|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Architecture & Engineering

| |

February 6, 2013

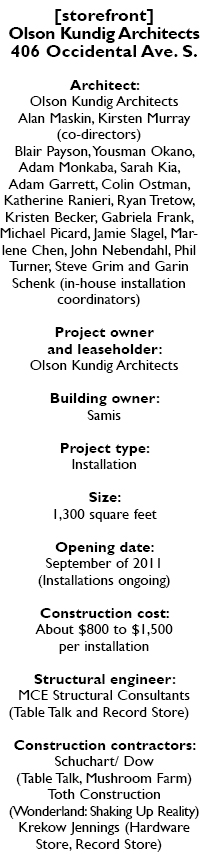

Project of the Month: OKA's [storefront]: An experiment becomes essential

Special to the Journal

Between 11:30 and 1:30 on weekdays, you can walk into [storefront] in Pioneer Square, browse the tall shelves and walk out with an armload of books. But there's nothing for sale. The books are free.

During these extended lunch hours, there might be no one there except a staff member from Olson Kundig Architects, which leases the space.

But on weekends and evenings since it opened 16 months ago, [storefront] is sometimes packed and visitors spill onto the street as they strain to hear a speaker or see a multi-media presentation.

This “store” with nothing for sale is an installation called “The Free Book Incident” at [storefront].

It might not bring in the average passer-by, but in the age of social media, [storefront] events are known to a global community. People who drop by or pack in with the crowds might be from anywhere in Seattle — or Kansas City or Amsterdam.

Hours for special events are posted on the [storefront] Facebook page. Coming up in March is “I Want All of This, All of This I Want,” an installation that involves a mechanical arm writing on the floor.

What's even more remarkable, given that [storefront] is leased by one of Seattle's most celebrated design firms, is that there is nothing about the space that has been “designed” to last more than a month or so, an exercise in restraint that is particularly challenging.

“We are designers, so we tend to throw design at things,” said Alan Maskin who, with fellow Olson Kundig partner Kirsten Murray, is in charge of programming the space.

But it's also freedom, said Murray. It's collaborative but much quicker than conventional construction, and some of what's created at [storefront] travels, like “One Million Bones,” an installation planned for April. Pieces of that will be shown at the National Mall in a campaign to raise awareness about genocides and atrocities going on around the world.

As traditionally defined, architecture doesn't play much of a role in [storefront]. Art, new technologies, community gatherings, presentations and cultural experiments all have their part, just like the free book “store” there now.

Since [storefront] opened, there have been wall-sized artworks and an exhibit of a portable farm (“Mushroom Farm”) designed for growing mushrooms. There have been readings for small groups (“The Poet is In”) — and a festival for playing and sharing from collections of vinyl records which attracted more than 400 people (“Record Store”). Performance art created there has been shown at different sites.

A lab for ideas

There's life in Pioneer Square these days. Businesses are moving into Occidental Mall, a block from [storefront], which is on Occidental Avenue between the mall and the rapidly redeveloping Stadium District.

But times have been tough. The idea for [storefront] got started when Jim Olson, founding partner of Olson Kundig, was walking through Pioneer Square, where he has lived and worked for more than 30 years.

Olson has seen more than one slump in Seattle's boom-bust economy, but waves of recession in 2009 were especially hard on retail. Elliott Bay Book Co. packed up and left, and empty storefronts spread like the flu. At a firm meeting, Olson brought up the idea of leasing one of those empty spaces and the idea of [storefront] took off.

In Seattle and other U.S. cities, there are examples of artists and cultural entrepreneurs going into neighborhoods where you can hear gunshots at night and making things happen. Maskin says what's different about [storefront] is blending this kind of neighborhood activism with the everyday life of the firm.

“It shows that an architectural team can be part of cultural production,” said Murray.

It was a stretch to lease the space in early 2011 because Olson Kundig, like other architecture firms, was cutting costs and employees. But [storefront] quickly became a laboratory for ideas and a small center of life in a neighborhood gasping for air.

First, there was a studio for design students from Washington State University, led by WSU with Olson Kundig staff as guest critics. Then [storefront] opened with the first public event, “Record Store,” in the fall of 2011.

Cultural exchange

In the end, it is a place for design experimentation and cultural exchange. Since [storefront] is in the same building as Olson Kundig Architects, it's convenient for its employees to program and staff the space.

Ideas for using [storefront] are part of the life of the firm, with presentations on future uses built into weekly meetings, and staff members adding ideas.

Virtually all interns at Olson Kundig have heard of [storefront], said Maskin. Since [storefront] opened, Olson Kundig has grown to 96 employees, the largest ever.

When the end of another six-month lease came around in December, the expectation was that [storefront] had served its purpose and the space should be put on the market, but Murray said that didn't happen.

[storefront] has become an essential part of the office culture, she said. “Things come up and we can respond. We're able to connect the dots.”

The direct results might not be clear, but “we're seeing the ripple effect,” she said.

Jury comments:

“Storefront exemplifies the versatility of a simple box as a conduit for topical discussions beyond the site. It celebrates architects as social commentators and provides a platform for invention beyond the buildings they design.

“It’s humane and accessible and totally unexpected.”

The Project of the Month is sponsored by the Daily Journal of Commerce and the Seattle chapter of the American Institute of Architects. The Project of the Month was selected with the assistance of architect Jane Hendricks, artist Mary Ann Peters, and developer Chris Rogers. For information about submitting projects, contact Joan Hermann at AIA Seattle at joanh@aiaseattle.org.

Clair Enlow can be reached by e-mail at clair@clairenlow.com.

Previous columns:

- Project of the Month: Exceptional design calms the chaos of a student fitness center, 12-05-2012

- Project of the Month: Greenbridge in White Center has a kid-friendly heart, 11-07-2012

- Project of the Month: Suburban school with a Zen garden at its heart, 10-03-2012

- Project of the Month: Modern building set inside a treasured shell, 09-12-2012

- Project of the Month: Duplex designers are also swinging the hammers, 08-15-2012

- Project of the Month: NSCC job center changing lives — inside and out, 07-25-2012

- Project of the Month: An edgy new welcome to Everett Community College, 06-20-2012

- Project of the Month -- Machias school: Bold design for a bucolic setting, 05-09-2012