|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Real Estate

| |

January 6, 2004

Eugene Horbach died 'chasing his next deal'

Journal Staff Reporter

One broker said Horbach told him a few weeks ago he wanted to get the Bellevue Technology Tower site back. The project was foreclosed on in 2002.

|

Friends and family gathered Monday for the funeral of Eugene Horbach, the Bellevue developer who built a real estate empire after arriving in America nearly penniless and unable to speak English.

His daughter, Dr. Nicolette Horbach, said his stubborn and opinionated ways could sometimes infuriate people, yet he was "generous to a fault." She compared her dad to "a rough, tough cream puff," hard on the outside but soft and sweet at the core.

Horbach died Jan. 1 at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle from complications he suffered after a fall on Dec. 23. He was 77.

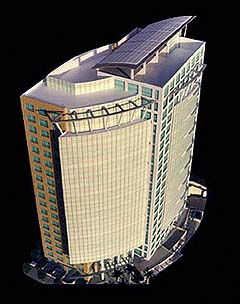

The developer had sustained some financial setbacks in recent years, but was planning a comeback despite battling health problems, according to commercial real estate broker Brian Hatcher of GVA Kidder Mathews. Hatcher and colleague Jeff Chaney worked to find tenants for Horbach's ill-fated Bellevue Technology Tower, which was foreclosed on in 2002.

Several weeks ago, Hatcher said he met with Horbach to discuss acquiring property at Northeast Fourth Street and 112th Avenue, where Hatcher said Horbach envisioned a mid-rise office building.

"Then at the end of the meeting he said, 'Let's talk about major tenants in the market because I want to try to get the Tech Tower site back.'"

"Despite his failing health he never gave up," Nicolette Horbach said. "And he died as he lived, chasing his next big deal.

"I still believe he is wheeling and dealing with God and St. Peter, trying to negotiate a better place in heaven or even building a bigger heaven for God."

An epic journey

Despite his high-profile projects, Horbach was an intensely private man. He rarely spoke with the press about his deals or his journey from war-ravaged Europe to the United States.

"It was hard for my father to trust," Nicolette Horbach said. The experience of fleeing his home as a child instilled in him a tenacious will to survive, she said.

He was Ukrainian but lived in Poland when the Nazis invaded Sept. 1, 1939. He helped his parents load some of the family's possessions into a horse-drawn cart and watched as they set their house on fire to keep it out of the Nazis' possession.

"As they fled, he witnessed carts of whole families careening off of wooden bridges..." his daughter said. "He came upon fields of Polish cavalry slaughtered by German tanks. What an impression this would make on a 12-year-old boy."

Horbach ended up in a refugee camp where he befriended U.S. soldiers. He graduated from the University of Darmstadt in Germany in 1950 and moved to the United States, where he served in the Army for two years.

He is survived by his wife, Joyce, and their three children: Nicolette of Washington, D.C., Sandra Horbach of New York City, and Eric of Bellevue, along with five grandchildren.

He built his empire slowly, starting in the 1960s. He eventually teamed up with Seattle developer Michael R. Mastro. In the 1980s, they built office buildings for Boeing in South King County and later sold them to the aerospace giant. Mastro couldn't remember exactly how many Boeing buildings they developed but estimated they sold them to the company for between $250 million and $300 million.

Mastro said Horbach was "a very smart guy," who was controversial and antagonistic "but a softy nonetheless."

Horbach's fortunes shifted with the market. During the 1990s, he was extremely active in downtown Bellevue. He planned a mixed-use project on a 9-acre superblock bounded by Northeast Eighth and 10th streets and 106th and 108th avenues northeast.

When the dot-com bubble burst and the commercial real estate market went flat, he lost the $110 million Tech Tower and sold much of the superblock, though he reportedly kept a limited interest in the project. He also placed at least two properties in Salt Lake City in bankruptcy protection.

The extent of his holdings at the time of his death was not clear. A call to his company, E & H Properties, was not returned Monday.

Thrill of the deal

Development was never really about money for Horbach, according to Hatcher. "This was Monopoly to him. He thrived on doing deals."

Some real estate pros described Horbach as mercurial, and that's a fair characterization, according to Hatcher: "There were good days and bad." But he said much of the criticism of him was unfair. "For the most part, all the people who said bad things about Gene didn't know Gene."

What was important to Horbach, Hatcher said, was family. The broker remembers the day Horbach called to tell him about taking his grandson to the bottom of the deep Tech Tower hole. "I could just feel his pride and (see his) smiling face when he was talking to me about that."

Nicolette Horbach said she thinks her dad believed his developments would be his legacy, but she disagrees, saying he will be remembered for "the memories he created, the lives he touched..."

He had interests outside of work and family. Horbach collected Asian art, was a supporter of the Seattle Symphony and sponsored an endowed fellowship for the University of Washington's Department of Neurosurgery. He was a member of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

Memorials can be made in Horbach's name to the Northwest Kidney Centers Foundation, P.O. Box 3035, Seattle 98114.