Surveys

DJC.COM

November 15, 2001

Preserving a church gets personal

ABS Consulting/EQE

Ayres |

Scaffolds and brick piles are common sights around downtown Seattle since the Nisqually earthquake hit the Puget Sound on Feb. 28. Each restoration reveals a story of the past and sets a marker for future generations.

Trinity Parish Episcopal Church is one such haven of life history, proudly claiming the corner of Eighth Avenue and James Street since 1892 after the original 1865 structure at Third Avenue and Jefferson Street was consumed in the Great Fire of 1889.

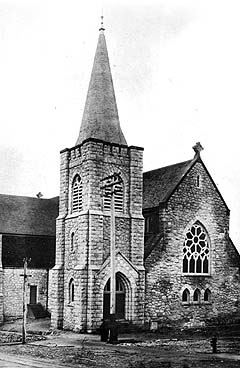

In 1902, Trinity endured yet another fire. Architect John Graham Sr. led the design effort that salvaged much of the sanctuary’s exterior masonry construction, expanded its size and added the classic bell tower and spire.

. Photo courtesy of Mark Gralia/Trinity Parish Trinity Parish Episcopal Church in 1903, a year after fire consumed much of its interior |

The church continued its work, just up the hill from downtown in what was once known as the Streetcar Suburb.

With the streetcar came people, with people came change — hospitals were erected, apartments built, wars fought — yet still it stood, ever adapting to a changing community’s needs.

Today, surrounded by fencing and scaffolding, the sanctuary is yellow-tagged until the work currently underway can make it a safe haven again.

Trinity parishioners convene for worship just steps away in the Parish Hall, overlooking a quaint cross-shaped courtyard. This portion of the church is a 1930’s masonry addition housing offices, meeting areas and the Northwest Harvest food bank program. It sustained only minor structural damage.

Survivor

Having survived the 1949 and 1965 earthquakes, the Rev. Paul Collins says the sanctuary’s damage from the Nisqually earthquake came as a surprise. “At first we didn’t think it was that bad,” he says.

|

Ray Durst, Trinity’s maintenance manager, performed a preliminary walk-through to document visible damage and chronicle the church’s experience.

The quake hit on Ash Wednesday, a day packed with services. It so happened that the event occurred between services and Collins was the only person in the chapel at the time. He was standing by the baptismal font and rather than run to the front entrance for safety, he stayed put, likely saving him from injury.

The EQE Structural Engineers Division of ABS Consulting was called in the day after to assess earthquake damage and quickly began formulating repairs that would make the church safe for its parishioners and the public.

As senior project manager John Riley recalls, the bell tower sustained the most obvious damage as he approached Trinity because significant portions of stone had fallen off. He believes that had Collins exited through the chapel’s main entry, he could have been crushed by falling stones.

Riley notes the three major areas of earthquake damage: 1) the upper stone transept walls had pulled away, with light penetrating through a corner of the sanctuary; 2) a brick chimney partially collapsed and penetrated the roof; and 3) some large stones fell from the bell tower through the roof at the main entry to the sanctuary.

A significant seismic upgrade was in store if this church building was to be around for generations to come. Simply repairing the structure would not be enough.

The job

| Project team: |

|

Architect: Bassetti Architects Structural engineer: ABS Consulting/EQE Mechanical engineer: deMontigny Engineers Electrical engineer: Travis, Fitzmaurice & Associates Acoustical: Michael R. Yantis Associates Hazardous materials: Prezant Associates Emergency repair contractor: Bayley Construction Masonry subcontractor: Keystone Masonry |

In the beginning, the project goal was to bring the building into life safety compliance. Bayley Construction was brought in to erect emergency shoring and to put up fencing that would protect the public and the church from some of the worst areas.

Work was underway within a week, including exploration of the sanctuary walls, shoring up and bracing the bell tower, and temporarily patching the roof holes. But more extensive seismic retrofit measures were necessary, like applying shotcrete to the interior, and Riley knew that those efforts without an architect on board would have a huge impact on interior finishes. He recommended the church hire an architect.

Through a formal RFP process, Trinity selected Bassetti Architects.

With Bassetti on board, facilities programming and a comprehensive look at preservation were integrated into the project. As Bassetti principal Marilyn Brockman explains, the first goal was to look at the church’s overall program needs and see how to fit that “into the shell of a historic fabric.”

Riley concurs, noting that by moving into a traditional design process, it gave funding a chance to catch up, which includes a possible FEMA grant, loans and donations. This was no longer an urgent earthquake repair process, but rather a preservation and upgrade effort.

Bassetti began work with Trinity to look at design options, such as mechanical, lighting and electrical improvements, as well as architectural functional upgrades. As Brockman explains, they accomplished this task by holding charettes (or workshops) with church members to ascertain what kinds of programs the church campus needed to provide, as well as the future use of the sanctuary to focus the dollars in the right direction.

It became apparent that issues of access were important, including handicap access, evening security and space for educational programs. Preserving the interior architectural integrity of the building was also key, which meant the goal would be to hide the seismic upgrade as much as possible. This was the time to really think about how to add centuries of life to the sanctuary.

Historic preservation

Preserving the church’s historic beauty is the greatest challenge; one that Brockman says is mainly due to the complexity of the seismic upgrade. Many improvements can be hidden, such as lighting, ventilation and acoustics, but because the architectural features are directly tied to the exterior stone and backup brick walls, an inexpensive architectural preservation remedy doesn’t exist.

| Seismic upgrade at a glance |

|

|

“In a building like this, there’s no easy way to splice a new element into it,” says Brockman.

Brockman’s goal as part of the design team is to find ways to conceal the enhancements and maintain the grace of the original structure.

That grace comes from such relics as pre-World War I German stained glass and an early 1900s marble altar and backdrop purchased in New York in 1914. The altar was re-caulked just six months prior to Nisqually and otherwise could have ended up in pieces. Unbelievably, all the stained glass remained intact despite falling bricks and stones from the chimney and bell tower.

The most significant issue being addressed by the seismic upgrade, as Riley explains, is the separation of the sanctuary’s massive and tall exterior masonry walls (approximately 2-foot thick sandstone and brick) from the wood-framed upper walls and roof of the church.

The design team agrees that the only way to complete the seismic upgrade without impacting the interior finishes is to remove select architectural elements (like the wall finishes, some stained glass windows and pews), perform the repair/upgrade and put everything back in its place.

For Riley, it’s a fascinating project as an engineer dealing with old sandstone and brick materials that challenge the retrofit process because such heavy materials don’t fare well in earthquakes.

“It becomes about how you tie it all together to make the building more durable against seismic forces,” says Riley.

On an architectural level, working with historic buildings is like a history lesson for Brockman, both in seeing past designers’ creations, as well as building on that original history to preserve the building for future generations.

Brockman and Collins agree that historical buildings like Trinity Parish Episcopal Church are more than cultural legacies, they symbolize the spirituality of a long-standing congregation.

“This congregation is very attached to this building and its history, but also its sacredness,” says Collins.

For Riley and Brockman, the project is ultimately about the people. Their work as engineer and architect is to bring the parishioners back into their home. A place where, as Collins notes, is filled with people’s personal histories. Many parishioners have family members buried in the courtyard and have had generations of weddings and baptisms under the same roof.

Riley wants to know that at the end of the day, the parishioners can have a sense of home when they finally get to worship again in the place that has been so familiar for the last century.

“People live and die in these buildings. I want the congregation to feel safe, secure and comfortable; which is how you should feel when you go to church. Worshiping is a very personal and emotional experience. I want them to be able to say, ‘We did the right thing in 2001 by renovating this historical space that will last for generations to come.’ “

The design team for Trinity Parish Episcopal Church also includes architect Don Brubeck of Bassetti Architects and engineer Graham Browne of ABS Consulting, EQE Structural Engineers Division.

Heather Ayres is the marketing coordinator at ABS Consulting, EQE Structural Engineers Division.

Other Stories:

- A peek into the architectural process

- Getting a project off the ground

- Head and shoulders above Sea-Tac

- High-rise homes with all the right stuff

- So you’re in it for the money

- What you need to know about your competitors

- Thea’s Landing: Downtown Tacoma’s new urban housing

- Rebirth of a Commencement Bay chateau

- New museum will have Tacomans glassy-eyed

- Beyond the urban core: Learning from the pioneers

- Achieving design certainty through collaboration

- Controlling stormwater the natural way

- Orchestrating Belltown’s rebirth

- Mechanical moxie: Innovations at the new Opera House

- Small housing: A Northwest mini-trend

- Delivering the goods in a tight economy

- Don’t overlook moisture — the silent threat

- Designing a one-building ‘city’ on a Norwegian fjord

- The changing face of retail design

- Preserving affordable housing by design

- A cap over troubled waters

- Hospitality industry draws on refuge and prospect

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.