Surveys

DJC.COM

November 18, 2004

How buildings can help 'reforest' a city

MKA

Gangnes

|

The United States Green Building Council's LEED rating system is doing great things to transform the way we look at building design from the building envelope inward. However, this system has done little to advance ecological site design, as it allows a building to receive high marks even if the new building site's performance is no better than the surface parking lot it replaced.

Most urban redevelopment projects are still replacing black-top with its ecological equivalent: roofs and hardscape.

Decades of urbanization carried out with little environmental sensitivity have left our downtowns among the most ecologically challenged places on earth. The seemingly insurmountable task of making sustainable site design headway is further complicated by the fact that each individual urban project generally involves developing a building that extends from property line to property line. These zero-lot-line projects have typically been perceived as having no site available upon which to apply sustainable site practices.

Redefining the project site

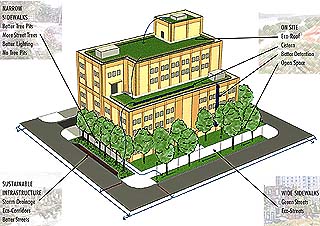

Image courtesy MKA

Urban greening deals with how the building and its site reduce environmental impacts, such as controlling stormwater runoff. Click here for a larger view.

|

The answer lies in taking a broader view of an urban project's site. Tremendous opportunities for sustainable site design emerge by considering the building as a means to provide site-like environmental benefits, and reconsidering an urban infill site as both the private parcel AND the adjacent public right of way. Considering the site and street frontage continuum as the total project site increases the area available for sustainable site design by up to 70 percent.

Some cities take note

Many cities have realized the contribution individual buildings can make to solving spiraling municipal storm water disposal, sewage treatment and air pollution mitigation challenges. Some are even rewarding developers who provide this type of greening in certain "troubled" areas in their urban core.

Seattle needs to follow suit.

In Portland, developers can get a building square-footage bonus by using green roofs in an area of the city with an overtaxed combined sewer. In Chicago, the city is pushing green roofs for their role in reducing the urban heat island effect that contributes to air pollution.

In Seattle? We're having a lot of "ongoing policy debates" in a variety of city agencies. Discussions on urban greening are being held, but independently by agency.

Seattle's Department of Planning and Development is discussing updating zoning requirements for open space and landscape buffers; the Department of Transportation is discussing revamping its Green Streets program; Seattle Public Utilities is discussing green roofs; and the Office of Sustainability and Environment is discussing adoption of the Kyoto Protocol.

Imagine the momentum if these discussions were integrated under a common initiative!

Forget the property lines

A program that encourages and rewards urban greening, regardless of which side of the property line, would integrate all the disparate policy debates and galvanize developers to build projects with good urban ecology. This strategy is based upon a few simple observations:

- Storm water management regulations are increasingly requiring sites to control runoff to pre-urbanization levels (i.e., that of a forest).

- These regulations apply to both private development and public infrastructure improvements.

- Most urban infill projects already use some degree of street frontage improvement, so considering this part of the site does not require growing the project.

- This larger site continuum makes it possible to implement green pursuits to which both the building project and streetscape contribute.

At Magnusson Klemencic Associates, we call this strategy "urban green."

Urban green is a collection of sustainable site design solutions that enable urban redevelopment projects to mimic natural ecological processes, rolling back the negative effects of urbanization.

Central to urban green is the notion that every bit of green counts. Every tree, shrub and sedum assists in managing and cooling runoff, providing habitat, lowering urban temperatures, creating oxygen and disposing of carbon dioxide. The green elements also provide social and aesthetic benefits.

Urban green enables integrated storm water management; using multiple ways to slow down and shed rainfall along its journey through a project. Rainfall first encounters a green roof where significant flow retardation occurs and evapotranspiration eliminates large quantities of runoff. Net runoff from the roof is then harvested in cisterns in or on the building for use in irrigation or building systems. Overflow from cisterns is handled by plant areas at the base of the building, in setbacks near the building and planting buffers in the street right of way. Lastly, sustainable public infrastructure directs net runoff to its historical receiving body.

Steps in the right direction

Several recent and upcoming projects are implementing parts of this strategy:

- The recently completed Alcyone Apartments in the Cascade neighborhood of South Lake Union has a rooftop garden irrigated with harvested rainwater, generous planting strips in lieu of customary tree pits, and even planting along the abutting alley.

- Across the street, when renovation is complete, Cascade Park will boast a creek element that is fed by the site and rooftops of adjacent building redevelopment projects, rather than a buried pipeline.

- The Olympic Sculpture Park planned near Myrtle Edwards Park will include a new storm water conveyance system that links together the three parcels comprising the park and directs all building and site runoff to Elliott Bay rather than to the combined sewer where it currently discharges.

Getting more green space

European cities are addressing urban greening with green space factors (GSFs). For instance, in order to develop a building in downtown Berlin, one must meet a minimum ecological standard that is measured by dividing the "ecologically effective surface areas" (green spaces) by the total site area.

GSF programs assign weighting factors to various types of greening (green on ground = 1.0, green roofs = 0.7, green walls = 0.5, etc.). A GSF target range from 0.3 to 0.6 is then mandated, depending on the type and size of development. The building code mandates the target, but the design team and developer can choose from a variety of treatments to meet the target.

Seattle should adopt a GSF program. Such a program need not be onerous to developers. By illustration, the Alcyone project as constructed (with its roof-top garden, plaza and sidewalk greening) would achieve a GSF of 0.1. Projects that just follow current open space and street tree zoning fall in the range of 0.01 to 0.05.

Participation in such a program could be voluntary. If a developer chooses to build a GSF building, he or she would get an incentive, championed by the city because of the overall greater good to the urban area. The incentive would offset any increased construction costs.

Next steps

Demonstrating and quantifying urban green elements and their benefits is essential to establishing a GSF program. MKA is starting a green roof demonstration project that could enable the Seattle design/permitting/policy community to move forward with green roofs.

Green roof test plots will be used to demonstrate how green roofs can reduce conventional stormwater management systems in buildings and ease the burden on city infrastructure systems while providing a myriad of other benefits. This evidence will help city agencies determine whether the city should provide incentives for projects that employ green roofs and begin the dialogue on an integrated urban greening program.

Drew A. Gangnes, PE, is director of civil engineering at Magnusson Klemencic Associates.

Other Stories:

- A new Rx for emergency room design

- Preparing the next design pioneers

- A new tool for analyzing seismic hazards

- Don't sacrifice green design to 'value engineering'

- Opportunities abound in China for A/E firms

- What owners need to know about seismic design

- Unique design brings Boeing workers together

- Ready to go national with your design firm?

- A/E firms look to plastic for growth

- Skinner Building gets a seismic skeleton

- Waterlogged walls? New system will tell you

- Designers — beware of technology convergence

- A past blast: building the road to St. Helens

- Commissioning squeezes the best out of buildings

- Peering into the future of urban supermarkets

- Designers have lofty aspirations for housing

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.