|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Architecture & Engineering

| |

May 6, 2009

Richard Gluckman on Olive 8, Seattle and what future holds for architects

Journal Staff Reporter

Richard Gluckman of the New York City-based international design firm Gluckman Mayner Architects designed the exterior of Seattle's Olive 8. Bellevue's Mulvanny G2 Architecture was project architect. The 39-story, $162 million building at Eighth Avenue and Olive Way was Gluckman Mayner's largest commercial project outside of New York.

The firm is probably best known for its museums, with past projects including the Dia Center for the Arts and renovation of the Whitney Museum in New York, The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, The Georgia O'Keeffe Museum and Study Center in Santa Fe, N.M., and the Mori Art Center in Tokyo.

Gluckman has been a visiting critic at Harvard University, Syracuse University and Parsons School of Design. In 2005, he won a National Design Award from the Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum.

The DJC caught up with Gluckman recently to talk.

| Gluckman speech here on Thursday |

|

Architect Richard Gluckman of Gluckman Mayner Architects will speak at the Seattle Central Library from 6:30 to 8 p.m. on Thursday. Tickets for the event, presented by Space.City, cost $10 if purchased in advance, and $15 at the door. Tickets can be purchased through Brown Paper Tickets at www.brownpapertickets.com/event/64353.

|

Q. How is it seeing the building?

A. It's really thrilling. There's three good moments when you're an architect: One is when you sort of feel that the design coalesces and you think you've got a good idea and it moves ahead. And then, when the frame goes up, that's really exciting because then you see the nature of the space you designed. And the third moment, of course, is when it's finished. And then post-partum depression sets in.

Q. Do you have post-partum depression on Olive 8?

A. Yeah, I always have it. But it's gotta be built before it's architecture. I don't do it to make drawings. I do it to see things built. It's gratifying when they're finally built.

Q. Tell me about your process.

A. We're always looking for new expressions or new ways to advance design. And by doing that, we consider context. The context can be a lot of different parameters. That includes the geography, the latitude, the historic parameters, the jurisdictional parameters, the financial parameters, the building types around it, the constructibility issues.

We take all of these things... and that gets distilled into an idea. And then the idea begins to manifest itself into drawings and models, and then they get more and more sophisticated, or more realistic. And, I have to say that we've fallen into the trap in the past of falling in love with an image, and then it's built and somehow it's different. So, there's always a certain amount of fear when you're doing something new or something different than what is tried and true.

Q. You had that fear with the Olive 8?

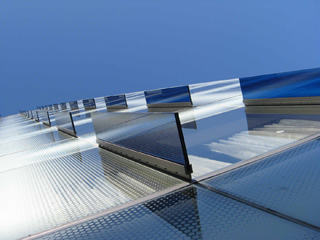

A. The technology of the curtain wall and the glazing system and the fritted glass and the way light acts on it is not always predictable. Even though we did large scale mock-ups of certain pieces of the glass, we never saw it all together. When it finally comes together and there are certain things that are unexpected or it exceeds expectations, which this has, we feel extremely gratified, extremely pleased.

Q. Tell me about the Olive 8 design.

A. We designed the building so it could be seen both frontally and tangentially. Most pedestrians will approach the building from a tangent. We knew people who would see it coming off the expressway would see it frontally.

The color and the arrangement and the depth of the fins was something we looked at carefully. And how it appears on the ground floor. Looking at the building from a distance and then how it appears as you approach it and get really close to it. You're dealing with a much more intimate scale on the sidewalk.

The building has three major elements... the base, the hotel and condos, and we wanted to distinguish between the three. The blue glass is in some ways more predominant at the top and bottom. At the hotel and condo level we used vertical blue to pull all of that together. Different types of glass were used in different ways.

Q. How do you insure street-level appeal?

A. On all of our buildings, we design considering all of these different scales. The scale of the precinct or the neighborhood, on down to the scale of the individual. As one approaches the building, you have to read it at a more intimate scale. It doesn't matter if it's a museum or a commercial project. We approach them the same. The relationship at the street is critical.

Whether the Seattle design review board had (street-level design) criteria or not, we would have designed with the pedestrian in mind. We didn't want (the street-level design) to be a separate experience from the rest of the building, we wanted it to be an integrated design expression that added some character to the street.

Q. Why did this project work well?

A. It ties into the relationship with the client. Developers in general, as most clients, are concerned with the bottom line. Varying from the pro forma of past projects is something we credit. (Developer R.C. Hedreen was) a dream client for allowing us to go in a different direction with designing this project... For a developer to realize good design brings value to a project, I think, is really critical.

Q. How does the recession affect your feelings about the Olive 8?

A. As I've gotten more experienced as an architect, I always assume everything will be worked out when it gets built. There are many, many projects that get abandoned or postponed for different reasons, and we're seeing a lot of that lately. But even before this recession, not everything we worked on got built. When we do see something built, I'm just extremely grateful that it happened. I'm glad we got it in under the wire.

Q. How was working in Seattle?

A. Compared to New York City, it's a more congenial environment to work in and an easier market to work in than New York. It just seems to be less adversarial.

Q. What will architects face in the next year?

A. The field is going to get intensely competitive in the next 10 months as we all scramble for fewer projects, but that's also going to be true on the construction side, so institutions, universities, schools, municipalities will be able to take advantage of a very competitive bidding environment six, 10, 12, 18 months from now. I think that where there is money, institutions will take advantage of that situation, and hopefully that will help fuel the recovery. I hope we can take advantage of that too.

We are all looking for work and it's going to be highly competitive. It's going to be a balance between how much are you going to be willing to lower fees and produce the highest quality work, because producing higher quality work demands more time and efforts. There is far more documentation done on a Frank Gehry building than on a commercial office building.

Q. Any advice for young architects or students?

A. I say to young architects: Go out and get design-build (experience) or do construction. Go do something peripheral to the profession that you might not be able to do otherwise once you get into the track of being an architect.

There's a huge amount of work for engineers that's coming. And we've seen that coming for five years. The need for infrastructure reconstruction in this country has been pressing for 10 years. I think there are other parts of the building profession that are really going to benefit and I encourage people to start looking in those directions as well.

I think there's going to be a redirection toward civil engineering, structural engineering in this country. And more efficient ways of putting buildings together, more design-build and hopefully a more transparent relationship between designers and engineers and builders.

Q. How will this recession change architecture?

A. I think the recovery, when it happens, is going to be strong. I think there's going to be a new set, another set of values about design. A good design doesn't demand a big budget. A good design should be judged also by the more limited resources available to it.

This interview with Richard Gluckman was conducted and edited by Shawna Gamache.

Shawna Gamache can be

reached by email or by phone

at (206) 622-8272.