DJC.COM

September 12, 2007

7 Engineering Wonders: Civil — Making the grade for a road separation

Berger/ABAM

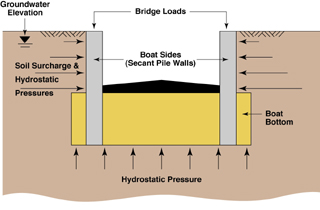

Images courtesy of Berger/ABAM A boat-like structure was built in the ground to support the rail crossing above while providing a base in the site’s weak and watery soils. |

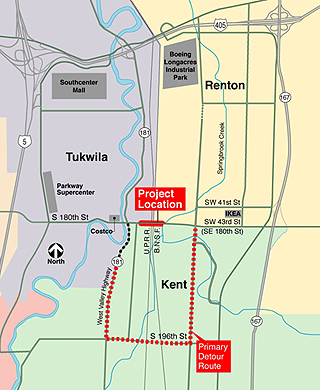

The Southcenter area of Tukwila, Renton and Kent has some of Seattle’s biggest retailers: Ikea, Home Depot, Costco, Southcenter Mall and Pavilion Shopping Center. Shoppers and employees access these stores using South 180th Street, a four-lane arterial. Or rather, until 2003, they tried using South 180th Street. Sixty times every day, 15 minutes plus each time, freight and passenger trains crossed the road and halted cars, delaying more than 40,000 drivers.

Everyone wanted to reduce driving times, increase revenues, reduce emergency response times, and eliminate potential death and injury from train and car collisions. The city of Tukwila had to do something to separate railroad and vehicular traffic.

The problems

The detour route minimally impacted commuters while cutting considerable time off the construction schedule. |

An overpass would require modifications to the street grid and would be too expensive and an eyesore. An underpass would encounter poor soil, a stream, and a water table that made the site a virtual underground lake, not to mention cramped roadway expansion, a wetland between train tracks, and a historic house in the way.

The biggest problem with either solution was South 180th would close during construction, causing detours to important retailers and businesses.

The city opted for the underpass — a grade separation — and challenged Berger/ABAM, the prime consultant, to make it work.

Heeding community needs

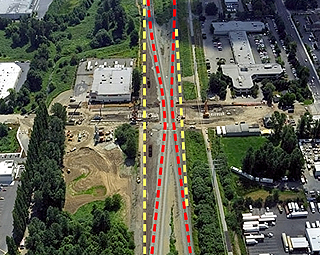

Shoofly alignments (dark dashes) allowed continuous rail traffic while construction took place on the original alignments (light dashes). |

The project team met frequently with local businesses, long before construction plans became final, so that the project could accommodate businesses’ preferences. Business owners’ biggest concerns were broken promises of project duration and how that would affect their customers. They were supportive when given advanced notice of the project schedule and an understanding of its effect on their customers.

The contractors did as promised: they stuck rigidly to timetables, and individual trip delays were minimal. The construction work was completed almost two months before the initial projections — much to the delight of the public.

The team also provided custom detour signs — with logos of popular local businesses — giving detailed directions to shoppers for specific stores, rather than generic signs. This enhancement made it easy for shoppers to get to stores as quickly as possible.

“We have had literally no complaints on the project — which, given the scope of the project is remarkable,” said Bob Giberson, the city’s senior engineer and project manager.

Tukwila Public Works Director Jim Morrow agreed. “All of the PR legwork and careful detouring paid off,” he said. “The only calls we had were after the project was over, and then they weren’t even complaints. It’s funny, but people phoned because they simply couldn’t believe everything was finished earlier than we’d predicted.”

The detour solution

South 180th Street had the only east-west railroad track crossing for four miles between Interstate 405 to the north and South 212th Street in Kent to the south. Neither of these other roads were close enough to South 180th nor had enough capacity to be suitable detours.

The only option was to detour South 180th Street’s 40,000 vehicles per day on temporary lanes just north and south of the construction site. That move would have created safety hazards, added years of construction time and displaced businesses.

However, early coordination with the city of Kent revealed the city’s South 196th Street railroad overpass project would finish in time to serve as a detour if South 180th Street’s construction was delayed. This detour allowed work to be finished earlier than if heavy traffic detours surrounded the construction site.

3 technical challenges

The South 180th Street underpass was finished nearly two months early. |

The design and construction teams on this project encountered three complex technical challenges:

1.) The water table 5 feet below the surface could not accommodate a 30-foot-deep underpass.

2.) Weak and unstable soils could not bear estimated railroad bridge loads.

3.) Rail traffic running directly through the site had to remain operational 24 hours a day, seven days a week, while the underpass and bridge construction was under way.

The solution to the underpass was to construct a boat-like structure in the ground. This structure would have a bottom and sides like a typical boat, but it would have to be heavy enough so as not to float under the groundwater buoyancy forces.

Engineers addressed the first two challenges by designing the underpass to have a CDSM (cement deep soil mixing) seal forming the bottom of the boat. Borrowing from waterfront projects, the designers had a CDSM contractor inject cement slurry and mix it into native soils. This created a waterproof, heavy, non-buoyant block of soil concrete 800 feet long by 80 feet wide and as much as 60 feet below ground, without ever having to excavate or dewater the underpass.

The South 180th Street grade separation is the first-known application of CDSM technology for a permanent roadway bottom seal in the United States. Any other viable option would have been wrong for the soil conditions or added millions of dollars to the cost of the project.

Secant pile walls

Excavating and dewatering the site to install standard underpass walls at South 180th Street would have damaged many nearby buildings. Driven piles or individual drilled shaft foundations couldn’t be used for a depth exceeding 110 feet in the weak alluvial soils. Again modifying an existing technology to come up with a solution, the design team used overlapping drilled (secant) piles that, when constructed, served as the watertight sides of the boat.

The design team showed the two 600-foot-long secant pile walls were able to spread the bridge loads enough for shafts only 60 feet deep to support them. As a result, concerns were satisfied and stakeholders saw tremendous cost savings.

Train traffic

The railroads had to remain operational throughout construction. Berger/ABAM engineers designed three “shooflies” (temporary lanes of track through the center of the project) so that diverted trains could maintain their usual speed. Once the bridges were completed, the tracks were switched back on their original alignments, which now crossed over the new underpass. Throughout the construction, the only delays were during the switch to the shooflies and finally back to the original alignments.

Successful solutions

Through the introduction of innovative technologies along with proven existing technologies and constructions, Berger/ABAM created designs that replaced other costlier and more time-consuming methods, while accommodating environmental issues. In addition, sensitivity to community concerns kept business and commuter inconvenience to a minimum.

Chris Walcott, PE, is a project manager with Berger/ABAM Engineers. He has 20 years of engineering experience, with 15 of those planning and designing complex transportation projects.

Other Stories:

- A beautiful tomorrow for structural engineering?

- 7 Engineering Wonders: Structural — How to keep it all working after the BIG ONE

- Infrastructure: out of sight, out of mind?

- Engineering a sea change at the aquarium

- ACEC says ‘yes’ to roads and ‘no’ to lawsuits

- Engineers, architects join forces on public policy

- Is our engineering rank slipping in the world?

- 7 Engineering Wonders: Electrical/Communications — Engineering a hospital to save lives

- 7 Engineering Wonders: Mechanical — EMP: an experience unlike any other

- 7 Engineering Wonders: Environmental — Brightwater planning raises awareness, not eyebrows

- 7 Engineering Wonders: Transportation/Infrastructure — Tunnels keep traffic flowing out of sight

- 7 Engineering Wonders: Geotechnical — A firm foundation for the new Narrows Bridge

- Geotechnical engineering gets a tech boost

- Finding workers may be engineering’s biggest challenge

- ACEC members pick the best of 50 years

- What a difference 50 years make

- What makes engineers tick?

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.