Surveys

DJC.COM

June 26, 2008

Financing evolves to benefit the environment

SNW

Grodnik

|

In 2004, the Civic Apartments building in Portland’s Burnside neighborhood had fallen into severe disrepair and had become a problematic property for its owner, the Housing Authority of Portland (HAP). By 2005, however, the building had been transformed.

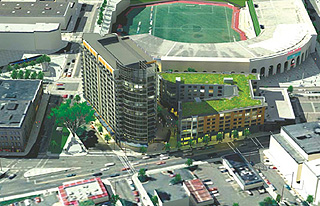

In a prime example of the use of public-private partnerships to reach an environmentally sound and profitable goal, Gerding Edlen Development partnered with HAP to convert the property into a condo tower, low-rise affordable housing and retail mixed-use project that reinvigorated a desolate swath of downtown. The project integrated enhanced public spaces, energy-efficient building techniques and a variety of stormwater management technologies, including courtyard bioswales, a 20,000-square-foot ecoroof and a second-floor terrace.

The affordable housing component of the project is LEED gold-certified, making it one of the most environmentally sustainable low-income housing buildings in the United States. Many of the market-rate units sold quickly — with no advertising beyond a sign posted at the construction site — due to the appeal of a green building, an urban location across the street from a light-rail station and thoughtful design.

Photo courtesy of Housing Association of Portland The once dilapidated Civic Apartments were converted into a mixed-use project that helped reinvigorate Portland’s Burnside neighborhood. The improvements, which included a green roof, were funded by a private-public partnership. |

The underwriter and placement agent on the Civic Apartments deal, SNW (Seattle-Northwest Securities), structured the financing to take advantage of multiple funding sources to pay for the $21.6 million affordable housing component of the project. Those sources included tax-exempt debt financing, Low Income Housing Tax Credit equity, subordinate debt from the Portland Development Commission and HAP, a deferred developer fee, and Oregon Business Energy Tax Credits.

In this case, HAP advanced its mission of providing safe and affordable housing to low-income Portland citizens while Gerding Edlen realized its mission of sustainably developing real estate and generating a profit.

The public-private solution

A public-private partnership involves a service or venture that is funded and operated through a partnership of government and one or more private companies. It offers a way for both partners to capitalize on the financing incentives that contribute to the economics of a green development project. This type of partnership creates an opportunity to access a variety of funding sources, including tax credits, grants, tax-exempt debt and rebates to fund capital costs.

Symbiotic relationships between public and private entities are becoming more and more common. Driven by an increasingly environmentally aware public, as well as new regulations and the landslide of data regarding climate change, municipalities and public utilities are focusing their priorities on energy-efficient public buildings, greenhouse-gas reduction strategies, transit-oriented development, renewable energy projects and land-use planning. Private partners, driven by new business opportunities in green development, emerging environmental regulations and the aspirations of responsible corporate citizenry, are becoming involved with the financing of these projects and are reaping more profits.

A public-private partnership turns on its head the assumption that environmental protection is only philanthropic. This type of partnership yields benefits for both parties: The public entity achieves its mission — whether it’s providing low-income housing, a healthy school environment for students or renewable and reliable electric power — and the private entity profits. It’s a satisfying manifestation of doing well by doing good.

Conserving lands

Another example of a successful public-private partnership is the one that brought together King County, the nonprofit Cascade Land Conservancy and Port Blakely Tree Farms, a private developer with land holdings in King County. The three entities collaborated on the Treemont Development Project (now called Aldarra Ridge), a residential housing project in the midst of a 260-acre working forest in Fall City and beyond the current urban growth boundary.

Under the terms of the partnership, Port Blakely Tree Farms sold the land to Cascade Land Conservancy and gained a tax write-off for selling at a below-market price to a nonprofit. King County then purchased a conservation easement on a portion of the land, funded through the issuance of tax-exempt bonds backed by the county’s Conservation Futures Tax and Real Estate Excise Tax.

Originally, the plan called for construction of 194 homes on the site, with about one house per acre. Due to the partnership, however, development was reduced to 30 homes, which resulted in 120 acres of land being conserved as a working forest, contributing to the water quality of Patterson Creek, minimizing local traffic, and enhancing outdoor recreation and wildlife habitat.

Innovative financing

As these examples illustrate, flexible and well-intentioned public and private partners are necessary to make these structures work. Returns on a sustainably designed project may be lower than returns on conventional developments, and it helps to engage partners who recognize some value in “doing the right thing.”

New incentives that encourage these partnerships are sweetening the deals so that they can be competitive with traditional internal rate-of-return-driven projects. For example, Oregon’s Business Energy Tax Credit program provides a way for tax-exempt entities to benefit from building qualified energy-efficient and renewable-energy projects by allowing them to pass through the tax credits they earn to a private entity that has a tax liability. In practice, this means that an Oregon school district that receives tax credits for improving the energy efficiency of its buildings can sell those credits to a company like Umpqua Bank, which has Oregon state income tax liability. The school district receives a lump-sum payment to offset the cost of the upgrade, and Umpqua Bank uses the tax credits to offset its state income tax obligation.

There was a time when the intersection between finance and environmental protection was not so clear. But now, a number of national and global events, both political and natural, have increased awareness of the value of sustainable projects — and the environmental risk of business as usual. Evolving priorities and business opportunities that mandate green developments are demanding innovative financing options, opening new doors and creating new possibilities.

Ann Grodnik is an assistant vice president in public finance at SNW. The company hosted its sixth annual municipal finance conference, entitled “Financing Sustainable Development in a Volatile Market,” in Seattle last April.

Other Stories:

- Corporate social responsibility turns green

- A green approach to gold mining in the Okanogan

- Homeowners rethink their waterfronts

- Will Earthships save the Earth?

- Municipalities discover the benefits of eco-roofs

- What lies ahead for sustainable design?

- Planning our communities for a low-carbon future

- City, tribe team up on clean water project

- Architectural firm sets a zero-energy goal

- New stormwater discharge challenges loom

- Green building’s future lies in innovation, conservation

- Seattle becomes a hotbed for clean technologies

- Speed up sustainable development with a planned-action EIS

- Avoiding fish-related construction delays

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.