DJC.COM

August 9, 2001

Retail? Start with the first floor

Special to the Journal

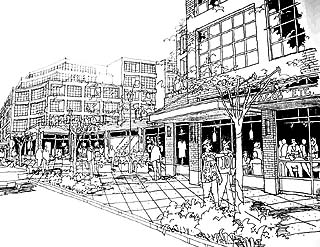

This concept for an urban project shows the viatality of residential living over first-floor retail. |

Shopping malls, restaurants and retail storefronts shape our urban experience. Unfortunately, first floor retail space in new residential or office buildings is too frequently neglected. As a result, developers, brokers, designers and the public miss out on an opportunity to enrich our urban spaces.

This article suggests how design decision makers can create better retail and it argues why they should.

The evidence is everywhere. Just take a stroll through the developing neighborhoods in this city and you’ll see isolated florist after barbershop after patron-less restaurant every time you cross a side street. Or even worse — a beauty salon on busy Highway 99.

These are not bad neighborhoods; these are great neighborhoods with huge potential. And yet we find a relentless parade of basically empty coffee shops hawking their wares to a daily handful of condo dwellers thrilled at the convenience but bemused at how much longer they can keep this particular outpost of “Seattle’s Best-Tully-Bucks” in business.

And (for better or worse) there is more to come. That is because common zoning areas give developers bonuses in exchange for first floor retail space and retail parking in their new projects — likely it’s economically unfeasible to proceed otherwise.

A study conducted by Val Thomas and Jennifer Potter for DCLU in 1998 found 47 percent of the retail space in 51 mixed-use projects surveyed was vacant (“Mixed Use Development Standard Study,” available from Seattle Department of Construction and Land Use, and the city’s Department of Neighborhoods).

Clearly from a public perspective, good retail only improves our shared urban environment. Picture a tenant mix that complements and enhances its surrounding neighborhood — providing context and integrity that complements the overall vision. Citizens can encourage better public spaces by taking part in public comment meetings. City decision makers who oversee these meetings can respond by requiring developers to build more functional and aesthetically pleasing retail space or by granting code variances.

Helpful variances might permit property owners to build smaller and less deep retail, or to avoid retail altogether if it is not suited to that particular site.

Developers want to create vital, profitable retail — not blight our streets with another vacant storefront or nail salon. But at the end of the day, they must consider first floor retail from a cost versus benefit perspective. Good retail does not come cheap. Street furniture, an attractive façade, parking (instead of more salable square footage), and the tenant whom they lease to (a coffee shop pays more than twice what a grocery store can) all impact project profitability.

Good retail is an investment. So what is the value in both dollars and goodwill for building better retail space?

The value of good first floor retail to developers is not just equal to the benefit it provides; it’s equal to the difference between its detriment and its benefit. Retail can:

- Enhance a project’s image, thus contributing to marketing and sales efforts. Simpson Housing project manager Scott Surdyke utilizes first floor retail to great effect at the upcoming high-end Neptune apartment project by leasing space to trendy retailers prospective tenants will identify with. Retail can be part of the story that brokers and leasing agents use to sell prospective tenants.

- Provide amenities that the developer cannot. For example, a gym would make a great retail addition to a condominium building that could otherwise not afford its own exercise facility.

- Rent for more, be vacant less and remain viable in a harsh economic climate.

- Satisfy the community’s interests — and that bodes well for new projects.

Local broker Ellen Mohl of Yates Wood, suggests that good retail space possesses desirable functional and aesthetic features, such as:

- Adequate, accessible parking. In congested urban areas and on large projects, easily-accessible parking may be a necessity for many tenants — it’s also required by the city of Seattle.

- Visible signage and flexible standards. However signs should also be uniform and attractive.

- An interesting, active façade. Landscaping, lighting, street furniture and canopies for weather protection all help.

- Reasonably deep retail bays (40-60 feet) that are divisible into many small pieces, or can be combined into larger ones. Big boxy spaces are hard to lease because they are in less demand in urban areas.

- Be well-suited to the demands of your desired tenant. For example, a restaurant space needs a grease vent plus adequate trash disposal facilities.

Developers do well to address these requirements. Just because the numbers work on paper doesn’t mean that the building works in reality. And, sometimes the compounded effect of retail mistakes is greater than their sum.

Unfortunately, all too often buildings are designed, scoped, specified, divvied up and approved before anyone from either the retail or brokerage community gets to offer their 5 cents worth.

Gene Silverberg, CEO of The Retail Group, a consulting firm involved in a number of local developments, understands the dynamic better than most.

“Architects protect the integrity of their buildings for good reason, it’s one of the things they are paid to do,” Silverberg said. “Likewise, the real estate brokers have a responsibility to their clients to make sure the development makes fiscal sense. But these factors, while a major part, are not the only things to consider.”

Retail design involves more than carving out rectangles on a plan; more than achieving ubiquity and complementary façade.

Perhaps most important of all, we must ask ourselves: Does it make sense? And not just financial, structural, functional or architectural sense, but does it make sense to the people who are going to use this space, to the local community and also to their visitors. Will they look at this component of the development and understand why it is here? Answer this and you will have taken the first step to defining the essence of designing consumer experiences that resonate.

The answer may be that the best retail space is no retail space at all. If retail does not fit with a particular site it should be avoided with a land use variance. Or, if the site is not conducive to another “Seattle’s Best-Tully-Bucks”, perhaps walk-up live/work style condominium space? Just such a variance was granted at developer David Zarett’s luxury condominium project across from Gasworks Park called the Northlake on Wallingford, and Triad Development’s neighboring Regatta condominium project.

Retail can be more than a burden or a token gesture put there to satisfy Seattle’s Land Use Code. The goal for any first floor retail project is to combine its retail and residential uses in a mutually complementary manner. These are true mixed-use buildings.

Christian Davies is executive creative director of The Retail Group whose current projects include new prototypes for bebe and Babies R Us.

Matt Holzemer develops condominium communities with Conner Homes Co., where he is working on a large mixed-use building in the Green Lake area.

Other Stories:

- The future is looking UP

- Downtown becomes a shopping mecca

- Earth-shaking discoveries impact design

- The scoop on infill development

- Infill problems? Get creative

- Rubbernecking leads urban retail revival

- Rx for Seattle’s growing pains: Collaboration

- DSA puts a downtown neighborhood on the ‘Edge’

- Public places — look between the buildings

- A blast from the past — modernism is back

- Getting the ball rolling with affordable housing

- Energizing Everett

- Urban development versus the public process

- Protecting views makes sense from every angle

- Urban development picture includes artists

- Pricing gridlock out of the market

- Urban form gets its roots from nature

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.