Surveys

DJC.COM

November 18, 2004

Skinner Building gets a seismic skeleton

Special to the Journal

Images courtesy of Burgess Weaver Design Group

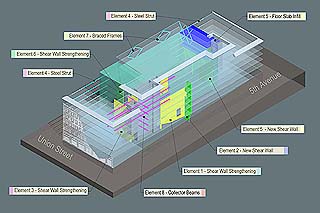

Shear walls, struts, brace frames, collector beams and slabs were strategically placed inside the Skinner Building to prepare it for Seattle’s next major earthquake. Click here for a larger view.

|

The value of interdisciplinary teamwork among architects, engineers and contractors on complex construction projects was proven once again in the recent $11 million seismic upgrade of Seattle's Skinner Building that houses the historic 5th Avenue Theatre.

In the aftermath of the 6.8-magnitude Nisqually earthquake in 2001, the 75-year-old structure was found to be intact, despite the quake's estimated $2 billion damage throughout Western Washington.

But Unico Properties, the management company for the Skinner Building and other properties on the University of Washington's 11-acre Metropolitan Tract, was shaken worse. Its executives didn't want to take a chance that a future quake would severely damage the building that also is home to a number of retailers, seven floors of offices and the entrance to the underground pedestrian concourse that links the Skinner Building to Union Square and Rainier Square.

In March 2002, Seattle's Burgess Weaver Design Group began working with Turner Construction and Magnusson Klemencic Associates to design the project. Retrofit work that started in January 2003 was finished last June and $750,000 under budget, according to Irma Dore, Unico's senior construction manager on the project.

Challenges

Protecting the 203,000-square-foot structure from quakes proved to be a challenging task.

| Skinner facts |

|

Location:

1326 Fifth Ave., Seattle Gross space: 203,872 square feet Cost: $11 million, guaranteed maximum Construction: January 2003-June 2004 Owner: University of Washington Building manager: Unico Properties Architect/interior architect: Burgess Weaver Design Group Structural engineer: Magnusson Klemencic Mechanical engineer: ACCO Engineered Systems Electrical engineer: VECA Electric & Communications General contractor: Turner Construction Co. |

Immediate challenges were found in the building's incomplete existing drawings. The plans were flawed, at times bearing little resemblance to what workers actually found inside.

Work crews continually dealt with surprises as they worked on each phase of shoring up the structure, often encountering interior remodeling changes and utility systems that had been modified over the decades.

Also, the project team had to work around the theater's open space, an area that extended up through six floors, creating a huge void in the core of the building. The team decided to anchor the rest of the building to the four-sided concrete box that framed the theater. Work included adding a 6- to 8-inch-thick layer of concrete on the theater's walls to provide a stronger and more efficient path for lateral pressures from earthquakes.

Keeping it 'live'

But aside from solving construction issues, the greatest impact on the work was "keeping the building live" during construction, said Tim Charoni, senior project manager for Turner's Special Projects Division during the pre-construction phase.

"We had to work around everyone's business hours," Charoni said. "With a mix of offices, retail stores and the theater's show schedules, adding up all of their 'open' hours didn't leave much time for us to work. It was often after midnight before we could begin. We worked that way for a year and a half," he said.

Steel bracing was used in areas such as window walls.

|

In an orchestrated operation — comparable in many ways to a medical team reinforcing the skeleton of a living person — a team of contractors surgically inserted steel bracing, concrete shear walls and concrete collector beams, working primarily after business and theater hours.

More than 1,200 yards of cast-in-place concrete was pumped into the structure for new shear walls and collector elements. Each night, as much as 60 yards of concrete passed through 250 feet of hose from trucks at the street level to pouring locations throughout the building. A fast cure rate allowed shoring to be removed within three to four days.

Most concrete work was done at night so that tenants were not interrupted. Concrete was pumped through 250 feet of hose from Fifth Avenue.

|

Existing shear walls and columns were strengthened wherever possible in the building, new cast-in-place concrete shear walls were added in many places, steel-braced frames were installed at the upper levels where possible. Concrete collector beams were attached to the bottom sides of existing floor slabs to improve connectivity.

The light courts formed by the wings of the E-shaped building were connected back to the main building, either through infilling selected areas with concrete slab or by providing steel drag struts at the building's exterior across the open courts.

A team effort

"It was our teamwork that made things come together," said Charoni. "The architects came up with concepts, then we'd go in the building to see if it would fit. If it didn't, we'd come out and everyone would shift gears (for a new approach). If they had been rigid (in their thinking) it wouldn't have worked. Teamwork was the only way to coordinate everything and keep the building live for the tenants."

"The teamwork was the key to our success," agreed Casey Caughie, Magnusson Klemencic's managing principal on the project. "We worked closely with the architect, contractor and owner because so much flexibility was needed for the work itself and adjusting to tenant schedules. The full team's input was required daily. The seismic upgrade was driving the project but it was invaluable to have knowledgeable architects on board to address the many issues that came up, from life safety to the challenges of working on an occupied building."

The exterior of the 75-year-old building retains its original look after $11 million in seismic improvements.

|

Each morning, for instance, offices and businesses opened their doors to find their work areas swept clean and "walls" of plastic shielding the prior night's construction work. The whole process was so well structured that many tenants later said they didn't realize the scope of the work going on throughout the building.

"It took an amazing amount of collaboration," said Dore. "Total costs were around $11 million, but it still came in $750,000 under budget."

"The team dynamic was great," observed Henry Weaver, a principal with Burgee Weaver Design Group. "Unico is one of our larger clients and we've worked with Magnusson Klemencic and Turner on other projects, but not of this scale," he told news media earlier this year.

Burgess Weaver's Ryan Hitt, who worked with Jae-Hoon Na on the design team, said the project has attracted a lot of attention professionally.

Terry Stephens is a freelance writer based in Arlington. He can be reached by e-mail at features@gte.net.

Other Stories:

- A new Rx for emergency room design

- Preparing the next design pioneers

- A new tool for analyzing seismic hazards

- Don't sacrifice green design to 'value engineering'

- How buildings can help 'reforest' a city

- Opportunities abound in China for A/E firms

- What owners need to know about seismic design

- Unique design brings Boeing workers together

- Ready to go national with your design firm?

- A/E firms look to plastic for growth

- Waterlogged walls? New system will tell you

- Designers — beware of technology convergence

- A past blast: building the road to St. Helens

- Commissioning squeezes the best out of buildings

- Peering into the future of urban supermarkets

- Designers have lofty aspirations for housing

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.