DJC.COM

November 19, 2009

21st-century waterfronts: What makes them work?

Surdyke

|

With a major slowdown under way in international trade, our once-thriving industrial waterfronts and are now at a crossroads.

Beginning with the national decline of industrial land in the mid-20th century, many cities have been left with vast tracts of abandoned and contaminated waterfronts and upland properties. Today, however, the explosive population growth in urban regions has ushered in a new era of economic development, environmental awareness and social responsibility.

Consequently, cities are now reevaluating and rediscovering their waterfronts as diverse and vital resources, where there are also many competing interests. The 21st-century transformation of the urban waterfront includes the introduction of new mixed uses, including recreational, residential, commercial and educational facilities.

Here in the Pacific Northwest, and particularly in Seattle, there has been an age-old conflict that has seemingly come to a head: Die-hard industrial advocates have staunchly defended the existing industrial uses against the invasion of “non-compatible” uses such as residential, commercial, recreation, bike trails and other non-water-dependent uses.

Image courtesy of Dockside Green

An active shipyard will sit beside a 1.3 million-square-foot neighborhood at Dockside Green in Victoria, B.C. |

Our region does support and depend on the success of our fishing, shipping and other water-dependent industries, which make our ports among the most successful in the nation. At the same time, however, we are also realizing the critical importance of our waterfronts as vital links in the damaged ecosystem of Puget Sound. Decades of unregulated contamination have resulted in our region’s unfortunate claim to some of the most contaminated urban waterways in the nation.

Efforts to support traditional, water-dependent industry while restoring fragile waterfront ecosystems and accommodating urban growth have resulted in unique new models for mixed-use development on the waterfront.

In contrast to the retail and tourist-oriented waterfronts that proliferate on the East Coast, cities here in the Pacific Northwest are striving to maintain a true “sense of place” that preserves and encourages traditional water-dependent industries of the working waterfront, while at the same time introducing a broader mix of uses and new standards for shoreline restoration and overall sustainability.

Dockside Green

Photo courtesy of Dockside Green

The 93-unit Synergy condominiums at Dockside Green received a LEED platinum certification. The complex has four buildings over underground parking. |

Dockside Green in Victoria, B.C., is an excellent example of sustainable public-private development. From the city that for decades has dumped untreated sewage into the Strait of Juan de Fuca, now comes the world’s first LEED platinum mixed-use community.

Dockside Green is a $1.14 billion project that will ultimately include 1.3 million square feet of residential, commercial, retail and industrial uses. The 15-acre project, built on a former underutilized industrial site, is situated right next to thriving shipyard. The successful melding of new residential, commercial, retail, maritime and light-industrial uses with an existing shipyard is quite a contrast to the notion that such uses are non-compatible and have no place near the working waterfront.

In addition to processing its own sewage on site, Dockside Green features its own biomass heating plant, which will be fueled by wood waste. Centralized water boilers connected with the heating plant will in turn heat the entire community.

Rain water will be recycled and “black water” will be processed to provide water for toilets and irrigation. Water retention basins in the form of open streams and waterfalls run throughout the project.

The community features both affordable and market rate housing. All buildings within the master development will feature extensive recycling programs and are to be built using local, sustainable and recycled materials.

As part of the agreement with the city of Victoria, the developer’s goal is to divert 95 percent of the construction waste from ending up in a landfill. The project also includes extensive drought-resistant landscaping, and features open space and an extension of the waterfront bike trail.

With a balance of maintaining its working waterfront while providing the highest standard in environmentally responsible mixed-use urban development, Dockside Green has set the new standard in our region for urban waterfront redevelopment.

Foss Waterway

Photo by Chuck Lysen

With open space, shoreline habitat, offices, housing and water-dependent uses, Foss Waterway offers a successful model for waterfront development. The Museum of Glass, completed in 2002, is shown above. |

Tacoma’s Foss Waterway is perhaps the most complete and comprehensive new mixed-use waterfront in Washington. To date, there has been over $375 million in private development and $105 million in public funds invested (primarily for the cleanup of the waterway and for open space).

The former Burlington Northern property, purchased by the city of Tacoma, has been strategically master-planned and developed by the Foss Waterway Development Authority, a public development agency similar to the Portland Development Authority.

The heart of the Foss Waterway is the public esplanade, a 1.5-mile long seawall and pedestrian walkway that connects the new developments with a network of open spaces and pocket parks. Inspired by the seawall in Vancouver, B.C., and Portland’s Riverplace, the Foss Waterway esplanade features unobstructed views and access to the restored shoreline.

The Foss Waterway Development Authority worked in conjunction with the Port of Tacoma, the Puyallup Tribe and the state Department of Ecology to ensure that shoreline habitat restoration was in keeping with the highest standards and the long-term vision for the health of Tacoma’s urban waterways. Improvements include recreating urban saltwater and estuary marshland, designed to provide habitat for fish, marine mammals and birds.

With acres of new open space and restored shoreline habitat nestled among hundreds of new multifamily housing units, offices, restaurants, new marinas, existing water-dependent uses and the signature Museum of Glass, the Foss Waterway stands as an inspiring and successful model for balanced and sustainable waterfront development.

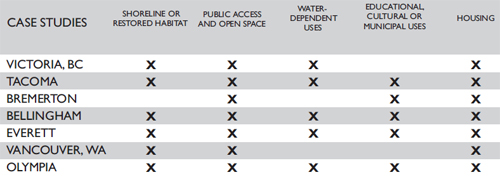

5 common features

Major waterfront projects in the region have common features that guide land use policies and development. |

Along with Victoria and Tacoma, waterfront developments are under way in the cities of Bremerton, Bellingham, Olympia, Everett and Vancouver, Wash. In these new regional waterfront developments, there are five common features that serve to guide land-use policies and development:

• Sustainability: Victoria, Bellingham and Olympia’s major waterfront developments all have LEED certification requirements. Dockside Green is LEED platinum. Foss Waterway has accomplished extensive shoreline habitat restoration by working in conjunction with the Port of Tacoma and the Department of Ecology.

• Water-dependent uses: The preservation and/or expansion of water-dependent commercial and industrial uses was considered important. However, in some of the cities above, there are programs for removing low-density, non-water-dependent uses such as light-industrial and storage warehouses.

• Public access: Residents in Bellingham overwhelmingly cited the importance for better public access and open space on the waterfront. Each of the cities above made this a priority.

• Educational, cultural or municipal uses: The redevelopment and restoration of the urban waterfront can provide a showcase of educational opportunities. Tacoma’s Urban Waters research center is under construction on Foss Waterway. In Bellingham, Western Washington University is planning a waterfront campus for the Huxley College of the Environment in a former Georgia Pacific Mill building.

• Housing and commercial uses: All of the cities above have incorporated residential and mixed-use zoning into the upland areas of the urban waterfront. Often, the primary reasons cited for introducing these uses include the need to help pay for extensive environmental remediation and shoreline enhancement, and the desire to make the waterfront a thriving, safe and round-the-clock neighborhood.

Subsidizing certain uses

The concept of “cross-subsidizing” less profitable water-dependent uses with more profitable, higher-density non-water-dependent uses is a means of addressing a major underlying economic reality hindering the environmental restoration of the waterfront. Simply put, remediation of contaminated shorelines can cost tens of millions of dollars.

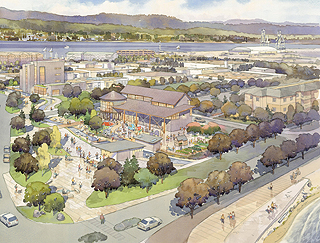

Image courtesy Mike Kowalski

Olympia’s East Bay is one of a number of major waterfront developments under way in the Pacific Northwest. The Hands On Children’s Museum, shown here, is slated to open in the fall of 2011. |

It is difficult for any municipality or port to justify spending such sums of money on efforts that only provide for maintaining existing water-dependent uses. For cities whose combined goals are both environmental remediation and the preservation of water-dependent uses, the need to offset these costs are often accomplished through the introduction of higher-density, non-water-dependent uses. Without the possibility of substantially increased revenue, it is unlikely that sufficient remediation or shoreline habitat restoration will occur.

From an economic standpoint, cross-subsidizing land uses makes sense as it preserves water-dependent uses that may produce lower yields while generating higher income from non-water-dependent uses.

The higher income generated can then be used to offset money spent on environmental remediation, site preparation and habitat restoration. From the sustainability perspective, the introduction of a greater mix of uses on the urban waterfront adheres to smart-growth principles by making more efficient use of a precious and rare resource.

Not only does this approach ensure a cleaner and safer working waterfront environment, but it also helps contribute to trip reduction due to the close proximity of jobs, housing and services.

In light of this, the “no action” alternative — where municipalities fail to reevaluate the waterfront in favor of land banking or simply letting underutilized waterfront sites sit vacant for “future use” — seems like an outdated option, given the convergence of land-use economics, environmental goals, population growth, and the need to provide job opportunities and reverse years of waterfront contamination.

Fortunately, many of the cities in our region have already taken a bold step forward and are redefining the many roles of the urban waterfront.

Scott Surdyke is an urban development consultant and project manager. He has worked on mixed-use developments in the Seattle area for over 12 years.

Other Stories:

- Bellingham embarking on ambitious waterfront plan

- Magnolia Bridge complicates pier project

- Placid park belies a major engineering effort

- Bellevue reconnecting with its waterfront

- Planning a shoreline project? Win over the public first

- Kennewick island lighthouse a beacon for downtown

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.