|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Construction

| |

July 20, 2000

A revolution in home building?

By STEPHANIE BASALYGA

Portland DJC

Pull up a chair and let Jim Roman tell you the story about the Little Red Hen. He can sum up the children's fable in one sentence.

"No one wants to help you bake the bread, but everyone wants to eat it."

|

Roman understands the fictional hen's dilemma. For more than a decade the Myrtle Point, Ore., resident has tried to drum up support for an interlocking panel system he thinks will revolutionize the home building industry. Over the years many people expressed interest in his idea, but no one was willing to provide the seed money Roman needed to test it.

But just as they did for the Little Red Hen, hard work and tenacity may be about to pay off for Roman. He recently received a Small Business Innovative Research grant worth almost $70,000 from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The six-month grant will pay for stress tests to help Roman create a working design for his panel system.

Roman's Interlocking Construction System -- or ICS -- consists of 2-foot standard panels that fit together almost like puzzle pieces to form floor and walls. Special headers attach along the panel lengths for windows. The panels are then attached to corner pieces and bolted together to lock into a cube.

The result is a custom-sized house that can be assembled by two people without the need for cranes or other heavy machinery and erected in less time than it takes to build a traditional house.

Roman roughly estimates the cost for debut ICS homes would be comparable to the current cost for a manufactured home -- between $60 and $65 per square foot.

The combined factors of the system could create limitless possibilities. Habitat for Humanity could build more homes at a faster rate. Areas hit by natural disasters like earthquakes and tornadoes could rebuild in a matter of days.

Roman created the interlocking system as a response to a general lack of craftsmanship and quality he saw while working as a carpenter on the East Coast.

"I was at the end of my rope," he said. "I hated going into older homes, taking out the good stuff and putting in the cheap stuff. They were tearing out this old quality wood and replacing it with junk."

Frustrated and disheartened, Jim decided to leave carpentry. He and his wife, Faye, sold almost all of their possessions. Armed with only the bare necessities and two 10-speed bicycles, the couple embarked on a cross-country trip.

It was while they were riding along a road in Oregon that Jim had a flash of insight -- a home building system based on interlocking panels. In that brief moment, his future was written in mental indelible ink.

"We didn't have a home," he said. "We didn't have much of anything. But instead of running away, I just decided I was going to build things the way I wanted."

The couple decided to stay in Oregon, settling in Brookings and eventually moving to Myrtle Point. In between having four children, Faye created a line of pinecone jewelry. Roman created wooden displays for the jewelry. The couple named their new endeavor Oregonized Business.

Faye eventually branched out, incorporating crystals into a new line of jewelry she dubbed Crystalinas. Roman continued to create display boxes and pick up remodeling and trim work. In his spare time, he worked on his interlocking system.

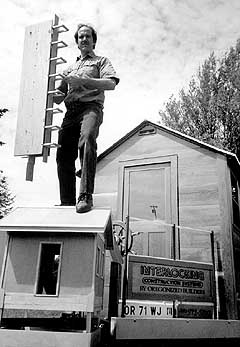

He turned a pile of spare redwood lumber into his first system model -- a dollhouse-sized structure strong enough to bear his weight when he stood on the roof.

After building three more models, he finally hit upon a design he liked. The resulting structure -- one half the size of a regular house -- now serves as a floating houseboat, outfitted with foam blocks, an outboard motor and a captain's wheel.

But even with a working design, Roman still needed to find money to finance tests of a full-size structure.

"I've been doing this on a shoestring budget," he said.

Then he learned about the Small Business Innovative Research grant program offered through the USDA. The program provides research funds for small businesses with projects related to agriculture and rural development.

"As grant programs go, it's very unique," said Dr. William Goldner, SBIR's national program director. "In some ways it's venture capital, but in other ways it's an opportunity for small businesses to compete in an arena where traditionally big businesses have had an advantage. In essence, they have nothing to lose but their time."

With more time on his hands than money, Roman enlisted the help of his sister, Judy Andrien, who has a degree in marketing. The two sat down and wrote a grant request, but the request was turned down two years in a row.

"After strike two, I just couldn't get my hopes up," Roman said. He and Judy sat down and rewrote the grant one more time.

True to the old cliché, the third submission was the charm.

Competition for program grants runs high, said Dr. William Goldner, SBIR's national program director. This year, almost 500 applications were submitted. Roman's idea was one of 90 selected to receive funding.

"We're looking for investigators to come through and provide their ideas," Goldner said. "Unlike some agencies that publish a list of ideas they want people to fill, USDA opens the door. We're looking for research that's gong to lead to a product, process or service that's going to be important to agriculture or have a positive impact on rural community development."

Although Goldner is prohibited from revealing the actual ranking of the projects awarded grants this year, he said Roman's interlocking system "was very highly rated."

A chunk of Roman's grant money is paying for stress and torque tests on several sheer wall panels built with the interlocking system. The tests are being conducted at Oregon State University's Department of Forest Products under the supervision of Dr. Rakesh Gupta.

"The SBIR funding will permit us to build a one-room test model and to test and evaluate each wall-floor and roof diaphragms for strength and load capacities," Roman said.

Under the grant requirements, Roman must provide testing updates and submit a final report of results to the SBIR program.

If the current research is successful, Roman will then be eligible to apply for a second level -- or Phase II -- SBIR grant. The second level grants, available only to projects that have already received first phase funding, offer up to $275,000 of funding for a 24-month period.

The Phase I grants are highly competitive -- this year almost 500 applications were submitted for 90 award spots. Phase II awards are easier to come by, with between 50 and 60 percent of applicants awarded grants, Goldner said.

Roman already has plans for the Phase II funds he hopes to receive eventually.

"I'd use it to build a whole test home and to expand my facility," he said.

For now the "facility" consists of a machine Roman designed and made in his home workshop. The machine, outfitted with a special jig and a vacuum system to minimize dust, will someday form the basis for mass-market, assembly line production of the Interlocking Construction System.

"I really think our country needs something like this -- a shelter that actually shelters," Roman said. "My overall dream is to create a self-sufficient interlocking home."

With an eye toward that goal, he's started mentally sketching an envelope system of exterior and inner shells with connected wall, ceiling and floor cavities to create continuous airflow. The spaces would also accommodate preinstalled electrical and plumbing components that would eventually hook into an access panel.

A more pressing challenge, however, is how the Interlocking Construction System will make the giant step from one-man operation to full-scale business venture. Eventually, Roman will reach the end of the SBIR grant trail. Then he will have to strike out on his own, a true entrepreneur in every sense of the word.

Roman prefers to use a different word to describe his efforts to change the face of home building.

"We're survivors," he said. "You're going to survive one way or another. You might as well make the best of what you have."

Stephanie Basalyga covers architecture, engineering and construction for the Portland Daily Journal of Commerce. She can be reached at (503) 221-3360, or by e-mail at stephanieb@djc-or.com.

Previous columns:

- How to keep 'kool' when it's hot, 07-13-2000

- AGC members are 'best supporting actors' for new Tacoma arts center, 07-06-2000

- Heating a home on two bits a day, 06-29-2000

- WSU offers design-build management degree, 06-22-2000

- Siding panels use gravity to keep the rain out, 06-15-2000

- Company has the poop for keeping birds away, 06-08-2000

- Creating a little desert indoors, 06-01-2000

- Living in a cardboard house, 02-24-2000