DJC.COM

October 2, 2003

Seattle’s Green Streets ripe for modernization

Magnusson Klemencic Associates

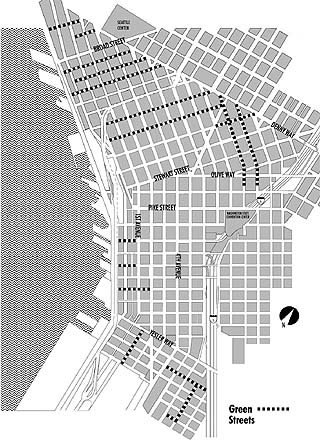

Graphic courtesy of Magnusson Klemencic Associates

Designated Green Streets for the downtown Seattle zone.

|

The goals of the city of Seattle’s Green Streets program are reasonably straightforward, but the process of implementation can seem circuitous to even the most dedicated participant.

Developing new projects along a designated Green Street involves narrowing the existing roadway to reduce the amount of area devoted to traffic and parking and to increase the amount of “open” space for sidewalks and landscaping. Yet, while city code requires land use officials to enforce Green Street guidelines, city transportation officials are understandably resistant to major changes along a perfectly good street.

Those on the development side just want to design and build a streetscape and get on with it. They have historically felt caught in the middle.

However, a wave of recently completed projects has shown that the Green Streets process can be successfully navigated, giving the program new momentum and ushering in a new generation of “voluntary” Green Streets. Upcoming projects are raising the bar on Green Street components, increasing the potential benefits to both the community and environment.

The basics

Seattle’s Green Streets program celebrates its 10th anniversary in November. The program, enacted as a land use code initiative, designates certain urban corridors as Green Streets for the purpose of improving the pedestrian environment.

The Seattle Municipal Code defines a “Green Street” as “...a street right-of-way which is part of the street circulation pattern, that through a variety of treatments, such as sidewalk widening, landscaping, traffic calming, and pedestrian-oriented features, is enhanced for pedestrian circulation and open space use.” In essence, narrow the roadway by moving the curb out and fill the captured space with sidewalks and greenery.

Green Streets are designated through City Council action. Once designated, any future improvements to the Green Street must be carried out according to guidelines adopted in 1993. The land use code provides incentives for developing projects along designated Green Streets in the form of floor area bonuses akin to those given for other public benefits, such as weather protection, hill climb assist, etc.

The paradox

Implementing a Green Street improvement puts one squarely in the middle of two very different city departments: the Seattle Department of Construction and Land Use (DCLU), arbiter of the land use code, and the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT), authority over the public street right of way.

DCLU’s goal is to narrow the roadway on a designated Green Street as much as possible in order to create open space opportunities, while SDOT is concerned that narrower traffic lanes mean the loss of roadway safety, capacity and function.

This paradox was recognized during the adoption of the Green Street program, in that both agencies collaborated on crafting the Green Streets design guidelines and both agencies are involved in the approvals process.

However, it’s a pretty good bet that the departmental paradox will manifest itself in some form on every Green Streets project.

This is not because of some interdepartmental squabble. In fact, both agencies are sensitive to the Green Streets’ mission and are helpful in moving approvals along. However, the design guidelines merely outline desired Green Street elements and refer to a somewhat out-of-date permitting flowchart. It befalls each individual project owner to re-engineer the street frontage in question (and typically at least one block in each direction) and to negotiate their way to a consensus between DCLU and SDOT over the balance of appropriate open space and prudent street function.

Addressing the paradox

For development projects without Green Streets, SDOT is the sole agency involved in review of proposed street frontage improvements. These improvements are typically limited to projects such as replacing sidewalks and adding street trees, but all within the existing sidewalk area. SDOT reviews are relatively painless, and the one-stop-shop makes their timeframes reasonably predictable.

Since Green Streets have the added complexity of checking for compliance with the land use code, DCLU reviews are required as well. Designing to both sides of the Green Street paradox has been the key to recent implementation successes.

Understanding both agencies’ issues with a given frontage and following a collaborative and methodical approach to conceptual approval will ensure that roadway layout can be approved as early as possible in the design process. Once that is set, interrelated items such as sidewalk layout, sidewalk grading, building door entries and floor elevations can be determined.

The first step is ascertaining if you are on a designated Green Street by checking the neighborhood plan for the area in which your project is located. Then, lay out proposed Green Street elements that meet current DCLU and SDOT guidelines and goals. Next, meet with both agencies to obtain their buy-in, and, lastly, finalize the design.

The key is not to get too far along without seeking both agencies’ input.

Magnusson Klemencic Associates has been involved with this approach in carrying out several recent projects:

- Touchstone’s Fifth and Bell project in Belltown added 1,820 square feet (121 percent) more open space to Bell Street.

- Harbor Properties’ Alcyone project in the Cascade neighborhood added 1,500 square feet (50 percent) more open space to Minor Avenue.

- Touchstone’s Ninth and Stewart project in the Denny Triangle added 1,450 square feet (32 percent) more open space to Ninth Avenue.

A larger work in progress includes the Vulcan/Milliken 2200 Westlake development with five street frontages, two of which are designated Green Streets. The project will add 6,550 square feet (74 percent) more open space to Ninth and Terry avenues (the designated Green Streets) and 1,500 square feet (50 percent) more open space to Lenora Street as voluntary greening.

All of these projects will add significantly more green space between the curb and sidewalk than a conventional project, with the added benefit to the city of controlling stormwater runoff. Just as importantly, the projects break up the gray monotony of the standard urban corridors.

Future trends

Now that the public can see the aesthetic, vibrant benefits of Green Streets firsthand, and owners are experiencing the increased appeal to their property, design teams are looking for ways to voluntarily introduce these design elements into their frontages (i.e., along non-designated streets). This is especially true for streets with low-volume traffic and high pedestrian activity.

Curb bulbs at intersections and mid-block, plantings at the base of street trees, and unique sidewalk paving are becoming common elements of today’s proposed street designs. For these voluntary Green Streets, the process described above must be augmented to include selling DCLU and SDOT on the suitability of Green Street design for these non-designated streets.

Fortunately, the agencies are quite open to the discussion. For example, the Schnitzer/Vulcan Interurban Exchange 3 project, under construction on Terry Avenue in South Lake Union, will sport curb bulbs and pedestrian-scale lighting as the first project in a six-block corridor of voluntary greening.

Voluntary projects on the boards are also pushing the envelope beyond the Green Street goals of creating more landscaping and sidewalk along a frontage. Excess space is being eyed for things such as denser vegetation for slowing down rainwater, water quality swales for stormwater cleansing, incorporating water as a site feature for pedestrian enjoyment, and urban P-patches — creating a synthesis of Green Streets and SEA Streets, a program that helps protect salmon.

If this trend continues, Seattle’s 10-year-old Green Street program — innovative in its time — may catch up with programs of other municipalities around the country that have advanced to new levels. Such programs have expanded the term “Green Street” to mean enhancing the functions that streets perform in the city’s urban sustainability strategies: cleansing runoff destined for fish habitat, reducing urban heat-island effect and improving air quality.

In fact, the goal of Green Streets in Portland is, “streets that are designed to protect, and attempt to mimic, the natural hydrology of an area...” Portland devotes three volumes of new detailed design guidelines for its Green Streets program — a far cry from Seattle’s 14 pages of 10-year-old information.

In some respects, Seattle was ahead of its time in adopting a Green Street program years before the international sustainability craze caught on. However, we should consider upgrading our program and begin integrating other sustainable strategies into the mix. Of course, this will bring a third party to the table, Seattle Public Utilities, the authority of surface water management in the public right-of-way. Hmm...

Drew Gangnes is director of civil engineering at Magnusson Klemencic Associates. His urban civil engineering focus is on getting the most sustainable results out of the improvements required of a project.

Other Stories:

- Seattle calls on ‘Blue Ring’ plan for open space

- Parking lots designed to suck up storm water

- Urban sprawl causes waistline sprawl

- Sliver towers squeeze housing into downtown

- The surprising realities of apartment living

- Is Seattle ready to wear the Vancouver style?

- WSU forges urban development partnership

- Living over the store in funky Fremont

- The evolving role of neighborhood retail

- Tight site parking problem? Stack those cars

- Eastside tries filling an affordable housing gap

- Tax increment financing: why it isn’t working here

- Reinventing the residential high-rise

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.