|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Environment

| |

|

September 24, 2015

Drought heats up battle over water rights

Landau Associates

Easterson

|

In this land of “liquid sunshine” one might think access to water for potable supply, irrigation, hydropower and recreation is an inalienable right and abundantly available; but in reality, water is a limited resource and the systems in place for parsing out how water can be used are very complex.

Water is considered a public resource and the laws that govern water rights have been developed over time and are interpreted through administrative rules and a growing body of case law. So when water resources become stressed, as in this past year with drought conditions, determining who has priority rights for water use is a resource management challenge — particularly in rural parts of the state.

Much of that resource management responsibility lies with the state Department of Ecology, which makes determinations on applications for new water rights or changes to existing water rights. Water resources are also managed by the holders of water rights, such as municipalities or irrigation districts.

A number of recent clashes over water use have centered on the fact that water law was developed independent of land use law, causing disjointed and unclear procedures for growth and development in areas where water is in short supply. Growth planning, primarily a function of a county or municipal government, has been impacted in upper Kittitas, Skagit and Whatcom counties by litigation or new rules for managing groundwater resources.

When resources are abundant, we seldom consider who has priority rights for use because there is plenty to go around, but when resources drop below the need, rights to those resources are disputed and management strategies are critically scrutinized.

A changing landscape

Native Americans didn’t use the concept of water rights; populations were small and water was abundant. Water was simply a feature of the land that was used for crops, domestic purposes or activities associated with hunting and fishing.

With the onset of European settlement, but prior to 1917, pioneers who came west could establish a water right in one of two ways: by purchasing land with an adjacent stream or lake, which automatically gave them riparian water rights; or by finding the water they needed nearby, posting a notice that they were diverting the water for a beneficial use and thus acquiring the water through appropriation.

The system was chaotic and often fraught with the misconception that the owner of the land also owned the water, giving rise to water disputes.

In 1914, a report of the Washington Water Code Commission stated, “No state role in water rights led to water use that was not in the public interest.” So in 1917, Washington state adopted the Water Code to manage surface water use. From that time on, before using or diverting water from a stream or lake, one had to apply to establish a water right.

Today those applications are managed by Ecology, which determines whether to grant a water permit allowing the development of a water right.

A water right allows the holder to use water, but only to the terms and conditions specified in the document. These conditions must include a beneficial use, the place of diversion or where the water is sourced, an annual quantity which caps your use, a rate of use, and a description of where the water will be used. No one person or entity owns the water itself, just the right to use it for specific purposes.

The priority date system of assigning a senior water right is an enduring legacy from the days when appropriating water was as simple as posting a note on a tree or digging a ditch to divert water. Washington uses a “first-in-time, first-in-right” system for establishing senior priority to water usage. In times of water shortage, the senior water right holder can use or divert the full extent of the water allowed by their water right before the next person that chronologically applied for a water right could access any water from the same source.

Establishing water rights

Sorting out water rights can be a daunting task, and much of the challenge stems from the way in which those privileges were developed in history. A water claim (self-professed) and certified water rights (granted through application to a governing body after 1917) offer different documentation for water use. Early settlers believed that a water right claim was equivalent to a water right, but land uses changed over time and the original intent of a water claim might not exist, leaving little argument in favor of permitting a water right.

A water right can be challenged and subject to review by an agency or the court. Water rights can also be changed, but this exposes the documentation to investigation by Ecology for a determination as to the extent and validity of the water right. If Ecology finds that there is not adequate record of rights or that the historical use of the right is not consistent with the documentation, the water right can be modified, leaving the holder with less right to water use than was previously declared on paper.

A person can also lose a water right through abandonment or relinquishment. If the water identified in the water rights claim or certificate is not used or fully used over the course of five years, the portion of the right not used may be subject to loss.

Rights to groundwater use

With a growing population and an understanding of how surface water use is interconnected with the aquifer or groundwater sources, laws similar to surface water regulations were enacted in 1945 specific to groundwater. The key difference is an exception that under certain conditions a person can drill a well to extract groundwater without a water right permit for watering livestock, irrigating a non-commercial lawn or garden of less than one-half acre in size, and providing water for a single home, a group of homes, or a small industrial purpose — as long as the withdrawal is limited to less than 5,000 gallons per day.

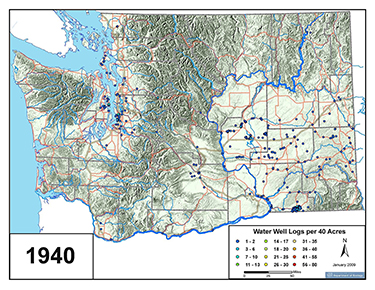

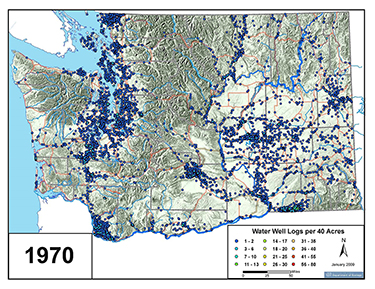

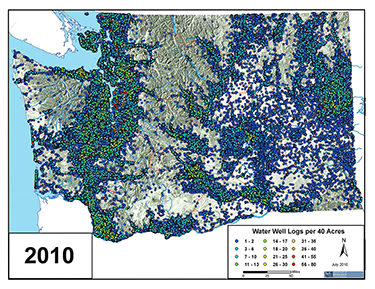

These exemptions were enacted with the belief that the uses of small quantities of water should not be subject to the full burdensome process of applying for a permit. Today, these exempt groundwater wells are one of the hotly contested issues over water resources management. There are more than 500,000 permit-exempt wells in Washington and most of them are not metered for water use, leaving a loophole for drawing more than the allowable limit of 5,000 gallons per day.

Some holders of certificated water rights are concerned that the growing number of wells will affect their ability to draw their full allotment of water.

Competing uses

Individuals are not the only ones vying for water rights; other competitors are municipal and industrial use, power generation, and with the adoption of the Minimum Water Flows and Levels Act in 1967 and the Water Resources Act of 1971, Ecology has had to balance the need for instream flows in addition to out-of-stream uses.

An instream flow is effectively a water right for a stream and applies a priority date just like any other water right. This means junior water rights can be suspended when stream flows fall below the established rule. Water rights pre-dating the instream flow rule are senior, but some instream flow rules do regulate exempt wells (such as in recent litigation in Kittitas and Skagit counties).

Residential development, encouraged by the county, cannot be approved for construction if water is not found to be physically and legally available. This puts agencies, typically tasked with growth, to share in the development of a water management framework that protects instream flows and senior water rights holders yet also allows for economic development, particularly in rural areas.

The legal requirement to not impair minimum instream flows and the resulting impact on water availability has sparked some of the most heated discussions over water availability and management. Some would argue that minimum instream flows are too complicated to assess and often result in requirements well above the reality of the actual stream flow. Other stakeholders make a strong case that instream flows alone don’t directly correlate to protecting the true health of a stream and that a net benefit approach that considers steam restoration strategies would result in both more water for out-of-stream uses and improved stream health.

On both sides of the debate there seems to be agreement that additional technical data and measurement would support better management decisions.

Seeking solutions

Ecology is engaged with stakeholders on all aspects of water resources, and has formed a Rural Water Supply Strategies Workgroup to help evaluate ideas for clarifying issues in water-limited areas. Working groups and stakeholder meetings have discussed how to better mesh development code with water law so that economic growth is not choked.

Strategies for measuring and assessing instream flows to maintain healthy habitats for fish and wildlife are being proposed and innovative ideas are being addressed for stewardship and management of existing resources.

John Thorson, who serves as a Federal Water Master in Washington state recently said, “Water links us to our neighbors in a way more profound and complex than any other.”

His words hold particular meaning as we collectively strive to find balance and seek solutions for Washington’s water needs.

Cindy Easterson is a senior marketing partner with Landau Associates, a firm that specializes in environmental remediation, environmental and geotechnical engineering, permitting and compliance consulting. Landau has offices in Edmonds, Seattle, Tacoma, Olympia, Spokane and Portland.

Other Stories:

- LID development training is a game changer here

- Survey: Shannon & Wilson

- Survey: Ridolfi

- Survey: Climate Solutions

- Survey: O’Brien & Co.

- Survey: Cascadia Consulting Group

- Survey: Golder Associates

- How deep green buildings can educate kids

- Here’s how to improve environmental health and safety

- New Ecology cleanup guidance: mirage or oasis?

- Kirkland taps county’s purple pipes for recycled water

- Designing infrastructure to combat climate change

- Building green? Don’t forget green financing

- Survey: Innovex Environmental Management