Surveys

DJC.COM

April 28, 2005

Putting the art back into garden design

Brooks Kolb LLC Landscape Architecture

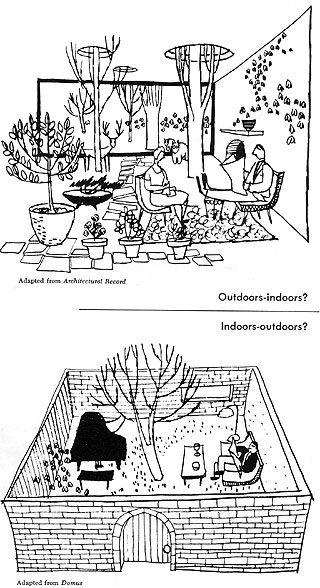

Sketches by Garrett Eckbo from “The Art of Home Landscaping”

These Eckbo sketches illustrate how outdoor spaces can be designed either to bring the outdoors in, or to take the indoors out, furnishing a small garden the way one would furnish a living room. Although the room is furnished, note that its most important feature is that it is fundamentally open and uncrowded. The void in the center contrasts with the solid edges, leading one to perceive it as a contained space. |

At a time when landscape architects are focusing on ecological sustainability and green building, it is valuable to remember that there is an art to landscape architecture as well.

Landscape architects view design as creating or transforming space, rather than combining plant textures and colors. It is this talent that sets landscape architects apart from horticulturists, gardeners and landscape contractors. Some avant-garde landscape architects have even underscored this point by designing outdoor rooms without using any plants at all.

Today, the profession is embracing planting design once again, with the proviso that the plants are at the service of the spatial concept, rather than the other way around.

All gardens are essentially spaces defined by four edges. The edges can either be man-made walls or living screens of plants. The floor is the earth, whether paved or unpaved, and as landscape architect Garrett Eckbo put it, "The sky is the ceiling."

Historic influences

The basic outdoor room is an exercise in one-point perspective — no matter how small or large, it is often set up to be viewed from a single vantage point such as a wide doorway.

Walled Islamic gardens, including the intimate Moorish gardens of Granada and even the vast expanses of the Taj Mahal, were organized around a perspective view but also around the related principle of two perpendicular axes intersecting in the exact center of the space. This method of dividing a simple square or rectangle into equal quadrants also applied to medieval gardens and to portions of the most memorable Italian Renaissance gardens.

A space divided into quadrants is one which presents essentially the same view from the center of all four sides: it is bilaterally symmetrical. The most iconic example is the typical medieval cloister garden, a square surrounded by colonnaded walkways (the cloisters) and punctuated with a baptismal font at the exact center.

While ostensibly religious in origin — depicting the four rivers in the garden of Eden, the cross carried by Jesus or the four quadrants of paradise described in the Koran — this configuration also relates to a mathematical description of space.

Mathematical space is defined by the intersection of the two horizontal x and y axes with the vertical (z axis) at their centerpoint and this configuration is translated poetically into landscape design by the central fountain and axial boxwood hedges of cloisters and other formal gardens.

In the Renaissance, as the science of perspective was rediscovered and embraced, this arrangement came to honor the symmetry of man, as so famously illustrated in Leonardo Da Vinci's sketch of "Vitruvian Man."

Paradigm shifts

As garden design evolved in the 17th century, two major paradigm shifts occurred. The first was a great jump in scale from the intimate spaces of medieval and Moorish courtyard gardens to the vast pomp of French formal gardens, as mastered by Andre Le Notre. Here, two axes still intersect, but they have become giant canals measured in miles rather than paths measured in feet. There is still a primary view out toward a distant statue, seen from a chateau, but the vistas from the other three arms of the cross are entirely different: on the main axis there is a view back toward the symmetrical chateau and on the side canals there are less formal, more bucolic views.

The second paradigm shift came with the English landscape garden movement of the 18th century. Its impact cannot be exaggerated because by "jumping the wall … to see that all of nature is a garden," the axial relationships of flat floors and vertical walls were thrown out the window. The entire view from the house was at the landscape architect's disposal — a great valley bounded by the ridgelines of undulating hillsides, an entire watershed.

Walls and axes have returned in modern times, but only based on the constraints of small urban sites rather than the imperatives of defending a walled space from invaders or protecting an oasis from surrounding desert heat and winds.

At first glance it seems that the English landscape garden, conceived for the nobility and reinterpreted for public consumption by Frederick Law Olmsted in New York's Central Park, turns its back on the basic principles of space-making: a floor, four walls and an open ceiling. Yet even in Central Park's infancy, when the city had not extended uptown to meet the park, this great landscape was visually bounded by the subtle ridgelines at its corners.

Modern garden design

Modern landscape architects have built on this history of space-making, sometimes invoking one or more paradigms to fit the uniqueness of each project.

Brazilian Roberto Burle Marx, a master of artistic composition, created "English" parks from the lush colors and textures of the tropical vegetation near Rio de Janeiro.

Tommy Church created distinctive gardens that express the personalities and lifestyles of his San Francisco Bay Area clients.

Fast on Church's heels, as suburban sprawl began to take over postwar California, Eckbo created informal backyard gardens, allowing a growing middle class to share in the delights of indoor/outdoor living.

At the Miller Garden in Columbus, Ind., Dan Kiley re-introduced formal axes but shed the relentless symmetry of LeNotre's legacy.

No matter which approach is taken, the overall spatial composition — more than its furnishings — guarantees that a design has a place in the art of landscape architecture.

Brooks Kolb, ASLA, is principal of Brooks Kolb LLC Landscape Architecture in Seattle. He specializes in residential garden design.

Other Stories:

- Golf courses go high-tech to stay green

- WSU study says plants are good for us

- Group gets kids thinking about landscape design

- Lake Union park becomes environmental showcase

- 9 ways landscaping can look AND be green

- Homeless youths get a taste of gardening

- Show off your stormwater runoff

- Green spaces are good medicine

- Landscape architecture students take on tsunami

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.