|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

News

| |

|

August 25, 2016

How to design a school restroom that works for everyone

Mahlum Architects

Wilcox

|

Haapala

|

Recent laws, federal directives and high-profile news stories are shining a light on the day-to-day challenges transgender citizens face with using public restroom facilities, and raising questions about civil rights protections and fundamental issues of basic human dignity.

This debate has considerable impact on physical environments across the education spectrum. How do the various toilet or shower needs of building users — be they elementary school, high school or university students, faculty or staff, parents or the public — be met with both dignity and fairness?

While the transgender movement (a phrase that actually encompasses the full LGBTQ community) may be illuminating the issue, toilet privacy affects a much broader group. Each person — whether transgender students and staff or the many non-transgender people who have toilet needs they do not wish to make public — deserves to take care of his, her or their most private human needs without questions from others.

This concept — enhancing equity through privacy — is a basic human right that primary, secondary and higher education institutions can uphold through thoughtful design solutions when retrofitting or building new facilities.

Cost fears

When equitable toilet design in the United States was standardized via the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) 1990, accessible toilet designs typically resulted in an individual (single occupant) room. In some cases, families with young children or adult caregivers were accommodated with family-style bathrooms.

In Washington and Oregon, additional statutes protect equal access to all genders, but for school districts with limited budgets, established facilities and deep-rooted social practices, relinquishing the traditional bathroom model is daunting.

Until recently, restroom design had almost become an afterthought for architects. Rows of stalls opposite rows of wash basins were designated only for males or for females. Such designs involved predictable plumbing, mechanical exhaust, and fixture costs.

Alternative design strategies that provide adequate numbers of individual toilet rooms can exponentially increase costs through additional plumbing, ductwork, square footage and ADA compliance, as well as invalidate some USGBC LEED points.

Colleges and universities may more easily implement equitable bathroom designs than K-12 school districts because users are older, more diverse, spread across many buildings, and tend toward critical thinking and open-mindedness. With their 24/7 occupancy, residence halls tend toward more equitable toilets and showers, but fear remains that enhanced design solutions will escalate costs, consume space, and drive up room rates.

Toilets and showers in residence halls have traditionally been grouped by gender per floor or per community, but this limits a campus’s flexibility to fill empty bedrooms. Suite-style bathrooms serving smaller clusters of students potentially mitigate gender-segregated restrooms, but can cost more.

Even as schools, colleges and universities plan for more equitable restroom design, building codes have not yet caught up. Most jurisdictions determine required restrooms by calculating a ratio of women to men for typical occupancy. Some localities have altered the ratios, but the results are similar.

To meet ADA requirements, one larger, more private stall is included per floor or area. To save costs or preserve a sense of cleanliness, this usually doubles as the staff bathroom, a transgender accommodation, or is locked for approved users only. However, such policies connote these restrooms as “separate” or “different” especially among young students just learning to navigate social customs and are keen to fit in with their peers.

Within this multi-layered context, Mahlum has developed solutions with several clients to design toilets, showers and restroom facilities that meet the needs of transgender and non-transgender people alike, affording enhanced function and privacy.

Alternative solutions

Mercer Island School District wanted their kindergarteners to be accommodated throughout the new Northwood Elementary School. To meet this desired flexibility and maximize restroom equity, the design team placed individual toilet rooms across from classrooms in many places on each floor, rather than include singular toilet banks at the end of halls.

Since the district intends to keep them unlocked and available to all students, the solution offers toilet equity while boosting program flexibility, reducing time lost to toilet transitions, decreasing opportunities for bullying, and increasing feelings of inclusion.

For the renovation and expansion of the historic Grant High School in the Portland Public School District, Mahlum’s design solution will go even further.

In 2013, Grant had 10 students who openly identified as transgender, according to school administrators. Since one of the top reasons transgender students drop out is because they feel uncomfortable or unsafe going to the bathroom at school, administrators prioritized toilet equity in their existing facility.

Four student bathrooms and two staff bathrooms — all individual rooms — were designated as gender-inclusive. As a result of their popularity with all students, providing equitable toilet facilities with enhanced privacy for all 1,700 students became an essential directive in Mahlum’s redesign of Grant, which began in 2015.

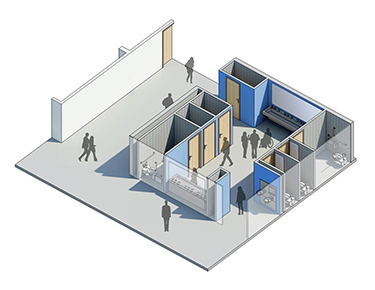

In the team’s solution, all existing “gang-style” bathrooms will disappear — replaced by individual toilet rooms with full doors open to a shared space for wash basins and drinking fountains. Two ways in and out eliminate the feeling of going into a “dead-end” room, increasing safety and security. Use by staff and students will further enhance safety.

Signed with a simple pictorial representation of a toilet, not the ubiquitous “his” (pants), “hers” (skirt), or “their” (both), the toilet room is open for use by all. When the renovation is complete in 2019, Grant High School will become the first in the district — and one of the few in the nation — to house 100 percent inclusive bathrooms.

Shower rooms

Sackett Hall, a 1960s-era residence hall at Oregon State University, has been a workhorse facility for University Housing and Dining Services (UHDS), providing students with smaller-scale communities of 16 students per floor. Only one gang-style restroom and shower facility served each floor, so UHDS could assign each floor to either males or females.

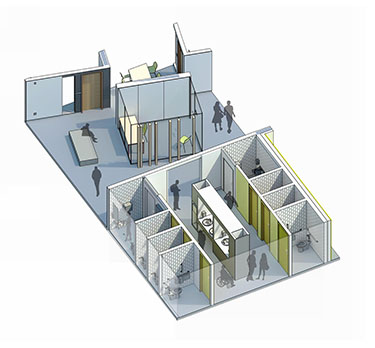

Mahlum worked with UHDS to reconfigure the restrooms to enhance privacy and ADA access. The new spaces incorporate toilet rooms built with real walls, shower rooms complete with benches and changing areas, and lockable door hardware.

“This solution not only allowed us to create more inclusive spaces and broaden access, but we were also able to maintain strong community culture, especially for our first-year communities,” says Patrick Robinson, associate director of Facilities Maintenance & Construction for UHDS at Oregon State University.

“The restrooms have been broadly well received and the design is currently used to inform our approach as we work to modernize and retrofit our legacy facilities.”

For a new residence hall currently under construction at University of Oregon, student listening sessions revealed a strong desire for gender-inclusive living units with private bathrooms, as well as visible equity and inclusion in ground-level public restrooms and common areas. As a result, 100 percent private toilet rooms and community lavatories are provided for all study, maker/hacker and academic spaces, as well as community kitchens.

Monitoring behavior

Individual toilet stalls can provoke lingering behavioral concerns for administrators, who desire ways to passively monitor behavior. However, truly universal restrooms, where staff use the same facilities as students, permit more effective passive monitoring. Boys and girls are not left alone — instead they interact with each other and with adults with less segregation — a dynamic that often occurs at home and is commonplace outside the U.S.

Using the toilet is one of humanity’s most essential needs. It is also one of our most private acts, with the power to affect self-esteem, health and security. Creating inclusive toilets in schools and universities makes sense for everyone for every reason because the long-term value is so much greater than meeting the needs of a few individuals.

As we struggle with understanding what communities need and how to meet federal regulations, we must quickly find a design vocabulary, inclusive iconography and code guidelines that reflect best practices. And most of all, we must place equity and human dignity at the center of these conversations.

JoAnn Hindmarsh Wilcox is an associate principal at Mahlum Architects and a lead designer for its K-12 studio. Kurt Haapala is a partner at Mahlum and an industry leader in the planning and design of student life and housing facilities.

Other Stories:

- When does renovating a school mean bringing it ‘up to code’?

- New Mount Si High will sit atop 4,800 stone columns

- School projects in remote Alaskan villages face tall hurdles

- Lynden Elementary: from concept to completion in 22 months flat

- Learning center in Tacoma Park will serve students and the community

- Clark College creating a regional hub for STEM

- ‘Dark,’ ‘maze-like’ student union gets a big makeover

- Tahoma School District responds quickly to surging enrollment