Surveys

DJC.COM

July 17, 2003

The economics of sustainability

Eco*Arch

Morgan

|

All clients have needs. They need, as Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius said, “firmness,” “commodity” and “delight.” While firmness may well be in the architect’s or engineer’s control, commodity and delight must be directly responsive to the client’s needs.

Then, of course, there is the budget. At first blush, sustainable design may seem to be at odds with budget constraints. This, however, depends on how one defines “budget.”

If budget is the cost of land, construction and design services (first costs), then many sustainability principles will go unused. If life cycle costs are considered, then anything that reduces the cost of maintaining the building over its useful life should be given due consideration.

|

The American Real Estate Association’s yearly polls have disclosed that building owners consistently say that building operations costs are their primary dissatisfaction. Yet, it is rare to see a complete pro-forma for a project that investigates how life-cycle costs can be reduced.

A simple example

Assume a 10,000-square-foot office building (we’ll call it Building “A” for “average”) with a building budget of $100/square foot. The standard design with conventional materials and equipment might produce a $1 million building which costs about $5/square foot/year (or $50,000/year) for energy, repair and maintenance.

Building “S” (sustainable) takes advantage of solar gain while reflecting unwanted heat, uses high R components and systems in the building’s envelope, and brings daylight into the building. Because of the envelope and the reduced lighting load, the building requires less cooling.

Building S’s first costs may be 10 percent higher than Building A’s, making it $100,000 more to build, but it also uses a third less energy and maintenance costs are reduced a like amount due to careful material choices. This will save about $16,000 a year in operating costs.

At this rate, it would take eight years to pay off the initial investment ($100,000) at 8 percent interest. This assumes that there will be no increase in energy rates or maintenance costs (highly unlikely). In fact, if you assume that energy rates will increase at 3 percent a year, the payoff occurs in seven years. At this time, the $100,000 investment in sustainable practice is paid off and is returning $20,000 per year tax free (assuming the savings are kept in the business). These figures are somewhat loose guesses but are close to national averages.

Building S has additional advantages over Building A. Its lower operating costs mean it can charge less per square foot (up to $1/square foot) leasing costs, thus achieving high occupancy earlier than Building A. But this pales before the figures for workers’ salaries.

More savings

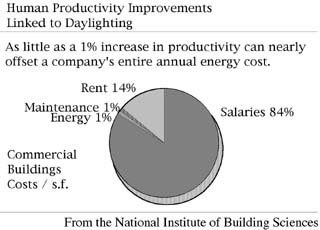

The results of a study released last year by Douglas Mahone of the Heschong Mahone Group for the California Energy Commission titled “Integrated Energy Systems Productivity and Building Science” are illustrated in the graphic. It is a study of productivity in classrooms linked to daylighting, similar to a number of studies on other building types.

Assuming $130 a year per square foot for salaries — and given the fact that sustainable design improves attendance, reduces time loss due to illness and adds productivity — any enhancement of the work place has significant financial incentives. Figures developed by agencies such as GSA, have shown productivity increases of 6-15 percent when comfortable spaces with ample daylight are used.

A 6 percent improvement in productivity would be the same as reducing the salary/square foot figure to $122, a savings of $80,000 a year. If this conservative estimate is added to the energy savings, the $100,000 extra cost of Building S would be returned in a little over one year while saving on productivity and energy costs through the life of the building.

While the building owner and the building user are often not the same, both should gain through the sustainable design approach. The user through higher productivity and reduced utility costs, the owner through lower maintenance costs and better margins due to higher rent rates because of a higher productivity environment.

There are additional benefits of daylit environments, including up to 20 percent higher sales and the prestige of operating out of a sustainable-designed building. Both are hard to quantify, especially prestige.

It can be hoped that the architectural profession will lead in educating our clients to the benefits of the sustainable design approach which will, in turn, enhance our environment (physical and financial) for a positive future.

At the 2000 AIA Convention in Philadelphia, members overwhelmingly backed a resolution that “acknowledge(d) sustainable design as the basis of quality design and responsible practice for AIA architects and, therefore, to integrate sustainable design into AIA practices and procedures.”

With the impetus of the Seattle City Council mandating LEED (US Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design program) requirements in most of the city’s new building and remodeling projects, the need of society to balance our use of environmental resources with the health of the planet, and the cost benefits of a productive environment, it is not surprising that the future of the built environment looks very green.

Chris Morgan, AIA, is an architect and owner of Eco*Arch, a sustainable design architectural firm in Bellingham.

Other Stories:

- Battle over keeping dams rages on

- What’s your vision for Seattle’s future?

- Hat Island gets a drink from the sea

- Foss Waterway cleanup kicks into high gear

- Reclaimed water — a ‘new’ water supply

- LOTT dives into reclaimed water

- Clean air: saving our competitive advantage

- Europe points the way to sustainability

- Old maps handy for site investigations

- Planning for an environmental emergency

- Engineered logjams: salvation for salmon

- Pierce County maps where its rivers move

- Be prepared with a spill management plan

- Development can be beneficial to wetlands

- Check out properties with microbial surveys

- Charting a sustainable course for the Sound

- Water rights no longer a hidden asset

- Laying the path for responsible education

- Squeezing more out of renewable energy

- Controlling mosquitos and the environment

- Beavers back in force in the Seattle area

- Our future: no time or resources to waste

- Port Townsend dock promotes fish habitat

- Brownfields program is here to stay

- Master Builders teaches green homebuilding

- Sculpting a park out of a brownfield

- A salmon-friendly solution on the Snake

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.