|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Environment

| |

|

May 2, 2002

Smart planning begets smart lighting

Abacus Engineered Systems

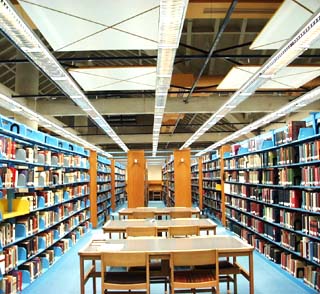

Courtesy of Abacus Engineered Systems Central Washington University Library uses a task-specific system designed for vertical illumination.

|

Such an approach can work to the detriment of energy conservation and sacrifice the visibility needs of the occupants. It’s this result that sparks conversations on how lighting systems need to be made more “sustainable.”

So, what is sustainable lighting design?

Sustainable lighting designs are much more than energy efficient. They are also resource efficient and satisfy the building occupants’ needs at all levels.

They are resource efficient in the sense that they either reuse existing materials like fixture housings (but not old, inefficient lamps and ballasts), or the designs use as few fixtures as possible, but still meet the requirements for the project.

Energy efficiency is a feature of sustainable design that is easily measured and quantified, but shouldn’t be confused with meeting the energy code. Truly sustainable designs consume about 50 percent of the allowable watts per square foot in current codes without tricks such as exempting certain lighting equipment.

Finally, a sustainable lighting design is one that will meet the needs of the building and the users for the life of the space. This means the light levels are appropriate, the controls are easily maintained and the maintenance of the system isn’t a huge annual capital expenditure for the building.

How are sustainable lighting designs achieved, then? Just follow the simple principal of “whole lighting design.”

Whole lighting design

Whole lighting design breaks down the pre-design analysis for lighting systems into four main categories: visibility, aesthetics, energy and technology. Failing to address any one of the four categories ultimately results in a design that will fail in one degree or another.

The first and most important step is to understand the visibility requirements for the space. To get a handle on this, the lighting designer needs to gather data on how the space will be used from the architect or owner. The goal is to find out what the occupants will need to see in different spaces and what they will be doing in them.

Central Washington University Library, for example, removed an indiscriminately placed lighting system and replaced it with a task-specific system designed for vertical illumination. The result was that library users could see the books on the stacks (a vertical task) more easily, while the library achieved a dramatic reduction in energy use and maintenance costs because it could remove lamps, ballasts and fixtures.

The visibility requirements for a space will dictate where and how much lighting needs to be applied. Oftentimes, it is found that once the task issues have been addressed, the ambient lighting becomes a byproduct of the task lighting, rather than the other way around.

Aesthetics

The second most important category of whole lighting design is aesthetics. Today, emotional responses to architecture and space can be greatly affected by the electric lighting system, and designers can become easily enveloped in creating the perfect aesthetic condition without regard to visibility, energy or the technology specified.

To address this issue, the design community needs to examine the foundations of our choices when it comes to aesthetics, and recognize those choices may be based in our culture’s fascination and participation in consumerism. Such cultural values often drive designers to add elements and light fixtures that are only necessary for aesthetics and subsequently consume additional energy and resources.

Sustainable lighting design, on the other hand, looks at how nature works and is often driven towards a heavier integration of daylighting in lieu of electric lighting to add drama and contrast to a space. In addition, daylighting not only provides a free source of light for buildings, it also provides something electric lighting never will: an actual view of the world outside the building.

The final two categories in whole lighting design — energy and technology — are often found to be byproducts of the first two. That is, once the stakeholders have addressed the visibility requirements and aesthetic needs for the space, they might find that limits of the energy code are not restrictive after all, and the choices in the technology and equipment that will be specified become pretty straightforward. However, in sustainable design, the designer should still scrutinize these two categories and make sure that the final design is not maintenance-, resource- and energy-intensive for the future owners.

More than green

As much as members of the architecture, design and construction community like to the create labels for their projects, sustainable lighting design should not have to be relegated to only “green” projects. Many benefits of sustainable lighting design exist for building users and the environment, regardless of project labels, in the forms of improved life cycle costs, improved productivity, reduced greenhouse gases and reduced resource extraction.

Of all the elements of sustainable architecture and design, sustainable lighting design is probably the least onerous to apply. All one has to do is understand the users’ needs, examine and possibly refocus aesthetics biases, strive to perform better than the energy code, and finally, create a design that is resource efficient and easily maintainable for years to come.

Ameé Quiriconi is an associate and lighting systems specialist at Abacus Engineered Systems.

Other Stories:

- When building green isn’t thinking green

- Sustainable design in the real world

- Why green buildings fatten your bottom line

- The future bodes well for green development