How is the brownfield expirament working?

By THOMAS BOYDELL

Seneca Consulting Group

Preserving and recycling industrial land involves issues too intricate, and environmental consequences too important, to be governed by an attitude of opposition and mistrust between environmental and economic interests. A more collaborative approach is required, which is at the heart of brownfields initiatives.

The national brownfields experiment is an effort funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The program consists of grants to state and local governments. These grants provide seed capital for creative approaches to environmental cleanup and redevelopment of older industrial sites throughout the country.

The experiment is expected to achieve more effective cleanup and reuse strategies through local experimentation and the evolution of state expertise and policy change that will be carefully coordinated. This new approach uses policy tools to connect environmental protection and business growth. Some of the results across the country seen so far include: innovative approaches to assessment, new technologies, new state financing programs, better cost and risk management, and larger-scale cleanups.

|

Some brownfield sites such as Seattle's famous Hat 'n Boots gas station are still waiting for redevelopment.

|

This experiment has the power to reverse a history of neglecting community and environmental needs. Ironically, the greatest obstacle to its success, may be the distrust the pattern of neglect has itself engendered.

From 1993 to 1997, U.S. EPA funded 121 pilots. Another 107 have been announced this year, including grants of $200,000 each for Ballard/Interbay and the City of Everett's Lowell Park area. In the past, pilots have been awarded in the state of Washington to the Duwamish Coalition in Seattle-King County, the Puyallup Indian Tribe, the City of Tacoma and the Port of Bellingham. In the Pacific Northwest, other pilots are underway in Oregon, Idaho and Alaska.

In 1998, the Duwamish Coalition and Portland initiatives also received a Showcase Cities award from the Office of Vice President Gore. This designation makes available additional federal funding and technical assistance to a few outstanding brownfields programs.

What is the Duwamish Coalition?

The Duwamish Coalition's projects grew out of a combination of a strategic response to growth management needs, the success of Port projects, calls to action by various community, business and labor groups, and economic research conducted by Seattle and King County governments. The Coalition was established by a Resolution of the King County Council in early 1994.

The Duwamish Coalition quickly grew to more than 250 active members meeting monthly. The steering committee, five subcommittees and technical groups tackled a large range of problems, from water quality and habitat restoration issues to the economics of environmental remediation and redevelopment.

Staff teams of technical experts from business and government supported each of the subcommittees and technical groups, and a team of lead staff met biweekly to coordinate work among all of the different groups. Monthly meetings were held through 1996, and then projects passed to government staff to implement.

Local projects

The Duwamish Coalition effort is one of the best of the big city brownfields programs. But, it is different. It emphasizes market-based solutions that make industrial redevelopment more profitable, rather than depending on direct government intervention and subsidies.

Solving the brownfields problem means limiting perceived risk and providing incentives.

The Southwest Harbor Project demonstrated how the Port of Seattle could lower costs by dealing with environmental cleanup and development options simultaneously. The next task for the coalition was to make this process available to average developers and business owners in the Duwamish area with 2- to 10-acre properties and more limited financing.

The core strategy undertaken includes:

Petroleum guidance: Petroleum is the most common environmental concern, present at 85 percent of Duwamish sites. The Duwamish Coalition has undertaken a major research project to better inform state policies on petroleum. The goal is to put in place a risk-based framework for evaluating toxicity based on fractionation of the carbon range and better analysis of site-specific conditions.

Federal and local funding for this project has amounted to about $700,000 plus almost as much in staffing assistance. The private sector has participated through technical assistance and by providing case-study sites. This three-year project is nearly complete, its recommendations folded into the proposed MTCA amendments currently undergoing revision and public review.

The project builds off similar risk-based studies and guidance developed by a national workgroup and by government agencies in Texas, Massachusetts and British Columbia. However, the Duwamish Coalition is the only brownfields pilot in the nation undertaking such a major research project. Other cities and states are equally concerned about petroleum. They are closely watching our effort and the innovations produced, such as in laboratory analytic methods.

Groundwater mapping and policy-setting: This part of the strategy assembles basic data needed to reduce site assessment costs and better pinpoint risks to the water supply. It includes aggregating subsurface and hydrogeology data to create a conceptual model of groundwater movements, documentation of brackish zones and tidal influence on groundwater, numeric flow modeling, identification of state-classified contaminated sites, and a 75-year history of land uses. The data, modeling and maps cover a 9,000-acre area that stretches from the Kingdome down through Tukwila.

This $225,000 project is largely complete, with reports and data under review by the Department of Ecology. The Geographic Information System (GIS) database is available either in the Environmental Extension Service or for purchase from the City of Seattle's GIS division.

Emeryville, Calif., has also mapped groundwater. Although its project covers less than 1,000 acres, it goes further by publicly underwriting liability for any pollution to the aquifer or bay. The costs of this liability are charged back to businesses in the form of a special tax assessment.

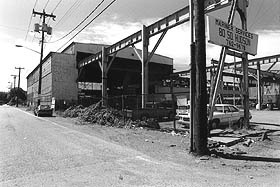

|

The former Wheelabrator site on South Hudson Street as it looked before Alaskan Copper & Brass bought the property, cleaned it up and set up a sheet steel cutting plant in the refurbished buildings.

|

Cleveland is the only other city to actively focus on groundwater liability issues. However, several other cities have used GIS to enhance the tracking of environmental information.

Once tracked in this fashion, a better integration with land use permits is possible. This has been accomplished by Emeryville, as well as Buffalo, Rochester and Knoxville, Tenn. Similarly, Oregon is piloting a state permit information system that combines institutional control information with utility information. This "know before you dig" type of program better ensures public protection, whenever environmental measures involve containment instead of removal actions.

Environmental extension service: A technical assistance center, primarily for the benefit of smaller industrial businesses has been established to help with waste management and pollution cleanup issues. The center includes a library, GIS workstation that is linked to city, county and state systems, and an Internet site with linkages to regional resources and environmental firms. Local government and foundations have provided funding. Local environmental firms donate technical assistance to business owners.

The EES has just completed its 15-month startup period. So far 89 businesses have been helped by the EES, with an average cost savings of more than $2,000 per business. The EES is now at the forefront of the integration of Duwamish efforts. Other cities and states provide technical assistance. However, the Duwamish EES is the first independent center of its kind. EES activities are intended to expand to other parts of Seattle and King County later this year.

The Duwamish strategy consists mainly of regulatory reform, financing and technical assistance. This was designed to leverage funding to more quickly affect a large number of properties. It has also produced innovations in analytic methods, risk and liability determination as well as a better integration of pollution prevention and cleanup programs.

As some projects approach completion and the EES gets set to expand its services, other cities and states are watching and learning from us. We are also watching and learning from them. In this way, the Duwamish effort has been an integral player in the national effort.

However, efforts here are different from those in cities like Chicago, Cleveland and Pittsburgh. There, the focus is mainly on taking ownership of brownfields, conducting cleanup and then remarketing the property. Many of these cities are starting with tax-abandoned properties, which Seattle, Tukwila and King County have been spared. Some cities like New Orleans, Indianapolis, Rochester and Boston are focusing on a variety of smaller properties or business expansions first. Others, such as Des Moines, Iowa; Sioux Falls, S.D.; and Knoxville, are assembling land and redesigning large sections of downtown.

Going further

The Duwamish effort could be taken further. A range of new financial mechanisms and lender liability reforms were proposed by the Duwamish Coalition. Few have been put in place. Several industrial sites were also selected for demonstrating various public-private actions that could resolve redevelopment problems, but little has been accomplished so far.

Community Development Block Grants and Section 108 loan guarantees have been successfully leveraged in cities like Chicago and Philadelphia and in several areas of Massachusetts. Currently, a similar financing strategy is under consideration for one brownfield site in South Park and another in Rainier Valley. If successful, these projects could be a model for other local brownfields projects.

There are excellent models available for state financing and site assessment programs. States we could look to include Florida, New Jersey, New York, Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Illinois. Tax increment financing or special tax assessments have also been used in California and in cities like Sioux Falls, Des Moines and St. Paul, Minn.

Public-private collaboration

The Duwamish Coalition has succeeded, in large part, by applying private-sector organizing principles such as communication and team building. Communication was strengthened by funding research to analyze market conditions and identify problems, by sponsoring public outreach and joint-training workshops, and by an emphasis on information sharing among the members.

These initiatives created a common basis for dialogue among Coalition members with very different technical backgrounds and agendas. Team building was encouraged by the use of learning models, a bottoms-up approach to leadership, a willingness to listen and share creative ideas, and empowerment of staff teams that would be responsible for implementing projects.

A look at other cities

In most cities with brownfields programs, a similar story proves the value of partnership and community participation in decision making. In Santa Barbara County, for instance, a community group has produced leadership in a poor, unincorporated area of the Goleta Valley, becoming a de facto town government where none existed. The group's accomplishments have included a five-year limitation on the county's use of eminent domain in favor of negotiated strategies.

|

The Alaska Copper & Brass offices are a brownfields success story.

|

Similarly, an environmental coalition in San Diego and citizens commission in St. Paul select properties and prioritize reuse strategies that local government implements.

In Chicago, Cleveland and Emeryville, Calif., representatives of business and lenders met with the community in forums similar to the Duwamish Coalition, creating large new financing programs. Buffalo's effort began with a comprehensive "vision plan" by business and community leaders that now guides redevelopment efforts in that city.

Small towns in central Massachusetts and Connecticut's Brass Valley have formed regional authorities where decisions are made in town meetings. And, the Cape Charles, Va., community led in the creation of a program that has revived an area long considered hopeless.

What is the future?

The prognosis for the success of the Duwamish projects is extremely good. Many are just now reaching completion and the Environmental Extension Service has only now completed its initial 15-month startup period. The full impact is yet to be seen. The principal limitation is that it takes time to build trust and complete projects.

Cynicism, political agendas and the need to create "wins" for different constituent groups can make it difficult to keep a coalition together over an extended period. In the meantime, key staff can be pulled off to other assignments or other priorities divert attention.

One risk is that government partners in the Duwamish projects may have under-invested, despite more than $2 million in funding and staff time so far. A second is that policy changes by regulatory agencies must be followed by cultural changes in all government agencies that are connected with the environmental cleanup and redevelopment processes. Otherwise, new rules run up against unintentional roadblocks that can frustrate regulators and developers alike.

Another risk is that the benefits of brownfields projects may not be widely shared, but used primarily to support port or rail yard expansion, or other large projects. Wider dissemination of information to the public and small businesses, as is done by the Environmental Extension Service, can reduce that risk.

The nature of these technically-oriented projects is that many problems are connected to other problems, leading to challenges that keep growing. For example, petroleum contamination issues involve new ASTM standards, which are linked to national questions about contaminant treatment methods and transport modeling, and linking back to numeric pathway modeling concerns for groundwater evaluations.

Momentum is hard to maintain, especially when there is not enough understanding that some types of decisions have real budget and schedule implications that can derail a project.

Although its tasks are not yet finished, the Duwamish Coalition has accomplished a lot with few resources. A commitment to innovation and balancing political interests has made a difference.

In many ways, the most important role of local government was to "create the table" and build a shared body of knowledge as an essential foundation for successful dialogue.

Thomas Boydell of the Seneca Consulting Group was a principal architect of Seattle's brownfields strategy. He is an advisor on finance, economic development and brownfields issues for the City of Seattle, Duwamish Coalition, and various other cities and industrial businesses. He is working with the U.S. EPA in charting the progress of the national brownfields pilot effort and creating networking opportunities among pilot cities.

Copyright © 1998 Seattle Daily Journal of Commerce.

| ![[Environmental Outlook]](logo.jpg)

![[Environmental Outlook]](logo.jpg)