DJC.COM

May 20, 2004

Library lights lift a heavy load

Candela

Claire Frazier

|

The King County and Seattle library systems have delivered a collection of architectural gems over the past 15 years, created by many of the best architecture firms in the area. Despite limited budgets, or perhaps because of them, architects have made wise and creative use of public funds to produce outstanding structures.

Balancing tight budgets against the desire to provide neighborhoods with community centers they can be proud of, design teams have sought ways to create visually interesting, functional and durable spaces that look more costly than they are.

As a result, today's libraries are often large open spaces with exposed structure and few walls. They have become active, noisy, vital places.

Locating multiple functions within those spaces can present a challenge for the lighting designer. Balance must be found within the framework of competing visual requirements.

It can be difficult to enhance the architecture while meeting tightening energy codes, controlling glare and providing maintainable systems and adequate light levels.

Balancing act

Photos by Art Grice

Lighting fixtures and mechanical equipment at Auburn Library are coordinated to form a clean, uncluttered system. Artwork is softly lit for visual rest, while the copy room is lit brightly for visibility.

|

Using the architecture to help distribute light around the space can both increase visual comfort and reveal interesting architectural features. Indirect lighting accomplishes these imperatives, but often doesn't provide adequate light levels to accommodate the reading requirements of older library patrons.

Supplementing the indirect light with more directed downlight can increase light levels, but also increases the potential for glare on computer screens. Glare-control requires good quality shielding on light fixtures and careful placement of the fixtures themselves.

Combining all these functions into a single type of light fixture can help prevent visual chaos, as can coordination of lighting locations, mechanical equipment and building structural elements.

Auburn Library offers an excellent example of this technique.

Light fixtures and mechanical ducts, located in tandem, pass through carefully designed trusses. Uplight from the light fixtures provides an even wash of light across the ceiling that balances the brighter apertures, alleviating glare.

Sophisticated reflectors inside the light fixtures provide wide distribution of the light, allowing maximum spacing between the rows. The result is a clean architectural space that feels expansive and relaxed.

Visual rest

The custom stack light at Issaquah Library offers task lighting for reading as well as ambient lighting.

|

Libraries remain intensely visual and contemplative places where we read and think. For reading, we need adequate light. For thinking, we need quiet corners with something interesting to view — a focus for daydreaming.

In fact, even for reading we need a place to periodically rest our eyes. Visual rest is one reason artworks have been incorporated into library projects.

At Auburn Library, the artwork is a series of glass panels by Dennis Evans and Nancy Mee, located high on the wall and visible throughout the room. Soft flood lighting provides sufficient light to see details without creating excessive contrast that would distract from the more detailed visual activity below.

In the children's area at Delridge Library, the light fixtures themselves provide visual rest. A playful swirl of ribbon track holds colorful pendants that signal a special area and provide a visual focus for adults settled quietly across the room. Accent lights provide light for colorful displays on the walls, while whimsical short stools tell children “this is your corner.”

This kind of identifying image is very helpful in providing clues to users about where different functions are located in a library. The architecture and lighting can work together to make it easy for visitors to find meeting rooms, circulation desks, restrooms and information boards.

Rather than rely on overworked librarians at the circulation desk to orient people toward those spaces, the lighting can cue them visually.

The copy room at Auburn Library opens off the main space. In contrast to the subdued color around the doorway, the light walls and cabinets in the copy room, illuminated with a wash of light down the wall, draw attention to the information racks. As one approaches the circulation desk, the copy room becomes obvious.

Keeping furniture in place

When lighting a large space, fixtures high in the space can be positive architecturally and visually, but maintaining them can be challenging.

Reaching light fixtures to change lamps without having to rearrange furniture is a priority for libraries — one that needs to be seriously considered during the design process.

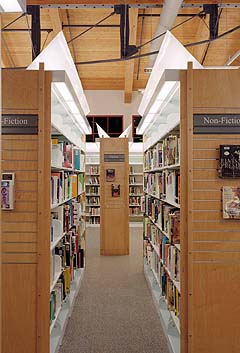

This issue is particularly important where full-height book stacks are lined up in tight configurations. Book stacks tend to soak up light due to narrow aisles and dark book covers.

A “stack light” fixture, located above the top shelf, can provide a wash of light down the vertical surface of the shelves, making it easy to read the titles, even on the bottom shelves.

Many stack light fixtures tend to be overly bright to look at and uncomfortable to be under.

At Issaquah Library, this problem was solved by designing a custom fixture that not only lights the books, it also reflects light across the aisle and up to the ceiling. No pendant fixtures are located over these stacks, so there are no maintenance problems, and yet the entire area feels just as luminous as other areas.

The Seattle energy code now requires automatic lighting controls that respond to daylight levels in the space. Because switching lights off suddenly can be disturbing to occupants who are trying to concentrate, many new buildings are incorporating automatic dimming controls.

This energy-saving technique will allow Seattle public libraries to harvest substantial energy savings without users noticing the electric lights are changing. Look for this farsighted feature in Northeast, Ballard and Southwest branch libraries.

As the functions, collections and users change with the evolution of technology, our neighborhood libraries will continue to evolve as well. The need to maintain a visually comfortable, functional and interesting environment, however, will always remain.

Mary Claire Frazier is principal at Candela Architectural Lighting Consultants, based in Seattle.

Other Stories:

- Do we really need libraries anymore?

- Living rooms for urban neighborhoods

- Dozens of library projects on tap for Seattle, King County

- Libraries: the next must-have amenity

- Library's tech system is also daring and elegant

- Intuitive design yields unlikely results

- Divining the cost of an oddball building

- Nuts and bolts shape the library's unique design

- Neighborhood libraries get big-city treatment

- College libraries cater to widening needs

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.