Surveys

DJC.COM

April 22, 2004

What is your landscape telling you?

The Portico Group

I'm fairly new to the field of landscape design, having spent some 20 years developing what one might consider traditional interpretive exhibits for cultural, natural and science museums.

Illustration by Bill Hacker

Traveler’s Rest State Park in Montana will let visitors explore how the future of Native Americans in the West was changed. |

As an interpretive exhibit designer, I have come to use this as my definition of interpretation: “An educational activity which aims to reveal meanings and relationships through the use of original objects, by first hand experience, and by illustrative media, rather than simply to communicate fact.” Or better stated, “Interpretation is the revelation of a larger truth that lies behind any statement of fact.”

Both of these quotes are by Freeman Tilden from his 1957 book “Interpreting Our Heritage,” written for the National Park Service. It is from this point of view I work with my landscape architecture colleagues at The Portico Group and it is the basis for our approach to the following projects.

A living museum and public park

A couple of Saturdays ago, I joined one of those landscape architects on a field trip to the Washington Park Arboretum in Seattle, where Dr. John Wott, director of the arboretum and our client, led a tour from the visitor center along Azalea Way to the Pinetum.

The arboretum describes itself as a living museum of woody plants and a public park. However, for most visitors, it is simply a visit to a public park. A place to stroll, to jog or just ponder a change of season — for rejuvenation — and this is great, just what a park should do. I doubt the idea that it is a museum ever crosses their mind.

But, the arboretum is a historic artifact, and a reminder of the classic landscape principals developed by the Olmsted family of landscape architects.

So how do we reveal the larger truth about an existing place — that there is a biological plan to the arrangement of trees, that the views are intended and revealed by paths that are designed to manipulate the visitors' points of view, and that the cultural history of the arboretum reflects the booms and busts of this Emerald City?

We start with researching the facts, coming to understand the glaciated geology that formed the arboretum's valley and valley side slopes; the evolution of the Olmsted Brothers' original planting plans and how the collection today references similar climates around the world. As for the question about interpreting the landscape and revealing this truth, as Freeman Tilden would tell you, the best interpretive device is a walk with Wott, a scientist who clearly knows the arboretum and more importantly loves it.

Wonderment with a message

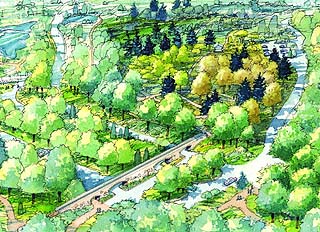

Illustration by Scott Taylor

The latest master plan for Seattle’s Washington Park Arboretum addresses the need to reestablish plantings. A future footbridge will provide

a direct connection from Madrona Terrace to the Japanese Garden and

Washington Park Playfield. |

“Where is the Wonder? I Wonder,” is the title of a 2003 article in Public Garden Magazine by Iain Robertson. Robertson writes: “...let me propose that fundamentally, conservatories should be in the business of eliciting wonder. And what, you will ask, do you mean by that? Which, after a stunned pause, you might continue with, you mean you want us to invest all that money and effort into building and maintaining our conservatory only to elicit wonder? Wonderful!”

Later in the same article, Robertson challenges the reader to decide if wonder alone is enough: “Will they (conservatories) become quaint anachronisms in a class with objects that one might encounter at a museum, or potent conveyors of vital messages for our society? Is it too much to ask them to be the latter? I don't think so.”

At the Buffalo and Erie County Botanical Garden Conservatory in New York state, we intend to accomplish both, create the wonder and convey a vital message.

The conservatory was established in the mid-1890s with a collection of plants primarily from Florida, Central and South America, exotic for this Victorian period.

As a result of our recently completed master plan, the collection organization has extended this snowbird flight from Buffalo south, circumnavigating a similar longitude around the globe. Several of the environments highlighted along this Buffalo Meridian are included in Conservation International's Biodiversity Hotspots, at www.biodiversityhotspots.org.

The interpretive approach to comparing and contrasting Buffalo with other places enables the conservatory to “make places” of wonder, where the visitor can be immersed in the sight, smells and texture of different environments. But it also enables us to describe the diversity, adaptation, ecosystems, climate, habitat and economics of these places.

For instance, in Florida, the visitor's first stop on the tour, they're immersed in a natural Everglades environment and learn about the agricultural “invasives” that have come to displace much of what was once there.

Just as with the Washington Park Arboretum, the foundation for such an approach is content research. Determining which habitats can be replicated for that sense of wonder, and therefore which plants can be used to illustrate important aspects of adaptation and reproduction.

As for revealing the wonder of these “made places,” we are incorporating a “green panel” system into the planting plan that blends with the overall ambiance of each gallery. We are expanding on this basic information using a touch-screen audio-visual program for self-directed learning and garden carts for docent-led presentations.

A site reveals itself

Tmsmlí is “no salmon” in Salish, their name for Lolo Creek located outside of Lolo, Mont. On Sept. 9, 1805, a Salish Indian named Old Toby guided Lewis and Clark to this place. The expedition, exhausted and with their supplies low, came to name this place Travelers Rest.

Travelers Rest encampment is located along Lolo Creek, close to where it joins the Bitterroot River, at the western edge of the state, and has historically been a crossroads for nomadic Native American tribes following seasonal resources. At this place, the different nations came together to trade, so it is understandable that Old Toby would guide Lewis and Clark here to rest.

So how do we reveal such a place, somewhat off the beaten track and in what is now a farmer's field? Well, we had to find it first. The original location of Lewis and Clark's encampment was initially sited based on Lewis' celestial observations and notes in his journal. Since then it has been determined that Lewis' observations were all off a bit, so with recalculated bearings and additional archaeological research, the true location was revealed and confirmed through materials they left behind. This research confirmed the location and the United States' history of the site but not its greater significance.

It was the result of our working with tribal representatives in the community that enabled the telling of the greater story — that at this location the future of Native Americans in the West changed forever.

The Native American hunter-gatherer stewardship of the land would be eclipsed by European American settlement. The design for the site reflects the “crossroad” history of the site. On one side of Lolo Creek, the design makes use of the existing farmstead as an education and administration area that provides access to and protection of the Lewis and Clark encampment site.

Crossing the creek, the visitor follows natural animal trails to the Native American Story Circle. This open field is laid out for presentations and historic recreations. Throughout the site, traditional interpretive materials are kept low key and incorporated into the natural setting. Beyond this, the visitor is free to imagine what is was like in 1805, and let the site reveal itself.

Getting back to Tilden's quote, “Interpretation is the revelation of a larger truth that lies behind any statement of fact,” to interpret a place, we first have to know the facts. We have to research the cultural and natural history, and study the community it serves, by consuming all the information we can about the place.

Revealing or making a place isn't choosing a theme or a look — the revelation comes from understanding how those pieces of information, the content, are used to drive all aspects of the design. This is what I tell my colleagues.

Norman Paul Stromdahl is an interpretive exhibit designer for The Portico Group in Seattle.

Other Stories:

- Gardeners go trowel to trowel in contest

- Art meets Frisbees in north Seattle park

- Seattle's big chance to reconnect the waterfront

- Keeping runoff out of sight, but still in mind

- Ecological restoration goes beyond trees and shrubs

- Amgen unwraps the landscape at Helix

- Landscape designers promote active lifestyles

- Low-allergen landscapes nothing to sneeze at

- The do's and don'ts of planting new trees

- Shared streets can provide open space, too

- Landscape connects rivers and cultures

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.