Surveys

DJC.COM

April 10, 2003

Telling the story in the land

J.A. Brennan Associates

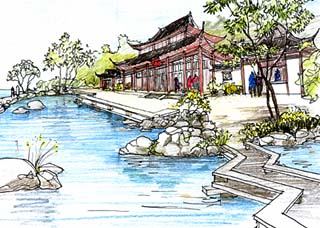

Rendering by Joe Wai Multi-cultural pavilion at Tacoma Chinese Garden and Reconciliation Park by J.A. Brennan Associates. |

Integrating culture into the landscape takes many forms.

Cultural landscapes may be defined as places where people explore human events and activities. Ecology, biology, beliefs, artistry or traditional customs all play a part.

Places as different as Italy’s Cinque Terra, a unique settlement in a steep and broken terrain, or Ecuador’s Galápagos Islands, a showcase of evolution, embody cultural landscapes.

Cultural landscape is about humans and nature. As cultural geographer Carl Sauer said in 1925, “The cultural landscape is fashioned from a natural landscape by a culture group. Culture is the agent, the natural area is the medium and the cultural landscape the result.”

Designing cultural landscapes typically involves revealing or interpreting historic events, protecting sensitive natural areas and creating places that bring people together to make personal connections.

The designer helps to tell the story of people’s connection to the land. The story is inherent in the design, and interpretive features express the story in creative ways. The landscape architect may work with the community to steward important cultural places and events.

Reconciling the past

A peaceful place can commemorate violent and tragic events.

The city of Tacoma’s Chinese Garden and Reconciliation Park, designed by J.A. Brennan Associates and sponsored by the city and the Tacoma Chinese Reconciliation Foundation, will offer an opportunity to remember and reconcile the tragic expulsion of Tacoma’s Chinese community.

In 1885, an economic depression fueled anti-immigrant feelings, racial bigotry and job fears, and this combination led Tacomans to evict Chinese immigrants from the community. The Chinese were forced to leave their homes, march to the railway station and board a train to Portland. Afterward, settlements were burned to the ground and Chinese were discouraged from settling in Tacoma until the 1920s.

The park will explore the lives of the Chinese sojourners who came to America in the mid-1800s to improve their lives. It will tell the story of expulsion and enable visitors to experience Chinese culture. The garden will create a place of peaceful reflection and the incentive to recall history, help people learn from the past and promote reconciliation.

The garden style is borrowed from the traditions of southeast China, the origin of many of the immigrants to Tacoma. Nature is imitated and abstracted in a dynamic layout of plants, paths, rocks, buildings and water elements. Modest architectural elements will promote familiarity with the lifestyle and settings of the early Chinese immigrants.

The entry and spatial sequences are carefully executed to create a variety of feelings and experiences. The spiral plan recalls a dance of the Chinese opera which symbolizes a journey.

The garden journey starts with a room that has “leak” windows, or screens that afford a glimpse into the garden itself. Visitors pass through a threshold and into a space with a mosaic and map of China. Then they climb upward to “Gold Mountain,” which refers to elements of a Chinese legend, brought to life in the American Gold Rush of the 19th century. The path features tools and durable goods that Chinese immigrants used on a daily basis.

From Gold Mountain, the path of the sojourner leads into a foreboding cut in the ground and a dark passage lined with menacing stones and tableaus of the expulsion from Tacoma.

In keeping with the wishes of the sponsors, the final theme of the park is celebration and reconciliation. From the dark passage, visitors rise up into a reflection room and a bright, open plaza to be used for community events.

Interpretive designer George Lim of Tangram Design served as a cultural consultant for the project. Architect Joe Wai brought to the team a solid understanding of the sojourners and the character of the built forms that would have been part of their everyday experience in China or America in the mid 1850s.

Lost heritage

Assisting tribes in recovering and rebuilding lost heritage is an important area of cultural landscape design. For California’s Wiyot tribe, that means telling the story of a crime and its tragic consequences.

In 1860, a group of settlers armed with hatchets, clubs and knives paddled to Indian Island, on California’s north coast, where they attacked and killed sleeping Wiyot men, women and children. Humboldt Water Resources and J.A. Brennan Associates are working with the Wiyot Tribe to make Indian Island a tribal center again by designing a cultural landscape that protects and preserves the sacred site.

Home to the ancient village of Tuluwat and traditional site of a ritual called the World Renewal Ceremony, the island’s middens, gravesites and rich history remains an important symbol for many Northern California Indians. In addition to interpretation of cultural heritage, restoration of Indian Island includes restoration of the native marsh and beach, and the construction of a ceremonial place that includes dance and tribal gathering areas, a traditional plank house, a restored dock and a kitchen.

Simple signage and architecture will convey an atmosphere of reverence and anticipation. Smoke from an entry fire will protect and purify visitors as they arrive. Outdoor spaces and rooms will convey a series of messages and feelings. Exploration of the site will lead to traditional ceremonial areas and areas for quiet reflection and healing.

The composition was crafted through meetings and interviews with tribal members who had researched the history of the site.

The Indian Island project represents an opportunity for the Wiyot community to reclaim its historic settlement, create a forum for the World Renewal Dance, restore links with other north coast tribes and educate tribal members. It will also help to minimize erosion of a shell midden at the site, and enhance fish and wildlife habitat.

Framing history and function

In a health care facility for the northern California Potowat tribe, a cultural landscape speaks the language of healing and respite. J.A. Brennan Associates worked with MulvannyG2 Architects to develop a master plan for the Potawat Tribes’ Health Village and Wellness Garden.

The educational, medicinal and cultural landscape responds to the traditions and rituals of six tribes in northern California. A redwood forest surrounds the village on three sides, with areas designed for tribal special events, dances, sweats, teaching and native plant gardening. The Health Village offers a courtyard for quiet introspection, a meandering stream and pond system for storm water treatment and views to the adjacent restored wetlands.

Concepts for the design were developed in a series of workshops with a cultural advisory group from the tribes.

By honoring Native American traditions and practices, designers were able to create a landscape of beauty and grace that is also functional. Extensive collaboration with tribal members has resulted in a final product that is a reflection of the values of the tribes.

Preseving, educating

Frequently, cultural landscapes focus on preserving the history of an area. An example of a landscape design that serves to educate visitors about an area’s past is the Upper Valley Plan (Wenatchee River) prepared for the Chelan County Public Utility District.

For the Upper Valley Plan, Tom Atkins, landscape architect and project manager, sees the cultural landscape in layers — agricultural, recreational and scenic — that define the character of the Wenatchee River Valley. Each layer offers interpretive, recreation and tourism opportunities.

Cultural considerations included expanding interpretive opportunities at the Chelan County Museum for the city of Cashmere developed by J.T. Atkins & Co. and J.A. Brennan Associates. Adjacent to the Wenatchee River, set in a park-like locale, the museum features a pioneer town with historical cabins, an orchard with interpretive signage telling the story of the valley’s agricultural history, an amphitheater, a waterwheel and irrigation ditches that demonstrate water at work.

The museum tells the story of man’s interaction with the natural environment. In addition to the museum site, the team identified other river access and interpretive sites along the river.

Federal Way’s Gethsemane Cemetery is exemplary of a landscape that reflects both Euro-American Catholic culture and Hispanic Catholic iconography. The cemetery, with its green grass, rolling hills and specimen tree landscape, is reminiscent of the Garden of Eden — a lush, green and safe place that Euro-American Catholic culture continually strives to reinvent.

Hispanic Catholicism is marked with its own iconography, such as the account of Mary appearing to the Aztecan Juan Diego atop Tepayac Hill in Guadalupe, Mexico, in 1531. Atop the hill, she convinces Juan of her holiness and persuades him to build a temple in her honor. The narrative of Mary, known as Our Lady of Guadalupe, is filled with crucial iconography that translates easily into landscape design; where objects such as snakes, roses and hilltops have been integrated into the cemetery’s landscape design in the form of pathways, plantings and landforms.

Designing cultural landscapes adds a richness to the vernacular. Designing with the past in mind, in an appropriate and sensitive way, exposes us to our history and to the riches culture offers.

Landscape architect Jim Brennan is principal of J.A. Brennan Associates. Christine Nack is a grant writer with the firm.

Other Stories:

- Another scenic century

- Weaving stories into a living corridor

- Landscape architects adapt to changing world

- Seattle’s best outdoor spaces

- To stand at the edge of the sea

- Transportation and landscape design

- Olympic Sculpture Park: a Northwest collage

- Growing urban oases

- Volunteers build community

- Celebrating sustainable water systems

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.