Surveys

DJC.COM

July 29, 2004

Washington tests watershed management

Golder Associates

Pitre

|

Water law in Washington is based on the Western water law doctrine of prior appropriation where "ownership" of water is considered as sacrosanct as the right to bear arms, and a water right in many cases can be exercised without regard to the effects on others.

Western water law may have been effective in encouraging settlement of the Wild West, but it is less flexible in accommodating today's resource management challenges. Watershed planning is intended to provide a sound tool for addressing these challenges.

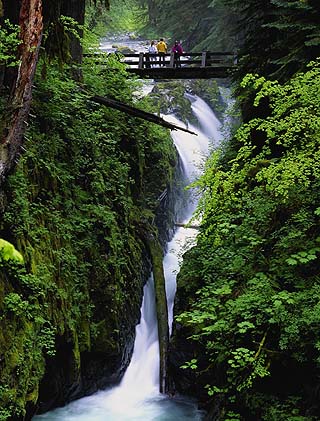

Corbis Photo

Technical assessments are being performed for the first phase of the watershed plan for the Hoh-Sol Duc region on the Olympic Peninsula. |

In April, Gov. Gary Locke joined elected officials in a joint session to approve the Nisqually Watershed Management Plan, marking the state's first watershed plan to be fully approved by the counties that share the watershed.

The Nisqually plan recommends developing a regional groundwater supply to meet future needs for drinking water and to protect freshwater habitat for salmon. It calls for local governments to consider water-supply availability when making land-use decisions, while its water assessment guidelines are expected to speed water-right decisions and protect against water pollution.

Since then, the Chehalis watershed plan has also been approved and more are expected soon.

Consensus-based plans

The foundation of watershed planning is consensus, where numerous stakeholders have veto power during final adoption of a plan that can take up to four years to complete. Therefore, working early on to develop trust and obtain consensus within the group provides the best chances of developing a substantive plan. Tackling this task takes time while the diverse group of experienced managers and lay people develop a common understanding of what is achievable and/or acceptable. Focusing on specific topics or refining information sources that are critical to plan components makes the job of coming up with a good plan easier.

Despite its roots in consensus, leadership is still required to get a useful product. Identifying a leader requires a willing candidate, resolution of internal politics and other factors. Professional consultants provide direction, in some cases.

A major benefit of the overall approach is a huge advance in communication among the stakeholders, and the development of an influential group of people in the community who are well-informed on water resource issues.

Problems and solutions

The range of water resource topics open to consideration is almost unlimited. Watershed planning legislation requires addressing water right issues, and allows addressing water quality, instream flow, storage and almost any conceivable water resources-related topic. The list is often expanded to be complete and comprehensive, with "must have" or "can't have" items from individual stakeholders, and variations of themes. But in each watershed, a narrow set of topics usually comes to the forefront. The challenge is to maintain focus.

Because time and resources for developing a plan are limited, deciding as early as possible on what type of plan is most efficient: either a broad plan that deals with as many of the issues as possible, or a focused plan that substantively develops a few key items.

The focused approach provides the opportunity to make more of a difference in selected areas.

Examples of focused efforts include: Establishing a minimum instream flow rule that protects salmon while providing water for future development in the Samish and Quilcene rivers; defining the regional water supply system in the Nisqually and Kitsap basins; establishing water banking in the Methow watershed; redoubling conservation in the form of Xeriscaping, such as in the Spokane watershed where half of all water used is lost in outdoor landscape watering; and advancing aquifer storage and recovery permitting in the Yakima Valley.

Getting it done

Planning units typically include private citizens along with agency staff, if their budgets allow. This is essentially a volunteer group and minimal financial resources are directed to administrative expenses.

Each planning unit member represents a different perspective early in the process, which avoids problems late in the game. The institutional knowledge of local resource managers and contributing state and federal agencies also helps by guiding efforts to critical topics and ensuring that the work builds on what has already been done, both historically and in ongoing parallel programs. The value of the contributions from individuals and agencies cannot be underestimated.

Planning groups often retain outside services to assist in carrying out the technical work and/or developing a plan. Many conservation districts, particularly in Eastern Washington, have ongoing natural resource programs and can economically execute the work to meet watershed objectives.

State agencies can build on work that they have already done. Federal agencies offer high-quality technical objectivity and often matching funds or free services.

Consulting companies offer the ability to staff efforts with appropriate expertise and to fulfill the objectives of the planning group without the constraints that public agencies may have. Because time is a real constraint in developing a watershed plan, consultants may provide the most realistic option for completing the work.

The range of capabilities needed in watershed planning is: communication skills; technical understanding of natural resources; familiarity with regulatory development; understanding policies; and knowledge of water supply issues.

It all comes down to balancing the pressures on our natural water resource in a technically, politically and legally defensible manner.

Hopes and expectations

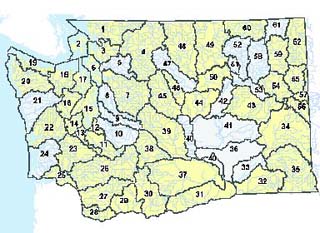

Image courtesy Golder Associates

The Watershed Management Act of 1998 provides the funding and framework for creating sustainable plans to manage water in the state's 62 watersheds. |

A basic budget of $500,000 per watershed is available, with up to an additional $300,000 for supporting studies, to develop plans over a four-year period. Up to $400,000 per watershed is available for follow-on implementation of the plans. This adds up to a possible total of $72 million, of which approximately half has been allocated so far across 45 of the 62 watersheds.

After volunteering time, money and personal commitment over four years, the stakeholders are highly vested in the development of substantive plans. The plans may be successful if the recommendations for resource management are followed through. This will require specific, tangible recommendations with the commitment of participants.

The funding and logistical support from the Department of Ecology for this program has been unwavering since its inception, and local planning efforts have been allowed great freedom in choosing their approaches. This allows the greatest level of creativity and innovation, such as using reclaimed water for streamflow augmentation and mitigation of water right impacts in the Kitsap Peninsula.

The success of the plans will determine the level of continued support from the state, the freedom and discretion of local groups to deal with watershed planning in their manner of choosing, and the funding for implementation.

Chris Pitre is part of a group of technical and policy watershed planning professionals at Golder Associates who have been involved in planning 16 Washington watersheds.

Other Stories:

- Conditional closures — another cleanup remedy

- Guy Battle: design and build to suit your climate

- Todd Pacific halts a dirty waterfront legacy

- Going green? Try calling on your contractor

- Emerald City must fight to stay green

- Seattle prepares to ‘re-green' 2,500 acres

- Washington's new paint law gets the lead out

- Putting a price tag on nature

- South Lake Union: a model for sustainability

- Contractor finds silver at new headquarters

- Government finds gold at Sea-Tac Airport

- Quick Duwamish cleanup begins with teamwork

- 2004: A great year for the local environment

- Getting to compliance with a systems approach

- Don't let your site be taken to the cleaners

- Salmon get a boost from technology

- Low-impact development comes to Pierce County

- Energy Star label now ready for homes

- Improving traffic flow for fish, people

- Troubling times for Hood Canal's waters

- Utilities to study energy coming into homes

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.