Surveys

DJC.COM

July 17, 2003

Sculpting a park out of a brownfield

Magnusson Klemencic Associates

Gangnes

|

Integrating restorative techniques into projects can correct environmental damage wrought by years of human intervention and restore native-like ecosystems, even in urban areas. A prime example is the work under way for the Seattle Art Museum’s Olympic Sculpture Park.

The project will transform a vacant brownfield site into a vibrant urban park. Multiple “precincts” for the outdoor viewing of sculpture will be created, each with their own unique identity.

Graphics courtesy of Magnusson Klemencic Associates

Olympic Sculpture Park will feature a 2,200-foot-long, Z-shaped path.

|

Through the placement of vast quantities of soil, Western Avenue will be reconnected to the shoreline, offering pedestrians safe passage over bustling Elliott Avenue and the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway tracks. Reconfiguration of the site will vitally link the Seattle Center with the central waterfront and Myrtle Edwards Park.

Architecturally, Olympic Sculpture Park’s design is brilliant. Weiss/Manfredi Architects’ use of a 2,200-foot-long, Z-shaped path will provide a gentle traverse of the park’s 8.5 acres, enabling easy access to all precincts within the park. Charles Anderson’s landscape design will boldly re-establish the prehuman landscape progression from upland to shoreline.

But there’s much more going on here than merely clever surface sculpting, reforestation and shoreline mitigation. Interweaving these achievements is a sustainable site engineering strategy that, when integrated with the architectural and landscape design, achieves a holistic, restored ecosystem.

Human intervention

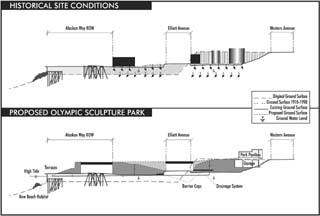

The sculpture park site has served as sculpting media for civil engineers multiple times over the years. The original shoreline of Elliott Bay meandered along the centerline of present-day Elliott Avenue and was comprised of small beach areas between densely forested bluffs. Shallow tidelands extended out from the shore, providing habitat for salmon and other wildlife. The site has undergone at least eight significant land alterations since the late 1800s, with each change accompanied by a dramatic environmental impact:

1. In the late 1800s, a planked trestle was constructed within the tidelands, creating a second waterfront. The trestle (which later became Alaskan Way) was heavily braced with riprap, creating a barrier that disrupted wave action and seawater migration.

2. Starting in 1905, fill was deposited behind the trestle, utilizing soil and demolished building materials from the Denny Regrade project. This created new, flat land with rail and water access, but it also buried 4 acres of tideland habitat.

3. Next, a seawall was constructed to create even more new land west of the trestle (the same seawall that exists today). Upon completion in 1934, 2 additional acres of prime waterfront real estate were created — but more than that amount of tidelands had been buried or disturbed.

4. Union Oil of California (Unocal) was one of several enterprises to utilize the strategic new shoreline area. The company began operating its Seattle Marketing Terminal in 1910, which by the early 1950s had grown to a 6-acre fuel storage complex on both sides of Elliott Avenue. To facilitate growth on the east side of Elliott, the original shoreline bluff — the last natural feature — was removed.

5. Myrtle Edwards Park, created in the 1960s, utilized soil, asphalt pavement and concrete debris excavated during the construction of Interstate 5. This fill was placed in the shallow tidelands west of the railroad lines, once more burying several acres of tideland habitat.

6. Unocal phased out operations at the site in the 1970s, but more than 60 years of fuel handling operations had left the soils and ground water severely contaminated.

7. The Unocal facility was demolished in the 1980s, and the vacant site was left to stew. Existing hot soils were unmitigated, leaving ground water in jeopardy.

8. In the 1990s, site remediation efforts began. Magnusson Klemencic assisted the environmental cleanup team by designing a means to remove tons of contaminated soil. At that time, a ground water cleansing system was also installed.

Restoring nature

And so we come to the ninth major land alteration on this site: the Olympic Sculpture Park. This time, a positive environmental agenda combined with a sustainable site engineering strategy will roll back the negative environmental impacts of the last 120 years.

The final cleanup. The strategy begins at the existing surface. Contaminated soils that could not be reached during the previous remediation efforts still underlie the site in some areas. When surface water is allowed to percolate through these pockets of soil, petroleum products can be carried into the ground water beneath. To stop this migration, barrier caps constructed of asphalt pavement and lean concrete — and in some areas the earth fill itself — will be placed on the site prior to fill activities.

Restoring the bluff. The importation of over 200,000 cubic yards of fill to rebuild the hillside will sculpt the site, in keeping with the architectural and landscape vision — and nature’s priorities. The massive fill operation will restore natural topography while respecting existing infrastructure. A continuous plane of ground will be created from Western Avenue to the seawall, restoring lost views to humans and wildlife, improving sun angles for plants and creating pedestrian access. Fifty thousand square feet of mechanically stabilized earth will hold back the fill, allowing Elliott Avenue and the BNSF rail lines to slice through this plane.

Bringing back the beach. A new beach and shoreline habitat area will be created at the junction of the sculpture park and Myrtle Edwards Park. By removing material placed 40 years ago, the original tidelands will be unearthed, and a sand beach will once again commingle with newly accessible tide pools. A series of terraces leading into this new shoreline area will be excavated behind the seawall. These terraces will provide an enticing habitat for a wide variety of marine creatures.

Runoff rollback. Ironically, this site immediately adjacent to the shoreline has not delivered storm drainage runoff to Elliott Bay for decades. Rather, rainfall landing on the site has been combined with sewage and conveyed to the West Point Sewage Plant 6 miles away.

The design for the sculpture park uses an intuitive approach of re-establishing storm water conveyance to Elliott Bay. It uses multiple means to roll back the runoff quantity from the site to a level approaching that prior to human intervention:

A great deal of environmental restoration will take place below ground at Olympic Sculpture Park.

Click here for a larger picture.

|

- Plantings of dense tree canopies, understory vegetation and ground covers will contribute to the retention of rainfall above the soil surface.

- A 3-foot-thick layer of engineered soil will further mitigate runoff. This special soil matrix is designed to reduce runoff quantity beyond that of normal soil.

- Escaping runoff will be conveyed to the waterfront area, where a controlled volume will be directed to the new shoreline terraces. This fresh water encourages a varied habitat, as migrating salmonids seek fresh water for spawning.

- The last bit of runoff will be directed into existing drains through the seawall. Dispersing the outfall to seven individual drains ensures that the rate and quantity of release has minimal impact to the shoreline.

-

When it opens in 2005, the Olympic Sculpture Park will be a vibrant example of urban life meeting natural beauty and artistic creativity. The park’s site design is not only an architectural and landscape marvel, but also a prime example of what can be accomplished through comprehensive sustainable healing.

Drew A. Gangnes, PE, is a principal at Magnusson Klemencic Associates and the firm’s director of civil engineering.

Other Stories:

- Battle over keeping dams rages on

- What’s your vision for Seattle’s future?

- Hat Island gets a drink from the sea

- Foss Waterway cleanup kicks into high gear

- Reclaimed water — a ‘new’ water supply

- LOTT dives into reclaimed water

- Clean air: saving our competitive advantage

- Europe points the way to sustainability

- Old maps handy for site investigations

- Planning for an environmental emergency

- Engineered logjams: salvation for salmon

- Pierce County maps where its rivers move

- Be prepared with a spill management plan

- Development can be beneficial to wetlands

- Check out properties with microbial surveys

- Charting a sustainable course for the Sound

- Water rights no longer a hidden asset

- The economics of sustainability

- Laying the path for responsible education

- Squeezing more out of renewable energy

- Controlling mosquitos and the environment

- Beavers back in force in the Seattle area

- Our future: no time or resources to waste

- Port Townsend dock promotes fish habitat

- Brownfields program is here to stay

- Master Builders teaches green homebuilding

- A salmon-friendly solution on the Snake

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us. - Battle over keeping dams rages on