Surveys

DJC.COM

June 28, 2007

Tribe’s waste plant doesn’t raise a big stink

Special to the Journal

Photos by Terry Stephens

Processed water is conveyed through pipes from Tulalip Tribes’ waste treatment plant to irrigation areas and a pilot wetland project where plant growth is being studied. |

“We’re looking at forest irrigation, wetlands development and even a new biosolids fertilizer project that would produce a product from the plant,” said Lukas Reyes, utility superintendent for Quil Ceda Village Utilities & Environmental Services department. “There’s no real odor from the plant, except for smelling like clean dirt.”

Environmental scientists from the University of Washington are studying the test irrigation areas near the facility to evaluate the impact of the facility’s cleaned wastewater on plant growth and related issues. Studies of the wetlands areas also will determine if the water is beneficial for enhancing salmon spawning.

“Once the pilot programs are finished, we’ll expand to a larger site on the old Boeing test site. One of the major uses of the plant’s clean water will be for irrigation, including the landscaping around the casino,” he said.

Meanwhile, the facility continues to do what it was designed to do: process all of the wastewater received from Quil Ceda Village’s casino, retail centers and offices. The plant will also treat all of the wastewater from the 12-story, $33 million Tulalip Casino Resort Hotel when it opens in early 2008.

The treatment plant was the second of its kind to open in the Pacific Northwest, soon after one in Oregon that’s used primarily for golf course irrigation. But the Tulalip plant remains one of the largest membrane technology plants in the Americas and still has capacity to expand as Quil Ceda Village grows.

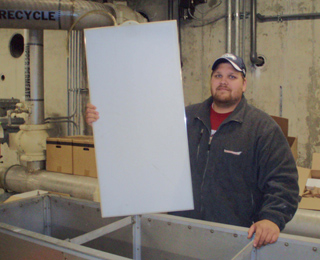

Lukas Reyes, utilities superintendent, holds one of 400 micro-filter membrane panels used to process up to 250,000 gallons of wastewater a day. |

When tribal leaders were seeking a design for their on-reservation treatment facility, they discovered Kubota had been working on a high-tech filtering system for wastewater since 1988. A decade later, the world’s first membrane bio-reactor (MBR) filtering system started up in England. That was the facility that John McCoy, state legislator and Quil Ceda Village general manager, toured with others in the tribe as part of their in-depth study of the membrane technology.

“The Japanese system uses large membranes to trap air in the system, allowing a higher concentration of ‘bugs’ to breakdown waste products,” McCoy said, describing it as an odorless system that produces less sludge and purer water in a much smaller space than comparable systems requiring large settling ponds. After screening out solids, the wastewater is aerated, filtered multiple times and disinfected with ultraviolet light before being discharged into surrounding fields.

Like other treatment plants, microscopic organisms are used to treat the wastewater. However, the MBR system’s 400 membrane plates filter the biological mixture, retaining the organisms as water flows through the membrane. As a result, three to five times as many organisms are used compared to traditional plants, allowing more treatment in a much smaller facility.

“We’ve been using those plates since the plant opened four years ago without having to replace any of them,” McCoy said.

After two years of construction, the plant began operating on the opening day of the Tulalip Casino, in June 2003. If the plant hadn’t worked as anticipated, the casino would have remained closed. But careful research, planning and construction assured the tribe it had bet on the right treatment solution for the huge facility.

After flowing through several membranes and other treatment processes, wastewater goes from muddy, left, to drinkable. |

Even though the technology was Japanese, the Tulalip facility’s final engineering design was thoroughly Tulalip.

“All we did was buy the membrane boards from the Japanese. Then we worked with Parametrix, a Sumner firm with a Bellevue office, on the design and with Harbor Pacific Contractors of Woodinville on the construction to build a plant that would suit our needs,” Reyes said.

Presently, the plant is processing around 250,000 gallons a day with one filtering tank. Using two of the four existing tanks would treat 800,000 gallons daily and all four would process almost 2 million a day. Provisions have been made to double the size of the building to boost the cleansing capacity to 4 million gallons per day, Reyes said.

In the control room, developed especially for the Tulalip facility, Parametrix created a touch-screen computerized system that tells Reyes at a glance exactly what’s happening in the plant, from the flow of the waste streams to levels of oxygen, nitrates and nitrites and how the pumps and mechanical system is functioning.

“You’ve got to know your biology to keep the system in balance. Once you do, then it’s a pretty simple operation that we can even monitor and adjust remotely, in case we’re off the site or even out of town,” Reyes said.

Overall, the performance of the plant, located a few hundred yards west of Quil Ceda Village, has more than satisfied the Tulalip Tribes’ goals and it’s still attracting attention around the world.

“We have the biggest and longest operating MBR plant in the country and we regularly get visitors for tours, including environmentalists and wastewater plant officials from many places, including Australia and Japan,” said Reyes, who has been on the site from the first day of the project. “Because we planned ahead to build it far beyond the immediate capacity we needed, we’re prepared for future growth at Quil Ceda Village.”

Terry Stephens is a freelance writer based in Arlington. He can be reached by e-mail at features@gte.net.

Other Stories:

- Cleaning up stormwater runoff on freeways

- New Seattle hotel to marry luxury with green

- Lakehaven solves water woes with ASR

- Treating rural wastewater is a daunting task

- The Emerald City’s tourist industry turns green

- Are nanomaterials another environmental worry?

- When BMPs can’t meet stormwater permit rules

- Contaminated site? Let Mother Nature help

- Why integrated design is off to a slow start

- Study your options when banking or reserving wetlands

- Developers must dodge newly discovered fault hazards

- A solution to our dwindling water supply lies below

- What to know when buying a contaminated site

- Blending a new community into the environment

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.