|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Construction

| |

|

April 14, 2016

How much do you know about the new 520 bridge?

Washington State Department of Transportation

Peer

|

Fifty thousand people walked, ran or biked across the new state Route 520 floating bridge earlier this month during the span’s grand opening celebration.

The event gave the public the chance to experience the bridge, by foot power and pedal power, before it opened to vehicles on April 11. The celebration also allowed visitors to learn something about the science, technology, engineering and math behind construction of the world’s longest floating bridge.

A lot of questions were asked, and answered, during the bridge festivities. Here are some of the most frequent questions about the new World’s Longest Floating Bridge.

Why do we have floating bridges on Lake Washington?

Geology and topography are the main reasons Lake Washington doesn’t have suspension bridges a la the Tacoma Narrows or Golden Gate bridges.

Lake Washington is deep, with depths exceeding 200 feet. What’s more, beneath the lake’s floor lie thick layers — another 200 feet or so — of soft silt and mousse-like glacial sediment called diatomaceous soil. Because of the lake’s deep waters and gooey bottom, the foundations for a fixed bridge’s support towers would have to be extremely deep to reach dense soils.

What keeps a floating bridge afloat?

A floating bridge is held above the surface by pontoons — basically large, watertight concrete boxes. For the SR 520 floating bridge, resting atop its 77 pontoons are 772 concrete columns, 331 concrete girders, and 776 precast roadway deck sections.

Each of the bridge’s 21 biggest pontoons is longer than a football field, as tall as a three-story building, and as heavy as 1,600 African bull elephants (about 22 million pounds). They are the heaviest, widest, deepest and longest floating-bridge pontoons ever built.

The pontoons’ many individual cells have electronic sensors for detecting a leak and sending an alarm to WSDOT offices in Medina and Shoreline.

Where were the pontoons constructed?

WSDOT contractors built all of the bridge’s jumbo pontoons along Grays Harbor in Aberdeen. Most of the smaller, “supplemental stability” pontoons, which provide added buoyancy and stability, were built along Commencement Bay in Tacoma.

What keeps a floating bridge from floating away?

The new SR 520 bridge is, in a sense, a 1.5-mile-long concrete boat. Left unsecured, it could indeed float away.

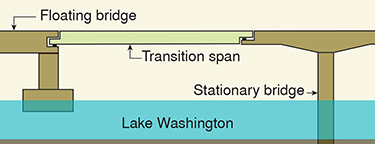

Part of what keeps the bridge in place is hinged connections, at the east and west ends, to fixed bridges — the land-linking “approach” bridges. The floating bridge’s primary fasteners, though, are 58 huge, concrete anchors. The largest ones weigh nearly 600 tons when filled with ballast rock.

Steel cables, more than 3 inches thick and up to 1,000 feet long, cinch the bridge’s pontoons to the anchors.

Are earthquakes a threat to the floating bridge?

Not really. Earthquakes pose more of a risk to fixed bridges with support piers embedded in the ground.

High winds and strong waves are the biggest threat to floating bridges. Wind-fueled waves can cause bridge pontoons to bend, heave and twist. The movement creates stress in the pontoons and their anchor system.

Past storms sheared off components on the old SR 520 floating bridge and caused pontoon cracks and leaks that required significant maintenance and retrofits.

Is the new floating bridge stronger than the old one?

Yes, its design and construction, with bigger and stronger pontoons, heavier anchors and thicker anchor cables, combine to make it more resistant to storms.

The new bridge is built to withstand winds up to 89 mph — a once-in-a-century storm. In contrast, the old bridge was built to handle 59-mph winds, and frequently had to be closed when sustained winds topped 50 mph.

Will waves still wash over cars on the new bridge during windstorms?

No. At the new floating bridge’s low point, the roadway surface is 20 feet above the lake’s surface. By comparison, the old bridge’s roadway is only about 6 feet above the lake’s surface.

Is the new floating bridge built for light rail?

We have built in compatibility for future light rail — should the region determine that light rail should cross the SR 520 corridor.

As constructed, the bridge has six traffic lanes, composed of two general purpose lanes and one HOV/transit lane in each direction, wide shoulders for disabled vehicles, and a 14-foot-wide bicycle and pedestrian path. For future light rail, the roadway could be widened by adding more pontoons along the bridge’s length, then running light rail down the roadway’s center.

When will the new bridge open to traffic?

The bridge’s three westbound lanes opened to traffic on April 11. The three eastbound lanes are scheduled to open April 25.

When will the new bicycle/pedestrian path open?

The SR 520 corridor’s new shared bicycle and pedestrian path will open on the floating bridge in late April — as an “out and back” path that is entered from the Eastside. The path’s Eastside segment, running from 108th Avenue Northeast to the floating bridge, opened in early 2015.

When SR 520’s West Approach Bridge North is completed in mid-2017, bicyclists, joggers and walkers will be able to travel on the path from Bellevue to Seattle’s Montlake neighborhood. When fully built out, the path will extend from Interstate 5 to Redmond.

Will runoff from the new bridge drain directly into Lake Washington?

No. Unlike the old bridge, the new bridge has a stormwater system that collects runoff from the roadway.

Collection wells in the system’s drain pipes capture solids. Runoff water empties into swimming pool-like ponds built in the middle of some pontoons.

Because the pontoons sit 20 feet deep, any sediments that reach the ponds disperse deeper into the lake. Motor oil, antifreeze and other floating pollutants are regularly skimmed off the ponds by bridge-maintenance crews.

Steve Peer is media and construction communications manager for the Washington State Department of Transportation’s SR 520 Bridge Replacement and HOV Program.

Other Stories:

- How ‘belvederes’ and ‘sentinels’ helped make the bridge look the way it does

- Building the bridge was an intricate undertaking

- WSDOT ‘nerve center’ keeps watch over the bridge

- The floating bridge opening has been a long time coming