![[Protecting the Environment]](envirocover.gif)

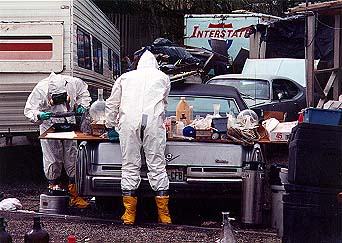

METH LAB: OVERNIGHT ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARD

BY LUCY BODILLY Methamphetamine does more than boost the crime rate, create drug addicts and turn normal lives into nightmares. Its manufacturing process presents an immediate environmental hazard. In fact, the state Department of Ecology spends hundreds of thousands of dollars each year cleaning up the sites where meth is "cooked." Just to remove the debris and ship it to a waste dump costs at least $3,000. Any remediation is extra. And the state has cleaned up 60 sites so far this year just in the Southwest region, from Olympia south to Vancouver and the Olympic Peninsula. Most of the environmental problems arise when the cooking is actually taking place. Meth is made by taking ephedrine or super-ephedrine tablets, found in Sudafed and other decongestants, and heating them until the ephedrine is highly concentrated. It takes thousands of common ephedrine tablets to make one pound of meth, according to Aaron Alderson, head of meth lab cleanups at Olympus Environmental in Auburn, the company that holds the

Though several other remediation companies have contracts for meth lab cleanups, Olympus is chosen most often, because it has offices located throughout the state. "We are a full-service lab. Back in 1987 we wanted to get involved in emergency response work with the DOE and this the end result," Alderson said. The company has about 100 employees with offices in Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Montana. While the ephedrine itself is not that harmful, the chemicals used to cook it are. Some common chemicals are red phosphorus, ether, mercury and hidrotic acid, available at any hardware store. The ephedrine is the hardest chemical to obtain. Though it is readily available in decongestants, the low concentration makes it difficult to process efficiently. The average ephedrine pill is just 25 milligrams, and it is concentrated many times through the cooking process. A pound of meth eventually will sell for between $5,000 and $7,000 on the street, said Sgt. Gary Sundt of the Washington State Patrol. A basic cleanup calls for sampling the contents of containers left on site, consolidating identical chemicals into the same drums, and shipping it to the landfill. More complicated cases require testing interior finishes, septic systems and wells. "Usually we don't have to do that, but some cooks make their own drains and dump the chemicals out in the yard. Then it could cause groundwater contamination," said Brett Manning, a biologist at the state DOE in charge of Southwest region cleanups. The Washington State Patrol also takes its own samples and holds them as evidence. It stores small vials of the samples in sealed paint cans filled with kitty litter, to ensure absorption, should the chemical spill in the paint can, Sundt said. After fingerprinting containers and glassware, the site is photographed, and the cleanup team can move in. Just knowing a site was a meth lab tells nothing about the degree of contamination, according to Jeff Burgess, M.D., M.H.P., a toxologist at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle. "You can't assume what will be contaminated, just because you know that the site was a meth lab," he said. "If there was a fire or an explosion, there will be contamination all over. Or if the cook was messy . . . If the chemicals were stored in one room, and the cooking was done in another room and the drying done in another room, there will be more contamination," he said. The state DOE mandates that the chemical cleanup must take place, but it is up to the county health department to order further testing and to force the owner to clean up interior or groundwater contamination, Manning said. Interior contamination happens when vapors created in the cooking process are absorbed by the drywall or carpeting. "Usually there is no widespread hazard, but it is an emergency because we don't want a bunch of kids to go into the site and start playing with the stuff," Manning said. "Besides only the state would make sure that the cleanup was done correctly." "It's the same procedure as any other site where you have a bunch of unknown chemicals, said Alderson." Though contamination is not usually found in the building materials or groundwater, chemicals left on the site can cause problems for everyone who visits there after a cook, Burgess said. "Basically we have three types of chemicals: corrosives which can burn or irritate the skin and mucous membranes and solvents which can cause headaches and dizziness. The actual meth does not cause problems unless the victim ingests it." Some of the irritation can be caused when chemical residue becomes airborne, during vacuuming, for instance. Sites vary from rental property to vans to state forest lands. The owner is technically responsible for the cleanup, but is rarely charged for the costs, Manning said. "Unless we can prove the owner knew about the lab, we don't charge them. The state just ends up paying the bill." Similarly, property owners cannot be prosecuted on criminal charges unless they know that meth is being cooked on their property. The cooks themselves are the most apt to be hurt by environmental contamination. But a number of chemicals have been taken off the market to stem meth manufacture, and their substitutes have less effect on the environment. When meth was first manufactured in the 1970s, the recipe called for lots of heavy metals. Contamination throughout the site was more common. The next cooking method used lots of solvents and caustic material, which would also be harmful, but was more likely to evaporate before it caused much trouble. "One process calls for the cook to spray ether onto the oil that rises to the top at the end of cooking process. The ether dries out the oil and what is left is meth," Alderson explained. "One guy didn't want to wait for the ether to work, so he put the whole thing into the oven. He got caught because of the resulting explosion," Alderson said. The newest method, called the Nazi method, calls for a "cold cook" using liquid ammonia, dry ice and acetone. Cooking is started by running an electric charge from a lithium battery through the mixture. (For more information surf the Internet). "Though the ammonia can be a problem, this is much better for the environment because everything evaporates so quickly." Alderson said. But, it is much harder on law enforcement agencies. The method can yield a batch of meth in less than an hour, as opposed to several days with the older methods, making it much harder to catch the criminals. A cleanup where the newer method is used rarely requires more than the removal of debris. "What we usually end up with is 15 to 20 containers of unknown chemicals," Alderson said. He cautioned that none of the material is ever stored at company offices, but is sent directly to a landfill. "Cooks are very resourceful and we don't want people to think they can get chemicals here," Alderson explained. The Nazi method also takes up much less space, minimizing the geographic area of the contamination, unless the lab is mobile. "We sometimes find labs in the backs of cars, usually Camaros, which get pulled over for other reasons," Manning said. Meth labs account for well over 90 percent of the drug lab cleanups in the state Burgess said. Other synthetic drugs, such as LSD, are much more dangerous to manufacture and are limited to a small number of labs in the country. |

Return to Protecting the Environment top page

Return to Protecting the Environment top pageCopyright © 1996 Seattle Daily Journal of Commerce.