Surveys

Awards

DJC.COM

March 27, 2008

Keep buildings in shape with facility condition indexing

Mark G. Anderson Consultants

Howie

|

In the U.S. we are conditioned to assume that real estate appreciates. We figure that if we can get it built, our troubles are over, and appreciation will carry us into a valuable real estate future. Facility professionals tell us otherwise. Physical depreciation is real, and as any auto owner knows, everything wears out, usually quicker than we think.

While getting a building built these days is a major undertaking — with ever-burgeoning system complexities and specialists — it’s no small feat to take care of these buildings after occupancy. After specialist design, construction and commissioning team members are off to the next job, a facilities specialist is left with a stack of manuals, a year’s worth of warranty call backs and a growing work-order list from occupants. As a building grows older, age-related repairs emerge, and annual facility budgeting is often overwhelmed. Getting a handle on all this while still tackling the day-to-day work orders is tough.

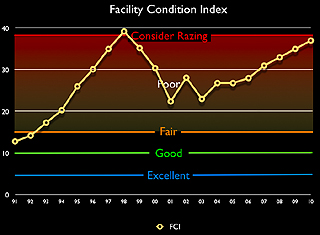

Recently, forward-thinking facility professionals have found solace in a rational planning tool called facility condition indexing (FCI). This measurement tool quantifies a building’s condition as a ratio of its deferred maintenance divided by its replacement value. A .10 FCI building is in excellent repair and a .35 FCI building is very poor.

FCI norms include higher education’s surprisingly high .30 average. For institutional and nonprofit owner occupants particularly, getting attention at budget time is an annual struggle, generally resulting in a growing backlog of deferred but ultimately unavoidable repairs and capital renewals. Even such renowned institutions as the Smithsonian are running their buildings with surprisingly antiquated infrastructures.

The complementary benchmark to FCI is the annual amount which should be put aside to effectively maintain and renew a building. Historically, if 4 percent of a facility’s replacement value is put aside each year, it will cover maintenance and capital renewal costs for 50 years, and then provide enough for full building replacement or rehabilitation. This 4 percent is broken down into 1.5 percent for yearly maintenance and 2.5 percent for periodic capital renewals.

A parallel can be drawn to the cost of maintaining a car. It’s reasonable to assume that over a 10-year lifespan of a $20,000 car, one would spend an average of 4 percent or $800 annually in maintenance, repairs and replacements. Who can argue with this?

The FCI process

The key to effective use of the FCI tool is to keep the facility condition information structure simple, understandable by all, and easily updateable. The process for creating this ongoing management tool is as follows:

1. Establish each facility’s replacement value (appraisals or less formal self-assessments will do).

2. Perform a high-level facility condition assessment (self-performed or with design professionals).

3. Identify needed improvement projects over a five- to 10-year time horizon, categorized as life-cycle renewals, component corrections or capital improvements.

4. Establish budgetary pricing for each project (use a good professional cost estimator or general contractor, following a Uniformat structure).

5. Develop a simple updateable database to support a multi-year budgeting process (use an alpha-numeric spreadsheet/database, or consider a Web-based approach as defined in http://www.facilityportfolios.com).

FCI benefits

There are several noteworthy benefits to this approach to predicting life-cycle repairs and replacements:

• Financial people quickly grasp the logic and get on board with a multi-year budgeting process coupled with a replacement value rationale for expenditure.

• When considering new facilities, an organization’s database of current replacement values and FCIs provides a springboard for budgeting. It also keeps the ongoing cost of all capital renewals for the entire existing building stock at the forefront. Capital project and operations-and-maintenance specialists find common ground in this, and adversarial traditions often fall away.

• With the realization that everything ultimately wears out, life-cycle decision making becomes routine. As higher-efficiency, more environmentally appropriate equipment and materials emerge, it is now easier to make the economic case for them. This ongoing incremental renewal strategy is the most practical way to implement LEED principles on existing buildings, which amount to 95 percent of the U.S. building stock.

• Similarly, there is an acknowledgement that all buildings face mid-life crises when major systems wear out, necessitating replacements coupled with significant occupancy disruptions. These nip and tucks can often be done on multiple systems, and are least disruptive when a partnership is struck between the building operators and capital project specialists.

A long-time proponent of the FCI system is Kevin Folsom, director of facilities at Dallas Theological Seminary. His “pay me now or pay me later” slogan has yielded a campus of well-oiled machines.

“Our facility condition index report is fully integrated into our master planning process,” Folsom said. “Renewal and reuse of existing facilities is always considered before a new facility is added to the inventory. This affords us the ability to maximize use of an old facility to meet current needs, and to simultaneously eliminate deferred maintenance. Additionally, this provides a means to incorporate the latest environmental sustainable technologies for a high-performing facility.”

Lewis Howie is vice president at Mark G. Anderson Consultants, acting as an owner’s representative and leading large, complex capital programs through strategic planning, design, construction, commissioning and move-in. He works with owner-occupants, developers, property managers, architects, engineers and general contractors on diverse projects.

Other Stories:

- Construction training is good for your bottom line

- How to take over a construction project

- Top 10 tax tips for contractors and developers

- Is your insurance giving you a bad wrap?

- It pays to have a stormwater permit strategy

- UW builds its construction management program

- Watch out for changing immigration laws

- Are your windows really Energy Stars?

- The shocking state of our national infrastructure

- Partner up for successful projects

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.