Rider Levett Bucknall has shown that a minimal increase in the capital cost of the building can produce a large savings throughout the life of the building.

The graph on this page shows a sample school project. One line shows the baseline school design with no 4DCM optimization. The other line shows the cumulative cost with 4DCM optimization.

As can be seen, the lines cross back and forth until around the 40th year. At the 40th year, we see a large change where replacements must be performed in the non-optimized school to carry it through to 50 years. We can see that expending an additional $2.1 million at the beginning of the project will end up saving almost $25 million in the long run.

By implementing a 4DCM program, a school district with 3 million square feet of schools could save approximately $650 million in operational, maintenance and replacement costs over 50 years. These savings could be used in other areas in need of funding or used to offset future bond costs.

A design influence

Rider Levett Bucknall is working with the Lake Washington School District to develop a 4DCM program for its medium- and long-range bond planning. Currently the model is being populated using actual operating and maintenance data from several schools that have been recently constructed. Once the models are fully implemented they will be used to influence the design decisions for future schools.

Overseas, the use of this type of modeling is quickly becoming the norm.

The United Kingdom Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act of 2004 mandates that all new projects must contribute to sustainable development. One of the requirements of this act is that all new and refurbished buildings over 1,000 square meters must display an energy label indicating their energy efficiency and levels of carbon dioxide emissions.

The 4DCM model contains data relating to the insulating properties of the school, typical exterior temperatures for the region and occupancy loads. From this data, the heat loss of the building is determined. And from the heat loss and efficiency of the heating system, the energy use and carbon dioxide emissions of the building can be calculated.

The energy consumption will change with the percentage of window area and the thermal insulating properties of the exterior wall and roof. These parameters can be manipulated within the model to achieve efficiency goals.

Through better understanding of building-cost cycles, we are in a position to design more-enduring buildings. Instead of value engineering the building down to bare bones, the design decisions should be focused towards creating a building that will economically stand the test of time.

Christopher Burris is an associate in the Seattle office of Rider Levett Bucknall, a global property and construction consulting practice.

Other Stories:

- Can good design boost the case for school consolidation?

- Nature’s obstacles force fresh thinking in Everett

- Green goals guide UW’s Architecture Hall renovation

- What the future holds for school design

- UW building to get B-school students mingling

- Colleges expand to meet health care demand

- Northwest University answers call for nurses

- A science building that goes easy on energy

- The next generation of American schools

- 7 questions project managers should ask about BIM

- Tribal schools expand role preserving native cultures

- Mount Rainier inspires Orting Middle School design

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.