|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Environment

| |

May 23, 2007

Portland's living building will be costly experiment

Journal Staff Reporter

Portland developer R. Peter Wilcox will push the envelope on green building this fall when he starts constructing one of the first living buildings in the country. But he'll also push the price, because it will cost him more than twice what an average building costs.

The Kenton Living Building is designed by Sera Architects to meet the standards of the Living Building Challenge, a new green design concept written by Jason McLennan of the Cascadia Region U.S. Green Building Council. The challenge has 16 requirements that range from being energy self-sufficient to picking a site that won't negatively affect wetlands, wildlife habitat or farmland.

Wilcox said Kenton will have four or five units of housing and a day care center. At about $2.5 million, it will cost him 135 percent more than the typical cost of such a structure. The $500,000 cost per unit is a bit steep, he said, but it will be worth it.

“I've been an architect for 25 years and this is the most complex and difficult architectural project that I've ever worked on,” Wilcox said. “We've had to look at everything really from a ground-up perspective.”

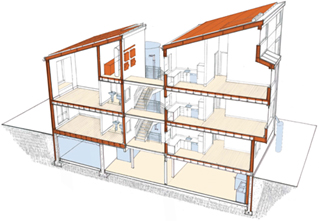

The building will catch and treat water through a variety of methods, including a basement cistern large enough to supply water for more than five months. It will have highly efficient systems, a reduced energy load and solar panels. A digital system will display energy use and generation to the public.

Wilcox's company, Renewal Associates, is working on a habitat exchange to compensate for the land the building will occupy. It is working with the Columbia Land Trust to purchase and set aside a 5,300-square-foot parcel of otherwise developable land in the lower Columbia River Estuary. The land may be used to produce certified green lumber grown using compost from the Kenton Living Building, Wilcox said.

Changing expectations

| To learn more |

|

This is one of an occasional series of DJC stories on green design concepts submitted in the recent Living Future Design Competition. For more information on living buildings see the Cascadia Region U.S. Green Building Council’s Web site at http://www.cascadiagbc.org.

|

Clark Brockman of Sera said the goal is to design in a way that changes the way people live or work in a space.

“Instead of buying your way to green, you want to design your way to efficiency through reducing demands,” he said.

Unfortunately, as evidenced by the project budget, designing a path to green is still pricey.

Lisa Petterson of Sera said when creating a self-sufficient energy system, the first half doesn't need to cost more. It can be achieved by reorganizing and rethinking systems, such as getting orientation of the building right.

The second half is where the cost comes in, Brockman said, because it requires working with new systems, and Kenton has lots of new systems. “No one thing is making it expensive but doing it all at once is making it very expensive.”

Tenants will be more involved with the building than usual, with specifications of the unique relationship written into the lease.

“It's not going to be your typical apartment. You're going to be told that you only have a certain amount of water budget,” Brockman said.

Each inhabitant can use about 18 gallons of water per day, compared to the U.S. average of about 50, Petterson said. Tenants will also have an energy budget, be prohibited from smoking on site or using yard fertilizer, and be required to use environmentally friendly cleaners and bathing products.

Zero water

Water was the most difficult area of design, the team said. To produce all the water tenants need, the team is using innovative systems as well as limitations on consumption.

Water use will be cut by using ultra-low-flow showerheads, faucets and dishwashers. Self-composting toilets will use one pint of water for each flush, compared with efficient toilets that use 1.6 gallons per flush. A special washing machine will use 4.5 gallons of water per load, compared with a high-efficiency washer that uses 12 or a top-loading washer that uses up to 40.

Water will come from two sources. About 90 percent will come from rain, which will be collected, treated and stored in a basement tank that holds 40,000 gallons, enough to keep the building water independent through Oregon's dry season of five and a half months.

The remaining 10 percent will come from reusing gray water to wash clothes and flush the composting toilet. Gray water is left over from any faucet, but not the toilet.

But reusing gray water is illegal in Oregon, so the team is appealing city codes. They expect to be successful, they say, because other Portland households have already been exempted.

Petterson said pushing city codes fulfills another aspect of the living building challenge and the green building movement. “One of the points of the Living Building Challenge is to bring jurisdictions along with what needs to change in the industry, and this is one opportunity to change.”

The project team is getting advice on challenging the system from local experts and a member of the state plumbing board.

Looking for donors

The team is finding financial support from donors and awards to help support the cost.

It recently won second place in the Living Building Design Competition's “most realizable” category and received a $139,000 grant from the Office of Sustainable Development in Portland, one of the largest amounts ever given from its green investment fund. Wilcox is donating his $250,000 development fee. But the project still doesn't pencil out.

“It doesn't pencil out and it never will,” Wilcox said. “It will pay for itself when it is completed.”

Wilcox said part of the value is setting an example for the team, the industry and the city of Portland.

“It's important to push green building and get some examples of living buildings built so people can see what they're capable of,” he said. “What we're doing here is really a research project on the building systems.”

Michael Armstrong of Portland's Office of Sustainable Development said the city hopes to see real public benefit from the project. “This project really brings together all of the elements that we like to see in a green building. That is quite unusual.”

The city will hire a separate firm to study and document the project claims.

Brockman said, “We know that our story will get told and retold back to the city in a very public way.”

Katie Zemtseff can be

reached by email or by phone

at (206) 622-8272.