|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

1999 Construction & Equipment Forecast

|

|

Seattle tunnel builders face sand, gravel and `bull's liver'

By BRAD BROBERG Joe Gildner has a boring job. So why does he consider it a challenge? Because he's the project engineer for a pair of tunnels Sound Transit will bore beneath Beacon Hill and Portage Bay as part of its light-rail system. Together with a legion of consultants and contractors, Gildner will tackle a project fraught with unknowns - chiefly, what the heck's down there? Although extensive testing will give engineers a darn good idea of what to expect, they won't know for certain until they start digging. Even then, conditions can change with every foot they advance, from gravel to sand to the runny muck that engineers call "bull's liver" for its squishy consistency. Vic Oblas, a construction manager for Metro's downtown bus tunnel, compared the uncertainties of tunneling to "black magic." But Gildner remains undaunted. "It's just a matter of trying to determine how many variations we'll have to deal with," he said. "It's the kind of challenge we like to work with." The Sound Transit Board recently identified a preferred preliminary route for the light-rail line - dubbed Link - and its stations. Trains will travel on a combination of elevated, street-level and underground tracks between the University District, Tukwila and Sea-Tac Airport.

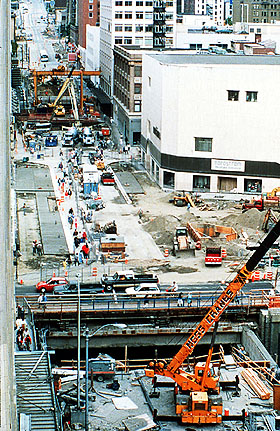

The longest of the new tunnels is the 4.2-mile north corridor shaft, which will pass under Portage Bay on its way between the University District and Capitol Hill. It will include four finished underground stations. The other tunnel is an 0.8-mile shaft under Beacon Hill that will include the shell for a possible future station. If all goes well, trains will chug through the tunnels in 2006. Right now, Sound Transit is working with Puget Sound Transit Consultants (PSTC) to complete preliminary engineering and conceptual designs for the tunnels. PSTC is a joint venture of three Seattle firms -- Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade Inc., BRW and ICF Kaiser. Nearly 30 subcontractors also are involved, said Dave Donatelli of Parsons Brinckerhoff, project manager for the PSTC team. Sound Transit has carved tunnel construction into several separate contracts - two or three for the north corridor and one for Beacon Hill. Requests for qualifications from design/build teams will start in March. After the final EIS is finished in August and the preferred route formally adopted, Sound Transit will award the first construction contract in the spring of 2000 - provided federal matching funds arrive as expected, said Gildner. The overall price tag could reach $600 million or more. Gildner expects no shortage of bidders - both from across the country and around the world. Besides building tunnels - or "mining and lining" - as Gildner calls it -- the project involves two other major components: the mechanical, electrical and finishing work; and installing the light-rail system itself. The tunnel construction contracts will cover some of that work, but other portions will be bid separately. The bus tunnel, which was under construction from 1986 until 1990, involved more than 20 separate contracts and hundreds of subcontractors, said Dan Williams, Metro spokesman. So far, PSTC has taken a smattering of soil samples. Now that the Sound Transit Board has identified a preferred preliminary alignment, engineers will zero in on the route and take hundreds of additional soil samples. Normally, engineers might also be able to rely on geological reports that were prepared when various buildings were constructed along the tunnel routes. However, since the tunnels will be so deep - between 180 and 230 feet - the value of that data is limited. In fact, the tunnels are so deep that passengers will use elevators, not escalators, to come and go from the stations. At this time, engineers believe they will be dealing with constantly changing soil - from clay to sand to rocks to muck - deposited by glacial flows thousands and thousands of years ago, said Gildner.

"The kinds of machines applicable here will have to take into account the variety we'll encounter," Gildner said. For instance, expecting muck below Portage Bay, the contractor most likely will employ a tunnel boring machine equipped to inject substances that stiffen the runny soil. "It's critical to stay on line and grade and support the face so we go forward and the machine does not get bogged down," said Gildner. Still, unless engineers drill enough test holes to turn the tunnel routes into pin cushions, there's always the potential for an unpleasant surprise. "You're not flying blind, you're working with the experience of past projects and with the geologic information you've collected," said Donatelli. "But you can't take a sample every foot of the way." The bus tunnel provided at least one example of what can happen when Mother Nature plays a trick. Oblas recalled how, with only 300 feet to go, the tunnel boring machines unexpectedly struck muck - a.k.a. bull's liver - and started drilling downward. The contractor had to sink a relief shaft and use alternative methods to finish the tunnel. As is customary, the guts of the tunnel boring machines were removed, but their protective shields remained entombed to become part of the tunnel walls. Tunnel boring machines are custom-built monsters. Their face is a rotating serrated plate up to 20 feet in diameter. Their head is a capsule where three or four workers guide the beast. Their tail, known as trailing gear, is the length of a football field and packs the hydraulic system and multiple electric motors that generate 3,500 horsepower or more. Conveyor belts carry the dirt from the face to the end of the trailing gear, where it is either dumped into mining cars or onto another conveyor stretching back to the tunnel portal. "Just think of the amount of hardware we're going to have underground," said Gildner. The machines make ponderous progress. On a good day, they crawl 30 feet, drilling slightly upward so any groundwater they encounter flows away. As they advance, they leave behind a liner to stabilize the tunnel walls. Gildner said the Sound Transit tunnels likely will employ a method in which the machines deposit pieces of concrete rings that workers bolt together. Gildner said the process resembles an assembly line, all the more reason why knowledge of the terrain ahead is vital to steady progress. Despite the size of the tunnel boring machines, Donatelli said no one above ground will have a clue they are chewing away below - other than the parade of trucks hauling dirt from the tunnel portals. Where will they take it? "Good question," said Gildner. "Do you know anybody who needs 1.5 million cubic yards?"

djc home | top | special issues index

|