Surveys

DJC.COM

April 10, 2003

Olympic Sculpture Park: a Northwest collage

Charles Anderson Landscape Architecture

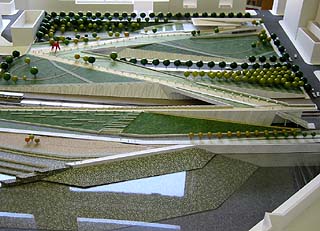

Prototypical landscapes in the Olympic Sculpture Park, from right to left: “Garden of the Ancient,” “Garden of the City” and “Garden of the Sound.” |

Seattle Art Museum’s Olympic Sculpture Park will be a 9-acre collage of landscape, art and architecture, an urban sculpture park unlike any other.

Shifting sands, rising tides, giant horsetails, yellow quaking leaves, fern beds, pine cones and snow covered mountains will all be framed for view along with works of art like Alexander Calder’s “Eagle.” Orange cranes, container ships and ferries will have their places in the landscape along with new exhibition space, gravel paths and underground parking.

It is a work of ongoing collaboration between the museum, artists, the design team and many others.

Marion Weiss and Michael Manfredi of Weiss/Manfredi Architects, leading the design team, recognized the complexity of the context of the site and quickly embraced them.

“Our design is conceived as a continuous surface that unfolds as a landscape for art, wandering from the city across highway and rail lines to reach the water’s edge,” said Weiss. “This new topography, sculpted to rise over the existing infrastructure, creates an uninterrupted landform for sculpture, offering settings to view the city and the sound. This design creates connections where separation has existed, illuminating the immeasurable power of an invented setting that brings art, city and sound together — implicitly questioning where the art begins and where the art ends.”

The overall form for the park resembles a “Z” and features a central path with two bridges, one over Elliott Avenue and the other over the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad tracks. It will connect the urban core of the city to the vast landscape of Puget Sound and Myrtle Edwards Park. The design celebrates a site remarkable for its dual connections to the city and the surrounding region. These connections are also reflected in a series of gardens creating several distinctive prototypical landscapes found in the Pacific Northwest.

The pavilion, the only building in the park, sits at the intersection of Western Avenue and Broad Street. Housing exhibitions and events, it will signal the institutional function of the park and connect with the urban context. While it is a part of the city, the building’s glass and metal surfaces will reflect and respond to the ever changing sky and landscape.

Adjacent to the pavilion, the “Garden of the Ancient” establishes the beginning of the park and also the beginning of a mountain-to-sea narrative of the Northwest natural environment. The garden is inspired by our Northwest forests, the most densely forested region in North America. Featuring our native spruce, cedar and hemlock, trees of extraordinary height and lifespan, it will recall the essence of our evergreen forests.

The challenge will be to evoke the timelessness of our temperate rainforest. This is done in a number of ways, from transplanting large conifers, carefully assembling native plant communities, reusing water and varying the topography, to importing salvaged old growth soils, boulders and woody debris. In addition to native plant species, a group of “living fossils” (or trees that once lived here over 200 million years ago and were fed upon by dinosaurs) will also be highlighted. Ginkgo, dawn redwood, sago palm, maidenhair fern, and giant horsetail are a few of the curiosities that will connect the garden with trees that were once a part of this landscape.

The park form resembles a “Z.” A central path with two bridges connects city to sound. |

While the evergreen is the dominant tree in our region, it is the deciduous tree that colonizes a newly disturbed site. Reaching maturity in 20 to 30 years, they can dominate a site for decades. These are the primary trees of the “Garden of the City.” A triangle shaped grid of trees, including quaking aspen and paper birch, will dramatically express the seasons of a civilized wild.

Located on the shore, the “Garden of the Sound” and the “Garden of the Tide” will extend the park into the water, highlighting another dominant feature of this region.

The saltwater shoreline is one of the mildest (although not warmest) climatic zones of the Pacific Northwest. Coupled with constant wind and water-induced erosion, the plant community is broadly diverse and unique. Shifting sand, grasses and salt-tolerant plants dress this sun-soaked landscape.

The tidal garden will feature kelp, algae and other intertidal zone plants that are revealed and concealed with the changing tides. The “Garden of the Tide” will depict tidal events, including lunar influences, and establish important marine habitat. The sounds of a thriving marine environment will connect people to the larger context of the park as well.

The interstitial spaces between these gardens are landscapes of grass and meadows. The lawns will feature low maintenance, native compatible, turf-forming grasses. Some of these species will also be a part of the meadow which may be mowed more frequently to enhance grasses or less frequently to encourage the wild flowers. The meadow landscape will accommodate changing uses, including future earthworks and other art installations.

One might look at the sequence of gardens as a timeline. The “Garden of the Ancient” stretches back to prehistoric times and pre-European contact to this region. It predates written language and represents the fascination we have with our past.

The “Garden of the City” is contemporary, representing a garden which respectfully questions control over nature. In this garden we are contemplating our day-to-day existence.

The “Garden of the Sound” and the “Garden of the Tide” are in many ways a place where we respect our ever-changing lives through the shifting sands, predictable tides and unknown universe of the seas.

But all of these thoughts and layers are not intended to prescribe a way in which a person may see the sculpture park. As with any art, what is experienced will be from the eye of the beholder.

The settings created by these landscapes will elicit responses from artists, who will be producing content for the park, from large works to subtle time-based pieces. The design of the Olympic Sculpture Park addresses ever-changing views of the role of a park in the city and art in the landscape.

The relationship of art, landscape and architecture — initially questioned in the 1970s — is being examined again here in Seattle, with a renewed enthusiasm and focus. Through these layers of meaning and process, a new park will emerge.

Charles Anderson is president of Charles Anderson Landscape Architecture.

Other Stories:

- Another scenic century

- Weaving stories into a living corridor

- Telling the story in the land

- Landscape architects adapt to changing world

- Seattle’s best outdoor spaces

- To stand at the edge of the sea

- Transportation and landscape design

- Growing urban oases

- Volunteers build community

- Celebrating sustainable water systems

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.