|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Commercial Marketplace 1999

|

|

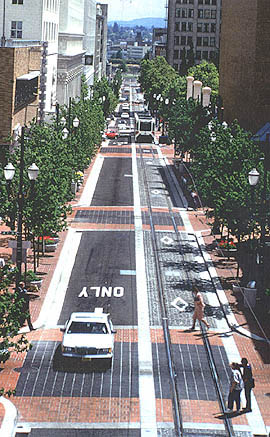

A look at Portland's experience with rail, real estate

By BRAD BROBERG Some people in Portland missed the train. Now, they're chasing the caboose. When Portland built the first leg of its light-rail system in1986, the city's largest shopping mall opposed placing a station at its entrance. And a nearby suburb fought laying tracks through its downtown. Lloyd Center and city of Gresham merchants feared the trains would disrupt traffic and ruin business. So Tri-Met, the three-county agency that runs Portland's transportation system, chose alternate sites nearby. Relieved at the time, Lloyd Center and Gresham have come to regret their victories.

"For them, it's a lost opportunity," said Arrington. Since that time, Lloyd Center has rewritten its master plan and reconfigured its "front door" to face the station. And Gresham is focusing redevelopment around the rail corridor instead of in the established downtown core. Is there a lesson for Seattle-area communities and developers about the value of rail? "The lesson is, you've got to learn how to think longer term about these things," Arrington said. Seattle is just now setting foot on a path Portland began traveling in the1980s. Sound Transit, the local equivalent of Tri-Met, is designing a 23-mile light-rail line stretching from Northgate to Sea-Tac and a 1.7-mile spur in Tacoma. The light-rail line, known as Link, will mesh with two other components the Sounder commuter rail line between Everett and Lakewood, and Regional Express bus service throughout the region. Approved by voters in 1996, the three-county, $3.9-billion system is known collectively as Sound Move. Although its primary mission is to relieve the congestion that chokes the region's freeways, the system has the potential to stimulate economic growth and steer future development to areas around major stations. The key word is potential. It may take many years just as it has in Portland before the iron horses become economic work horses. "The hardest part is getting started and getting some initial projects that other developers can replicate," said Arrington. "Nothing sells like success." The popularity of MAX's first phase, which stretches15 miles east to Gresham, spurred a second phase. Completed last year, it runs 18 miles west to Hillsboro. Although MAX remains heavily subsidized, it runs at capacity during rush hour and carries 50,000 passengers a day 10,000 more than projected, said Arrington. In a sense, the Gresham leg paid some dues for the Hillsboro line, which received a much more enthusiastic welcome from neighborhoods and developers. They didn't have to imagine what light rail would look like. They could ride it. Demographics also played a role in how the two lines evolved. Tri-Met placed the line to Gresham "where the people were," but put the second line to Hillsboro "where the people will be," said Arrington. "We use light rail as a tool to direct growth." According to Tri-Met, $500 billion worth of development has occurred along the Hillsboro corridor since residents voted in 1990 to extend the line west. And not just any development, but numerous mixed-use villages that cluster high-density communities around stations to create pools of riders while checking urban sprawl. "We don't .... say development happened in Portland because of light rail," said Arrington. "We believe a lot of development happened diffrently because of light rail." Orenco Station is a prime example. When Tri-Met selected the 190-acre site east of Hillsboro to build a station, it was empty farmland destined to become a commercial/industrial park.

The situation could have turned into a confrontation, but it didn't. "We found them (Tri-Met and Hillsboro) to be very reasonable," said Peter Bechen, president of PacTrust. Today, a mixed-use village named for the station is rising there with 2,000 units of housing, a neighborhood shopping center and office space. It recently won an award from the National Association of Home Builders as best planned community of the year. Orenco Station offers two mo als for proponents of transit oriented development. First, transit agencies and local jurisdictions must cooperate, since the former controls the location of stations and tracks and the latter controls the land use that surrounds them. Second, public authorities must give developers the support they need to make a project pencil out. "Just because you have a light rail station there doesn't mean you can build anything and have it be successful," said Bechen. "There has to be a cooperative atmosphere between the public and private sectors so the planners aren't just ramming something down your throat that won't be acceptable to the market. "It's important that there be some incentives to help make these projects feasible." Tax breaks, grants and infrastructure construction are some of the carrots local governments can wave to attract developers. For example, at Orenco Station, PacTrust successfully argued for more parking and slightly larger lots than planners originally envisioned, said Bechen. But development on the scale of Orenco Station requires more than public-private goodwill. It demands acres and acres of empty land, which wasn't available when MAX laid tracks along the more urbanized route to Gresham and won't be available along Sound Transit's Northgate to SeaTac route or downtown Tacoma spur. (Sound Transit ultimately plans to seek voter approval to extend the line farther south and north) That doesn't mean the cause is lost. Just that instead of bursting into existence like mushrooms on steroids, urban projects may be more modest and take awhile to sprout. "Redevelopment is much harder than new development," said Gussie McRobert, former mayor of Gresham, who had supported plans for MAX to run downtown. One reason: the tracks run through established neighborhoods that often oppose them. Mike Bernick is the former president of the BART board in San Francisco and author of a book entitled "Transit Villages in the 21st Century." He says community support is every bit as vital as cooperation between transit agencies, local governments and private developers. "Most neighborhoods don't want any additional development," said Bernick. "You have to show them how the development will bring about services and value ... not just how the region will benefit." Bernick believes rail has tremendous potential to stimulate development, but not without a conscious effort. "When BART first started in the 1960s, the idea was development would naturally occur at stations through market forces. That never occurred." Instead, BART and Bay Area cities are just now tackling projects tied to rail. The same thing is happening in Gresham, where the city invested $2 million constructing the infrastructure necessary so a private developer can create a 700-unit "European-style" village along the rail line, said Greg Parker, city spokesman.

Built by Paul Allen as the new home of the Portland Trailblazers basketball team, the Rose Garden's location along the MAX tracks in the Lloyd District complete with its own station is no coincidence. "Without light rail, it might have occurred in the suburbs," said Arrington. "Without light rail, it would have needed more parking." According to Tri-Met, 20 percent of the team's fans arrive by train. As the Sound Transit Board prepares to vote Feb. 25 on a final light-rail alignment including whether to build a tunnel below the Rainier Valley the agency's planners have made numerous trips to Portland to learn from that city's experiences. Bill Houppermans, manager of civil engineering for Sound Transit's light-rail development, said that like MAX in its early stages, the Link rail system has yet to light a fire under the private sector either for joint development of stations or independent development of surrounding property. The first trains won't hit the track until 2001 in Tacoma, followed by service between downtown Seattle and SeaTac in 2004 and downtown Seattle and Northgate in 2006. Although Sound Transit officially supports joint development and has received feelers from developers eyeing the Northgate and SeaTac stations, "everything's kind of potential right now," said Houppermans. Paul Sleeth, a broker with Collier's International, agreed. "The horizon is just too far out," he said.

djc home | top | special issues index

|