Surveys

DJC.COM

July 25, 2002

Getting back to basics with LEED

Skilling Ward Magnusson Barkshire

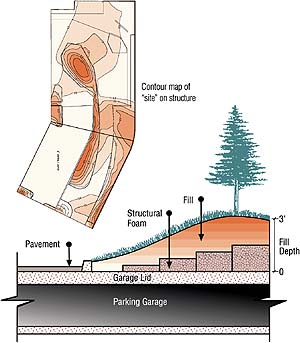

Images courtesy of Skilling Ward Magnusson Barkshire Advanced design techniques were used to nestle an underground parking garage into a hillside, then sculpt the lid’s surface while minimizing areas requiring “premium” load-carrying capacity. |

The Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating system has become the industry standard for gauging a design project’s sustainability or “green-ness.” However, a LEED-centric design can miss many green opportunities that fall outside the stringent LEED criteria.

A back-to-basics approach to site design can identify intuitive and simple solutions that are also environmentally responsible. Performing a sustainability audit along the way can then determine if those pursuits satisfy LEED credits as an added bonus.

The United States Green Building Council published the LEED rating system in 1999 in an effort to “develop a standard that improves the environmental and economic performance of commercial buildings...” LEED’s point system, which offers a maximum of up to 69 points for achieving prescriptive credits in six categories, has become the driving force behind incorporating sustainability into the design of all types of facilities, regardless of whether they are the commercial building project type originally envisioned by the LEED authors.

Applying LEED standards to all types of projects has many positives. In particular, it has increased the design community’s awareness of sustainability and green building practices. Many projects now begin discussing LEED expectations early in schematic design, and most consulting firms working in disciplines impacting a project’s LEED rating now sport their own proprietary LEED rating resources and checklists.

Moreover, LEED has been a valuable tool in breaking green design into pieces that people can get their arms around; the LEED categories themselves are great touchpoints for sustainability goal setting.

Shortcomings

One problem with the LEED method of sustainable design is that it can foster an all-or-nothing attitude toward this pursuit. LEED audits have become a common activity during schematic design. All too often, however, green design is abandoned entirely once this audit shows a project falling short of the number of points required for LEED certification.

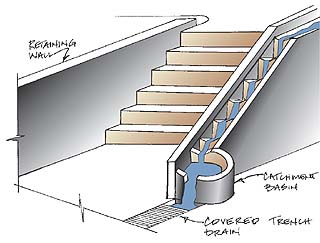

At the Bremerton Navy Hospital parking garage site, civil and mechanical systems were merged to route runoff through the structure, rather than around it. |

Many projects have the potential to incorporate remarkably sustainable design solutions that don’t fit into the defined LEED credits. Appropriately, the LEED system offers an “Innovation and Design Process” category to reward “out-of-the-LEED-box” thinking. However, these credits make up only a very small part of a LEED rating.

Finally, projects that are site-intensive with modest building facilities will find it impossible to garner enough LEED points to become certified. This is understandable, since LEED was framed around commercial building projects. However, site-intensive projects still look to LEED for sustainability credits and come up short. The concern is that if LEED rating is the only standard bearer for sustainable bragging rights, green design opportunities may be overlooked or ignored.

An environmentally responsible approach

In sustainable site design, looking at projects from the standpoint of environmental responsibility can help mitigate LEED frustrations. This approach simply asks at the outset of a project, “What sustainable design pursuits are available on this site?”

Once these pursuits are collaboratively identified and accepted by the project team, the remainder of the design and construction process is concerned with advancing those pursuits. The LEED rating system can be brought to bear anywhere within the project process, but is used truly as a score card rather than a guideline, allowing ideas to lead the way instead of the LEED checklist.

For example, early in the design of the recently completed Bremerton Navy Hospital expansion, it was determined that a water quality swale would be required for treating oily runoff from new roadways. The catch was that the new roadways were up-slope from the new hillside garage, while the site available for the 200-foot-long swale was down-slope.

The standard solution would be to run a civil pipeline around the structure and down the steep slope, yet a back-to-basics thought process led to the pursuit of a solution through the structure. A joint civil/mechanical collaboration produced an alternative, connecting runoff collected up-slope in a civil pipeline with the mechanical plumbing system at the face of the garage. The runoff was then plumbed through the building structure and exited the garage on the down-slope side, where it again became “civil” as it dumped into the swale.

This approach reduced the amount of piping required for the project and eliminated the need for trenching a storm drain line down a sensitive slope.

On the same project, an undulating grade on the structural lid of the garage was desired to make the garage disappear into the native hillside.

The normal approach would be to design the entire lid structure to support a maximum anticipated soil load. Civil grading design on both the finished surface and the lid structure itself dictated the structural geometry as a series of warped planes that approximated the surface grading above. This allowed both the earthwork design and the structural design to be optimized for the actual grading/loading conditions, versus a “maximum anticipated 3-foot depth.”

Both earth and reinforced concrete materials were saved in the process, resulting in a more sustainable and cost-effective design.

An educational opportunity

For an elementary school currently in design, storm water management facilities were identified early on by the design team as a potential educational opportunity. Rather than using a typical approach of large-scale underground tanks and supporting conveyance systems, a concept was developed for meeting much of the site’s storm water detention requirements via above ground cisterns. The cisterns store water that is then fed to children’s play devices, such as flumes and swales.

This “water stair” is one example of how nontraditional approaches to stormwater runoff control can provide site interest and educational opportunities.

|

This “micro-detention” approach avoids pumping systems and stores water where it is needed in a way that is educational, entertaining and environmentally friendly.

Another educational facility project in Seattle has a program goal of incorporating water into the site design to stimulate creative thought. Conventional ideas for creating a man-made stream were discussed early on; these required recirculating pumps and filtration systems.

An alternative concept has been developed that utilizes storm water from an existing public storm drain line running adjacent to the site and draining the watershed up-stream from the site. Diverting a portion of that water through a constructed stream will satisfy the program goal in a much more holistic and sustainable way. Water simply emerges on the site and runs through it, without the need for a recirculation system.

Back to basics

The green design elements described above would not reap a single LEED point, except perhaps an innovation credit. However, each is an example of a sustainable pursuit that responded to the question, “Is there a more environmentally responsible way to do this than the conventional approach?”

This approach requires a collaborative design team effort, since many sustainable design ideas will span design disciplines. Early identification of pursuits is key to this process, so that each discipline can plan their work accordingly. Keeping the green pursuits in the project is another important collaborative effort.

All too often, green pursuits are “value engineered” out of projects, based on inadequate understanding of the design. Including contractors in the design is therefore crucial; to ensure that cost comparisons consider all systems affected by a given green element (including life cycle costs) and to serve as a true partner when brainstorming construction techniques.

Considering sustainable design from a standpoint of environmental responsibility can uncover significant opportunities that might otherwise be overlooked. Commercial buildings and other facility types that are reasonably well covered by the LEED rating system can become even more sustainable through this approach.

Just as important, site-intensive projects — those that don’t mesh as well with the LEED system — can easily incorporate sustainable elements that are environmentally friendly and user appealing. These projects, which include parks, recreational areas and even transportation undertakings, often have a high public profile, offering an ideal opportunity to further the connection of community and environment.

Drew Gangnes, P.E., is a principal at Skilling Ward Magnusson Barkshire and leads the Civil Engineering Department. He takes a holistic approach to site design, to provide civil infrastructure in an intuitive manner, utilizing back-to-basics techniques wherever possible.

Other Stories:

- Water storage goes underground

- No more fuming at chemistry class

- Seattle LEEDs the nation in sustainable building

- New stormwater rules looming for contractors

- An incubator for cutting-edge power projects

- Linking up with the environment

- Designers find new life for old cardboard tubes

- EPA turns up the heat with temperature rules

- AGC teams with WSDOT for environment’s sake

- A wholistic look at engineering

- Toxic black mold — the next asbestos?

- Mold: Getting a grip on the fuzzy stuff

- A trail of mining waste turns into a trail of recreation

- A battery of energy information

- Managing stormwater in Pierce County

- New brownfields law comes with big changes

- ‘Green infrastructure’ puts Seattle on the map

- Detention ponds – all it takes is a little magic

- Ground zero for groundwater

- A pearl of a project on Oyster Creek

- BetterBricks program stacks up energy savings

- Shopping ‘green’

- Home Depot builds atop an old Oregon landfill

- Making clean water the green way

- Salmon in the city: Seattle restores fish habitat

- A funny thing happened on the way to the dump

- Reducing energy costs, post crisis

- Does best available science work for all buffers?

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.