Urban Development

DJC.com

Next >

Back <

With landscaping,

density can start to grow on you

Neighborhoods of uncommon appeal can be created when architecture and landscape architecture are harnessed to a sympathetic value system.

By BARBARA OAKROCK

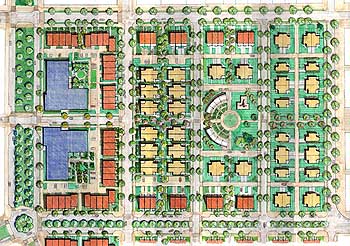

GGLO

The past 20 years of urbanization in American cities has greatly reduced expectations about what people will have to call home in the city. And the perception is that density is the culprit. But density can and should be used as a tool with which to sculpt "place" from the canvas of the city. And neighborhoods of uncommon appeal can be created when the disciplines of architecture and landscape architecture are harnessed to a sympathetic value system.

|

In Seattle, public housing renewal has emerged as an unlikely vehicle for fresh collaboration between the disciplines. Fueled by the Department of Housing and Urban Development grant program called Hope VI, which elevates neotraditional or "new urbanist" principles to the level of an outright requirement, three former public housing villages are being reconfigured and rebuilt. In the process, design teams have dedicated themselves to remaking whole Seattle neighborhoods according to a set of principles that consider density a positive attribute.

Among the basic values that contribute positively to the density picture are:

- A central focus for sites and neighborhoods scaled for everyday use. Public space captured by buildings should be scaled carefully. For example, a ratio of 2 or 3 times the surrounding building height to plaza width is comfortable on the ground.

- A clear and strollable street network. When streets connect logically, with comfortable sidewalks, shade trees and a minimum of garages, people will walk.

- Slowed traffic and tamed parking. For neighborhood streets, smaller is better. Where garages exist, parking permitted on one side only gives the streets back to people on foot.

- A diversity of dwellings within blocks and uses within buildings. By varying lot size, building type, tenant and designer, the pleasant texture of the American small-town street is re-created. The commitment to do this by the project’s promoters is always well-rewarded.

- Great streets and street facades. Every street, from alley to boulevard, has a role to play in designing for density. The ratio of street width to building height works well for people on the ground at roughly 2-to-1. This means that a 24-foot street with 10-foot sidewalks and 15-foot front yards would work best with buildings about 40 feet high.

- A principled and buildable approach to urban ecology. Through a design approach of many small changes, we have a chance to turn the corner slowly but steadily on resource depletion. Design, which demonstrates big ideas in a small way, can make a meaningful contribution. Rainwater cisterns for summer watering are a simple example.

- A rich patina of living materials. There is no substitute for the delight of rustling leaves and the scent of growing plants. The requirements of the landscape code should be understood as a point of departure for providing much more.

While these fundamentals are widely accepted, they are rarely accomplished. Economics, regulations, market perceptions, site program and even site geometry can get in the way—and too often landscape architects are late to the table.

Holly Park, Rainier Vista, Roxbury House and High Point Village are benefiting from well-integrated design teams. At New Holly the collaboration enabled the designers to shift the grid to save trees, create pocket parks and a system of residents’ gardens. In the new master plan for High Point Village, GGLO’s in-house team of architects and landscape architects is approaching the redesign together. The master concept plan is organized by a greenway arching across the site with the densest housing and service buildings on its edge. This 60-foot-wide linear open space within the street would provide a safe, defensible street park for many forms of recreation. With a 120-foot street right-of-way and 50-foot-high buildings, it’s proportioned for people.

By setting each block length and depth for specific housing typologies, the plan capitalizes on the streetscape and open space character that best suits the building type. The design thus offers a subtle departure from the surrounding wallpaper of streets. As the building height and density decreases from 30 or 40 units per acre to six or 10, the greenways and streets become tighter. In a neighborhood where large deserted parks are considered frightening, the greenways will provide a usable alternative, right outside of everyone’s front door. With continuous street facades, they will be interesting and lively.

Carefully designed public housing is teaching once again that when architecture and surrounding spaces—streets, squares, open-space—are formed together, they become the positive and negative aspects of the same successful design. Very close collaboration between architecture and landscape architecture is the key.

Barbara Oakrock joined GGLO Architects to create an in-house group of landscape architects and planners.

Top | Back | Urban Development | DJC.com Copyright ©1995-2000 Seattle Daily Journal and djc.com.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.