|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Architecture & Engineering

| |

|

February 29, 2024

An uncertain forecast for middle housing

CAST architecture

Hutchins

|

Many Washingtonians struggle with housing, and it isn’t just homelessness and high rent. Finding a home you can afford, not being able to buy or relocate for opportunity, struggling to stay in your neighborhood as your family situation changes or as the economic pressure of gentrification and displacement push up prices — these are commonplace features of a city that can’t keep up with housing demand.

Housing costs have doubled across the state in the last decade, making the lack of attainable housing for low and middle-income people a pervasive problem.

Among the most promising strategies to open more doors for new homes is ‘middle housing’, a catch-all for the mix of housing types between the scale of detached single-family houses and large apartment buildings. They are typically townhouses, small multiplexes, accessory dwelling units, and cottage clusters. They fit on most residentially zoned lots, but split the land cost across more units, making each unit relatively less expensive. And although they tend to be similar in bulk to larger houses, many places have thrown up walls to keep out this kind of new building.

CITIES MAKE SPACE FOR MIDDLE HOUSING

The movement to create space in detached single-family house neighborhoods for denser housing types is catching fire nationwide. Portland, Sacramento , Charlotte , and Austin are planning for two to six units per parcel. Minneapolis rezoned to allow three units in 2019 but subsequently has had to put the new rules on ice until concerns by several environmental groups are studied.

Spokane is leading the way in Washington state with its Building Opportunity for Housing program.

In 2022, Spokane declared that it would allow four or six units per parcel in residential zoning and it has led to a wave of alternative housing types such as the upcoming Spokane Six stacked flats. The Spokane Six features six two-bedroom/two-bath family-sized units, two of which will be made affordable using the Multifamily Tax Exemption. The project will replace a detached single-family house and recalls the small multiplexes that once were the building blocks of cities before single-family houses became the zoning paradigm.

MOVEMENT AT THE STATE LEVEL

It isn’t just cities addressing the housing crisis. States are taking up the mantle. California’s SB9 and ADU reform are generating about 20% of all of the new units there. In 2019, Oregon’s HB 2001 allowed 2-4 units in urban areas. Last year, Washington joined them with HB 1110 , which directs cities and towns to provide zoning for four to six units per parcel or abide by an alternate model ordinance.

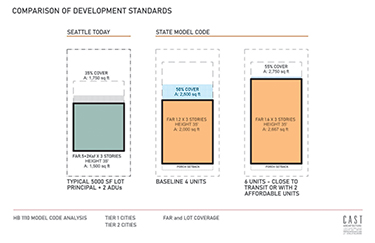

The middle housing model ordinance starts with a target of 1,400-square-foot new units, and reverse engineers the Floor Area Ratio (FAR) and lot coverage. It doesn’t discriminate between the different housing typologies, and is thus well-positioned to produce townhouses as well as small multiplexes. Prescriptive aesthetic design standards, such as building articulation, are not mandated, but will be the purview of local planners.

This session, legislators are looking at the Housing Accountability Act, HB 2113 , which would create a state-level review of local comprehensive plans to make sure their housing policies match targets, a Transit Oriented Development bill, HB 2160 , and HB1245 which would allow lot splitting — a key strategy for leveraging urban lots.

KNOCKING DOWN BARRIERS AND BUILDING WALLS

Barriers are falling for Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs). Since Seattle passed the landmark 2019 reform, the appetite for ADUs as starter houses, townhomes and multi-generational housing has been growing. The zoning change effectively created a back door for infill development.

Last year, nearly a thousand ADUs were completed across all zones, or about 7% of the total number of new units. Three-unit townhouse projects, where two homes are nominally ADUs, are springing up for sale as condominiums. Under HB 1337, jurisdictions will have to plan for two ADUs, both of which could be detached, creating de facto cottage clusters of starter homes.

While these are positive moves, middle housing still faces an uphill battle. In Seattle, the pipeline for new low-rise townhouses has essentially dried up, with only 260 new units filing applications in 2023. Many small developers have pivoted from low-rise zoning to Neighborhood Residential/ADUs to bypass the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) fee or left the market.

In those terms, the upzone component of MHA hasn’t worked — and the success of ADUs is masking the shortfall. MHA’s proposition to trade additional development capacity for affordable housing funding doesn’t have enough incentive to offset the cost for builders who have the choice to work elsewhere. It effectively doubles the soft cost paid out by the developer before groundbreaking. MHA has a 5-year track record, and it is time to re-calibrate the program’s effectiveness based on the pattern of development it is producing.

GROWING PAINS IN IMPLEMENTATION

The Seattle Comprehensive Plan , a long-range framework that guides big-picture decisions about housing, transportation, and capital investments, has been in the works for several years, but the draft has been delayed since last April. Granted, integrating new requirements for Middle Housing (HB1110), Accessory Dwellings (HB1337), Climate Action (HB 1181) and Transit Oriented Development has slowed the process, but without clarity about what will happen to land use around Urban Villages and in Neighborhood Residential (NR) zones, some developers are waiting on the sidelines until the outline of an updated growth strategy is unveiled. The possibility of MHA expanding into NR zones could be a wet blanket for infill developers looking to leverage ADUs or middle housing under HB 1110.

We are at a point when middle housing is maturing from idea to implementation, but we haven’t seen the paradigm shift yet on the street. Expect growing pains over the next two to five years as new development standards begin to produce more housing in different housing types in neighborhoods across the state. Hopefully, it will be accepted at scale soon enough to have an impact on Washington’s rising cost of housing.

Matt Hutchins is a co-founder of CAST architecture, serves on the Seattle Planning Commission, and is president-elect of AIA Seattle.

Other Stories:

- The need for high-performance building enclosure design

- Bypassing review to boost affordability

- Seattle’s commercial development at a crossroads

- Designing for health in affordable housing

- Disrupting inequality in housing

- Trends transforming life-science building design

- Eight trends shaping design for cities in 2024

- Centering the patient and community in rural healthcare design

- Engineering with support from the sky

- Transforming yesterday’s spec office into the destination workplace of tomorrow

- Designing library spaces for the children of today