|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Protecting the Environment '99

|

|

It's time to try zero-impact

By THOMAS W. HOLZ Evidence is incontrovertible that development destroys fish habitat. For over three decades the literature has documented the devastation of streams in watersheds when they are urbanized. The latest in a long string of papers on the subject is by Chris May and Richard Horner ("Salmon In the City Conference," 1998). They corroborate the near total destruction of stream habitat when a watershed reaches impervious surface percentages between 10 and 20 percent. The steepest decline in habitat quality begins when the first few percent of forest are converted to pavement.

To date, we have depended on stormwater design manuals required by regulation to protect habitat. Though the storage volume to contain runoff from new development has been steadily rising for over 20 years, evidence shows that engineering approaches have not been effective at preserving receiving waters. In a paper presented by Beyerlein and Brascher (1998) at the "Salmon In the City" conference, it was shown that such methods have little chance of simulating forest cover, regardless of storage provided. It is clear that if we are to save salmon habitat our options are few: stop development or find a way to develop that doesn't impact habitat.

ESA adds pressure to change our waysAlthough we have known for some time of the devastating impacts of development on streams, this knowledge alone has not provided sufficient motivation to change, in fundamental ways, the way we develop land. Urbanization is occurring in the Puget Sound basin at record breaking levels, even though it is well known that each acre developed is harmful to salmon habitat. Yet our attempts to mitigate the effects of development are still pinned on discredited, "end-of-pipe," engineering solutions. But now it seems to be dawning, albeit slowly, that what we do to the land in the process of development can't be mitigated. The federal Endangered Species Act may provide motivation for change. It provides that threatened or endangered species may not be "taken." The definition of "take" includes destruction of habitat. If a development project will "take" such species, the law provides no latitude to claim "economic hardship" or "vested rights" just because permits have already been granted. That project can be stopped by the courts immediately and permanently.

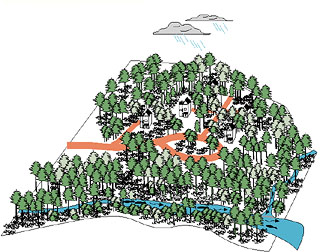

What happens to streams when we develop land?In the Northwest, vegetation in a pristine watershed will evaporate/transpire about half of the annual precipitation. The other half, for the most part, is stored in the thick duff and soils on the forest floor to be infiltrated to deep groundwater and released over weeks, months and years to surface water. After development, vegetation gets cleared and the duff and soils on the forest floor are removed. Rainfall that previously evapo-transpired now becomes runoff and thus nearly all of the annual precipitation runs sheet flow off the land and is diverted to surface water. And it is released in a matter of hours instead of months. Groundwater recharge is significantly reduced. Removal of the forest effectively doubles annual runoff volume and pavement causes a dramatic increase in peak flows. Consequently, stream channels are dredged as if a fire hose had been directed at them. Salmon spawning and refuge habitat disappear, pools disappear, and the channel gets wider and deeper. In the summer, flows that were fed by groundwater are reduced and are spread thin in the newly dredged and widened channel. Water temperature soars. Quality of water declines precipitously. Few will argue that development, as it has been practiced to date, does not "take" salmon.

Characteristics of a healthy watershedSpeakers at the Salmon in the City Conference defined the minimum characteristics of a watershed which must be maintained if habitat is to be preserved. They are: At least 60 percent of the forest must be preserved to provide fish and other aquatic life with year round, cool, well modulated stream flows, shelter, and food.

Broad buffers of undisturbed native riparian vegetation must be maintained. Road crossings of the riparian zone must be minimized.

What does zero-impact development look like?Current site design largely ignores existing land contours and vegetation. A grid system of streets and building sites, usually intended for one or two story structures, is imposed regardless of the shape of the ground. Land is cleared and grubbed, graded, benched and terraced with the goal of maximizing buildable space. Generally, one owner will create lots and prepare the site. Lots are then sold and subsequent owners will build on the lots. Usually little or no planning of structures or landscaping is done at the site plan stage. By contrast, zero-impact development's goal is to maintain characteristics of a healthy watershed and to turn a forested site to human uses with no measurable impact on receiving waters. Such a design requires planning of site and structures to act in unison to meet this goal. SCA Engineering has been developing procedures and designs for such a project. For example, design would begin with an inventory of significant trees, careful measurement of existing contours, and location of natural drainage features. Next, roads would be designed to follow existing contours to the maximum extent possible. Structures would be located last. Roads would be the minimum width to meet "functional" requirements (not necessarily the current "regulatory" requirements). Imperviousness of roads would be further reduced through the use of innovative surfaces. Structures would be tall rather than rambling (to reduce footprint) and might have runoff attenuation as part of the design (such as garden rooftops). Rain gutters and downspouts would be eliminated as they concentrate flow a violation of "zero impact" principles. Structures would be widely spaced to allow natural vegetation to buffer them and to "disconnect" their impacts from downstream habitat or property. Structures might span over roadways to minimize impervious surfaces. Covered bridges would not be just a quaint artifact to attract tourists; they would support garden roofs to mitigate runoff. Parking that couldn't be placed under structures would be covered with garden roofs to the maximum extent possible.

No stormwater collection system would be constructed. The forest would remain largely intact and would be the "stormwater management system." Zero impact projects would provide a test of design skill and many innovative foundation, paving, and roofing techniques and materials. The cost of zero impact development has not been rigorously estimated but it is believed that cost savings (narrow roads, no storm drainage collection) should offset much of the higher costs associated with innovative construction practices and materials. Furthermore, if the cost of stream restoration is added to the equation, zero impact comes off far less expensive.

BenefitsThis first such project to be constructed will demonstrate that land can be turned to human purposes without devastating impacts on receiving waters. The benefits of having made such a demonstration in the face of extinction of species dependent on such habitat can't be overstated. If fish habitat is to be preserved in watersheds with fish bearing streams, it is SCA Engineering's opinion that zero impact design offers the only alternative to halting of development.

Thomas W. Holz is hydrologic services director for SCA Engineering in Olympia.

djc home | top | special issues index

|