|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Special Issues

April 20, 2000 Urban ecology, or expressing nature in the city In these landscapes, time and total transformation are part of the design

By CHARLES ANDERSON Parks and open spaces are often the only parts of our cities where we can experience, interact with, and learn from nature. So, it is crucial that the designs for these precious spaces maximize their value on a variety of levels. Traditional landscape restoration projects-particularly of wetland and environmentally sensitive areas-often focus exclusively on environmental processes. In urban areas, these places are sometimes designed to mimic nature and do not always reflect the influences of the context. These science-based designs follow a prescribed restoration composition or style. In many instances designers will go to great lengths to shape and control environmental processes instead of accepting these urban conditions as an opportunity to express a new "urban ecology".

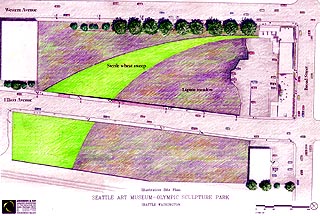

Sometimes the right balance between design and nature can be found in accepting a new landscape as a work in progress. The physical and cultural character of the site can evolve. Meadows become forests, structures are consumed by plants, ordered landscapes pattern themselves after site conditions. An elegant expressionist landscape design can give way to natural processes. In these evolving urban landscapes, the early stages are candidates for unusual and inventive designs. For instance, you might plant a circle of purple flowering perennials in a meadow, expecting the circle to change shape from year to year. There might be cedar seedlings in a large grove of alders in anticipation of a towering conifers. We have explored these concepts in numerous projects. Currently we are installing an interim "landscape" for the proposed Seattle Art Museum Sculpture Park (Olympic Park). Here we are imposing a great sweep of sterile wheat across a lupine meadow canvas. The sterile wheat is itself an anomaly for use in restoration projects. It is a highly cultivated plant that will act as a placeholder. The project is both a restoration expression and an art installation. This installation functions to restore the quality of the site ecologically as it nurtures the soil for future plantings, and aesthetically through a unique interim ecology.

At Pritchard Reserve, along south Lake Washington, the landforms, wetland zones, and paths will follow a fundamental goal of synthesizing ecology and art. Elevated viewing platforms, an amphitheater and wheelchair-accessible paths will bring people closer to communities of open-water and emergent wetland, scrub/shrub thickets and upland forest while consolidating areas of human disturbance and travel to a small portion of the site. Seasonal eye-catchers like the "Maple Cathedral," "Alder Gallery," "Swamp Lantern Cavern," and "Devil�s Club Crescent" are features intended to be artistically striking places, which also uphold the ecological integrity of the park. While the natural character of The Reserve will evolve during the lives of successive generations of visitors, these artistic messages will communicate growth and natural processes by visibly contrasting with or joining in the landscape as it changes.

For years, the nuclear cooling towers of Satsop Development Park, near Aberdeen, have stood like Easter Island effigies, rising above the surrounding forest. Their presence strikes a somewhat foreboding image to passers-by along the Olympic Loop Highway. The towers always generate great curiosity. Curiosity, coupled with the knowledge that this nuclear power plant will never be "fired up," makes the nearly 500-foot high towers-with an interior clear span opening which could easily encompass a football field-a hard to resist attraction. It is inside of one of these most impressive of structures where we seek to preserve a "new-clear" ecology. The tower houses a remarkable collection of plant communities that have adapted to the interior of the tower for Cooling Tower Park. When the park opens to the public this summer they will find a sort of mini-arboretum to stroll through. Just as we have chosen to preserve the industrial archeology of the great towers we have also recognized the unique richness of plant patterns and mosaics that are sheltered within. This too is a testament to the power of nature to act with us to transform most insane of endeavors.

Charles Anderson is a principal with Anderson & Ray.

| ||||||