DJC.COM

August 9, 2001

A blast from the past — modernism is back

Historic Seattle

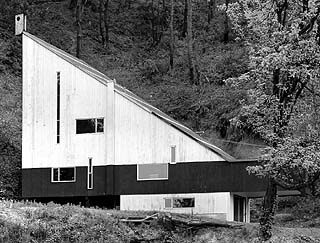

Photo courtesy of Historic Seattle Historic Seattle, a nonprofit, is restoring the Egan House, a modernist home at 1500 Lakeview Blvd. E. in Seattle. |

Subtle signs have emerged in Seattle and nationwide that there is a resurgence in all things modern. Increased interest and demand in modern-styled residences, the recent launch of numerous publications dedicated to the modern movement, and the increasing value and demand of mid-century modern furnishings and designs are all signals pointing to the renewal and rediscovery of the modern movement.

Modernism came to the United States in the early 1930s and to Seattle later that decade. Like other styles, it experienced a rise to triumph, a fall, and now a revival. Part of modernism’s strong appeal lies in its unique ability to evoke the future while also resonating in our recent past. We remember fondly the ubiquitous sleek shapes and streamlined designs from the 1950s and ‘60s, as do the many designers, publishers and architects forging the path to a renewed modern movement.

|

The qualities of modernism include a reference to the social idealism of the early 20th century, when mass production was sought to address the daily needs of people. The overall fundamental principles of modernism are few and broad — volume rather than mass, regularity rather than symmetry, transparency, elegant materials, technical perfection and fine proportions in place of applied ornament. A simplified characterization of the style is white flat walls with no extra applied decoration, severely cubic forms, large areas of glazing and open plans.

In Seattle, a volunteer organization has formed that recognizes modernism as a historic style that, like arts and crafts or art-deco, deserves to be appreciated and preserved. This group is DoCoMoMo.WeWa (Documentation and Conservation of buildings, sites and neighborhoods of the Modern Movement in Western Washington), a sub-committee of Historic Seattle, a local non-profit membership organization dedicated to architectural preservation.

DoCoMoMo is also an international organization with regional groups through out the U.S., Europe and South America. The mission of the Seattle chapter is to build public awareness of the significance of modernist buildings and structures in Western Washington through documentation, education and advocacy.

Andrew Phillips, an architect at Stickney Murphy Romine and founding DoCoMoMo.WeWa member states, “It is difficult to understand modernism as historic, mainly because of the movement’s intentional disregard for anything historical and its stark and simplistic style. However, this style had an important social and artistic mission and introduced some technological advances that are still relevant today. This is especially relevant to Seattle, as this style was used to promote an optimistic image of the future at the 1962 World’s Fair.”

The evidence of a modern resurgence in Western Washington is strong, according to DoCoMoMo.WeWa members, citing the popular rediscovery and the aesthetic pleasures of Northwest residences by early modern masters as an example. These are houses designed by architects Paul Hayden Kirk, Victor Steinbrueck, Roland Terry, John Sproule, Lionel Pries, Paul Thiry and Wendell Lovett. Further evidence of modernism’s revival is the recent nomination of seven modern-era Seattle Public Libraries and designation of branch facilities — The Northeast, Magnolia, and Lake City libraries — as city landmarks.

In an effort to educate and promote interest in modern architecture, DoCoMoMo and Historic Seattle recently presented a walking tour of modernism in Seattle’s Eastlake neighborhood.

A drawing from Victor Steinbrueck’s book “Cityscapes” of the Paul Hayden Kirk office building at Fairview and East Newton in Seattle. |

DoCoMoMo members extensively researched nine buildings on the tour, and attendees received a self-guided tour guide and admission to view five interiors. The buildings ranged from a private residence, the Egan House (1958) at 1500 Lakeview Blvd. E., presently owned and under restoration by Historic Seattle, to a small architectural office building by Paul Hayden Kirk (1960-61) at 2000 Minor Ave. E., to a large building, the original headquarters for Pacific Builder magazine and currently the headquarters for United Indians of All Tribes Foundation (1959-60) at 1945 Yale Place E. Also on this tour was the Asian Gallery/Architect’s Office Building (1953-61), designed and built by Gene Zema at 200 E. Boston St. This is an extraordinary, mixed-use complex expanding upon modernism with a specifically Northwest design.

DoCoMoMo.WeWa and Historic Seattle will continue to offer tours and programs for the general public to raise awareness of this important movement. The group meets monthly to discuss topics in modern architecture, design and preservation, and to arrange small tours of post-war era buildings for committee members. The committee is open to all members of Historic Seattle. For additional information, visit www.historicseattle.org and click on the volunteering link.

Despite this appreciation in modernism, interest alone isn’t enough to save the prime examples of modern architecture in the Northwest. As some important structural achievements (Kingdome, Seattle Central Library) in the area begin to disappear, it becomes even more important to identify other examples representing this era that can be successfully restored.

The architectural heritage of the modern movement is more at risk today than that of any other period due to its age, emerging problems with its innovative technology, changes in the original functions it was designed to shelter, and current development pressures. There is a pressing need for the documentation and the conservation of the best examples, and a greater understanding of modernism’s conceptual foundations, if we hope to share this striking architecture and aesthetic with future generations.

Alane Porter Griggs is a designer and writer for Historic Seattle. She also is a volunteer committee member of DoCoMoMo.WeWa.

Other Stories:

- The future is looking UP

- Urban form gets its roots from nature

- Downtown becomes a shopping mecca

- Earth-shaking discoveries impact design

- The scoop on infill development

- Infill problems? Get creative

- Rubbernecking leads urban retail revival

- Rx for Seattle’s growing pains: Collaboration

- DSA puts a downtown neighborhood on the ‘Edge’

- Public places — look between the buildings

- Getting the ball rolling with affordable housing

- Energizing Everett

- Urban development versus the public process

- Protecting views makes sense from every angle

- Urban development picture includes artists

- Pricing gridlock out of the market

- Retail? Start with the first floor

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.