Surveys

DJC.COM

July 17, 2003

Pierce County maps where its rivers move

GeoEngineers

Reinhart

|

Wright

|

In an unaltered state, rivers expend their excess energy by eroding their banks, moving sediment and changing their position by migrating across floodplains. When rivers migrate, they erode the floodplain soils they encounter, resulting in loss of property and creating safety risks for people and businesses residing in the area.

Channel migration analysis, where geologists, geomorphologists and other river specialists map past and potential river channel locations, is a rapidly expanding management tool. Perhaps one of the best examples of the usefulness of this analysis comes from Pierce County, where the Department of Public Works and Utilities hired GeoEngineers to determine channel migration zones for lengthy sections of the Puyallup, Carbon and White rivers.

Pierce County experienced devastating floods in 1991 and 1996, during which sections of the Puyallup and Carbon river levees were overtopped, damaged or completely blown out, placing numerous homes at risk.

As a result of these and other high-flow events, the county is improving its knowledge of local water systems. The county was particularly interested in identifying the zone of possible channel migration for rivers, and areas of high and moderate migration potential.

The county plans to use this information in planning levee and infrastructure maintenance as well as identifying areas suitable for potential habitat restoration.

Photo courtesy of GeoEngineers

Analyzing channel migration of the Carbon River will be useful for land use, transportation and habitat management planning.

|

“The county’s rivers have migrated a surprising amount just in the past hundred years,” said Ken Cook, civil engineer with the county’s Water Programs Division. “We therefore felt the need to distinguish areas with high, moderate and low potential for future migration. This will allow the county to better manage existing levees, help ensure that building occurs where it is safest, and provide residents with a good understanding of probable risk.”

A river’s balance

In natural drainage systems, streams entering lower gradient reaches are seldom straight, except over short distances. Lower gradients usually encourage deposition of a portion of the sediment load in transport, which causes changes in the flow patterns, often resulting in erosion along the outside bank of channel bends.

In a state of dynamic equilibrium, erosion along the outside bank of a meander bend and deposition on the point bar at the inside bank of a meander bend both occur simultaneously, and at more or less similar rates. A result is lateral movement, or migration, of the channel across the floodplain.

The extent to which channels can migrate is highly dependent on channel gradient and the materials that make up the channel floor and banks.

In upper stream reaches where channel gradients are steepest, rivers tend to cut deep, straight channels, where bedrock formations confine the river channel in narrow, V-shaped valleys. As channel gradient decreases and the valley becomes wider, the character of the stream changes from primarily erosion to a more complex system involving deposition, bank erosion, channel widening, and development of bends and floodplains.

Sediment is also carried into the lower gradient areas, sometimes in great amounts. This sediment recruitment, when in proper balance, provides spawning and rearing substrate for fish.

River movement does not respect modern property lines. Floodplains contain our richest soil for agriculture and often represent choice areas for residential and commercial development, in Pierce County as well as the rest of the country. When a river migrates, it erodes adjacent real estate and disrupts human activities.

Historic impacts

For more than a century, people in the western states have shaped and confined rivers by building levees. The Puget Sound area is no exception. In 1907, the Washington Legislature gave county governments the authority to do flood protection work on state rivers. Since then, many levees and bulkheads have been constructed to harden stream banks and hold river channels in place. The Puyallup, Carbon and White river sections within Pierce County have been completely confined by levees and armored banks since 1965.

Although the levees reduce flooding and channel migration, they can have other unintended consequences, one being vertical entrenchment of the channel. This is where river energy that would otherwise be expended on bank erosion and channel migration is redirected to streambed erosion, or deepening of the channel.

When entrenchment occurs, the river losses connectivity with its floodplain, which can result in loss of habitat and flood water storage capacity.

Levees can also cause considerable damage to fish and other aquatic species’ habitat. As river channels deepen, they typically erode gravel beds and sand bars that fish use for spawning and rearing. Confined rivers also generally lack the balance of pool and riffle habitat and large woody debris, critical to proper fish production.

River morphology dictates the type of sediment contained within the channel, as well as habitat structure and, ultimately, the productive capacity of the river. Unlike a migrating river, a channelized river is unable to effectively recruit or retain new sediment on the streambed, or capture large wood. This severely limits the productive capacity of the aquatic habitat.

The GIS tool

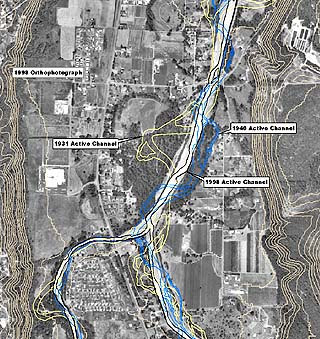

Graphic courtesy of GeoEngineers

A few of the historic channels occupied by the Puyallup and Carbon rivers. Active channel boundaries were digitized from aerial photographs dating from 1931, 1940 and 1998.

|

A crucial, but often overlooked, element of successful floodplain management and channel/habitat restoration lies in developing a clear picture of past and present channel forming processes and character.

Consequently, gaining a historical perspective of river movement over time is necessary for identifying changes in channel character and migration.

GeoEngineers’ geologists and geomorphologists searched county archives to compare and evaluate photographs and maps. In most channel migration studies, the greatest challenge lies in obtaining sufficient historical data. However, in this case, an amazing amount of information was found stored in the county’s vaults, including aerial photos dating back to 1931 and survey maps from as early as 1914.

An advancement of channel migration analysis has been the integration of geographic information system (GIS) computer programs. Photos from various years were digitized as separate data layers to a standard scale. The layers could then be overlaid to show how river channels have moved over time. Each river in the study was separated into discrete study reaches based on river morphology (i.e. channel pattern, gradient) to facilitate further evaluation of historic channel character and migration.

The GIS data layers included information such as major abandoned channels, side channels, levees, dikes and other flood-prone areas. The data generated by the channel migration zone study can be integrated with other county GIS tools, including land use plans, critical area overlays, long-range transportation planning, current road improvement projects and habitat management plans.

“With the GIS project files it is much easier for us to identify specific areas where the rivers have eroded,” Cook said. “It’s similar to viewing layers of tracing paper, one on top of another, showing where the banks of the river have been.”

The geomorphic evaluation is very important when considering levee setbacks and floodplain reconnection treatments for current river habitat management. Many counties throughout the Northwest are looking at relocating levees to give rivers greater latitude for movement, thus increasing floodplain storage, as well as hydraulic and habitat function.

“We consider the channel migration zone project to be a success,” Cook said. “It gives us a tool to identify where the erosion hazards are located. Now that we have a clearer understanding of where the rivers naturally want to flow, we can better plan future development in our county.”

Mary Ann Reinhart, LG, is a senior geomorphologist; and Wayne Wright, PWS, is a principal scientist at GeoEngineers, an environmental and geotechnical consulting firm headquartered in Redmond.

Other Stories:

- Battle over keeping dams rages on

- Be prepared with a spill management plan

- What’s your vision for Seattle’s future?

- Hat Island gets a drink from the sea

- Foss Waterway cleanup kicks into high gear

- Reclaimed water — a ‘new’ water supply

- LOTT dives into reclaimed water

- Clean air: saving our competitive advantage

- Europe points the way to sustainability

- Old maps handy for site investigations

- Planning for an environmental emergency

- Engineered logjams: salvation for salmon

- Development can be beneficial to wetlands

- Check out properties with microbial surveys

- Sculpting a park out of a brownfield

- Charting a sustainable course for the Sound

- Water rights no longer a hidden asset

- The economics of sustainability

- Laying the path for responsible education

- Squeezing more out of renewable energy

- Controlling mosquitos and the environment

- Beavers back in force in the Seattle area

- Our future: no time or resources to waste

- Port Townsend dock promotes fish habitat

- Brownfields program is here to stay

- Master Builders teaches green homebuilding

- A salmon-friendly solution on the Snake

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.