Landscape Northwest Issue Home

April 20, 2000

A catalyst for change: the new urban corporate campus

Fitting new environments for research and teamwork into the city

By ROBERT SHROSBREE

EDAW

Seattle and the Puget Sound region currently lead in the development of both urban and suburban corporate campuses, and local developments are setting the standard for other communities throughout the nation.

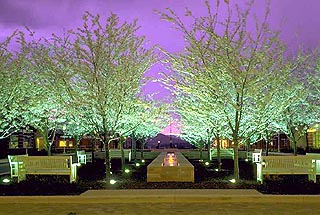

Genencor Technology, Palo Alto, Calif.

Genencor Technology, Palo Alto, Calif.

Photo by Dixie Carillo

|

Microsoft�s Redmond campus has dramatically increased density while retaining a strong vision with a clear system of open space and amenities. The Adobe campus in Fremont has provided both a gateway to the neighborhood and a catalyst as a good corporate neighbor in a very lively district. Zymogenetics, in their adaptive re-use of a former power plant, has been a pioneer in the redevelopment of the South Lake Union area. The Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center developed a creative solution for a massive in-fill in various phases on a very difficult site. Immunex will soon build a new campus at the north end of Elliot Bay that integrates waterfront, park, and open space on a former brownfield site. All of these developments serve immediate identity and long term campus planning objectives.

The common thread in these projects is that they all are high tech and biotech companies. These industries are not only important components of the economy but also provide benchmarks in corporate campus planning and design trends. Design clients from around the world come to tour these facilities and learn about what�s new and what works for them. Both nationally and internationally, corporate campuses are more innovative, resourceful, and environmentally responsible than ever before.

The corporate campus has come a long way in the last 30 years, and it has come into the city.

There is a dramatic shift here from the image of the suburban corporate campus that has dominated the market for the last 30 years. Let�s revisit the standard setting: a verdant, low density development that might mimic a traditional university campus, on inexpensive land, in a greenfield setting, with plenty of room for surface parking, expansion opportunities, easy access to transportation corridors, and suburban housing.

This is no longer ideal. In fact, the bucolic part of this image immediately erodes when a formula of three to four cars per 1,000 square feet of building emerges in a figure/ground relationship. The parking part of the equation wins in two-to-three and a one-to-three ratio. Therefore, locations that are close to urban activity, support systems, and urban redevelopment areas are now seen as a much smarter alternative. They reflect a sympathetic political structure, a progressive planning environment, developed infrastructure, cultural amenities and access to a work force that is highly skilled, more urbane and demanding.

The high tech and biotech industries are characterized by a number of economic and industrial factors that don�t necessarily translate to a clear program or set of principles for planning, development or design. However, there are a few characteristics of these businesses that we have begun to draw upon in setting a direction. They are:

|

- Extremely fast paced, competitive, and exponential in their growth. Accommodating this growth with new facilities, expansion capacity, and strategic phasing is imperative to success.

- A clean industry. High tech uses typically have the advantage of providing a positive fit within the urban environment. They are conducive to a mixed-use scenario in a district of housing, retail, office, and other uses that are of a compatible scale.

- A work force that is more independent, younger, mobile, active, well educated, and demanding. Location, work life, and access to amenities are highly valued in employee retention. Employers understand that retaining their work force in a highly competitive and demanding industry requires a deeper approach to their location and environment.

- Driven by technology with a 10 to 20 percent margin of revenue spent on research and development. Manufacturing and product distribution are not driving factors in their location or site planning.

- Independent and savvy clients who are an integral part of the planning, design, and development team. They are becoming more instrumental in defining their cultural dynamics, vision, and program while maintaining an aggressive �bottom line� and knowledge of value-added.

With these clients, what are some of the guidelines that make a campus successful in the urban design, site planning, and landscape architectural realm? Below is a framework of factors that can be applied to the new corporate, high tech, or biotech environments.

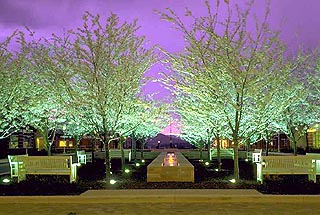

First National Center, Omaha, Neb.

First National Center, Omaha, Neb.

Photo by Dixie Carillo

|

- Proximity to a range of housing choices and services. Housing might include loft space as well as single family homes, hotels and residential stay facilities. Retail and financial services and professional services from haircutting to medical care and schools should be easily accessible.

- Amenities. Child care is important, as well as indoor and outdoor recreational facilities including health clubs, common buildings with food and beverage, and meeting rooms.

- A sense of place: This hard-to-define quality has to do with access to open space, expression of cultural and regional qualities, and feeling a part of a larger context with �finer grain� gardens, courtyards, and plazas for interaction and contemplation. There are memorable �in between� spaces-not just destinations.

- Critical mass: Proximity to reliable clean infrastructure, vendors, suppliers, and other industry related companies is important to the vitality and synergy of an urban campus.

- Transportation: Options might range from public transit to bicycles, boats, and kayaks. Shared transportation is also an incentive point for employers to offer in their compensation package.

- Vision: It�s important to establish a clear set of planning principles and guidelines that reflect a corporate mission, community spirit, an aesthetic vocabulary and environmental value provides a foundation for subsequent planning and implementation.

- Community and municipal support: Strategic guidance and input from agency and regulatory managers, neighborhood, and special interest groups is absolutely essential to ensuring acceptance, gaining entitlements, maintaining the momentum of a project, and securing a long-term acceptance.

Thirty eight years ago, Kevin Lynch defined site planning as "the art of arranging structures on the land and shaping the spaces between; an art linked to architecture, engineering, landscape architecture and city planning." As a classic reference, the premise of Lynch�s definition in his book, "Site Planning," is both an aesthetic and pragmatic one that has social, environmental, and economic implications.

Today, we are applying these lessons while practicing the refined "crafting" of a site. Defining these new corporate campus environments presents the opportunity to create true catalysts for further innovation in planning and design. As design consultants, we are developing more intense, dynamic, animated solutions while drawing from the rich context of the urban environment. The result is a better future for our clients and our cities.

Robert Shrosbree is a principal and director of landscape architecture at EDAW in Seattle.

Landscape Northwest home | Special Issues Index

|