|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Environment

| |

|

April 25, 2024

Promoting residential adaptive reuse in Seattle through policy

Perkins&Will

Kleiner

|

Harrell

|

Grace

|

How can Seattle chart a course toward the city it aspires to become?

As we navigate our pressing urban challenges with opportunities for revitalizing our downtown core — re-purposing vacant office buildings and providing much-needed housing — we must also meet our city’s ambitious climate goals. By 2030, the city of Seattle aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 58%, with aspirations to reach net zero carbon by 2050. There is an opportunity to pair our city’s operational carbon focused policy with equally ambitious policies targeting embodied carbon. In fact, embodied carbon must be a part of the equation to meet our 2050 commitments.

By acknowledging and incentivizing embodied carbon reduction in reuse projects, we can power housing solutions and bring wind back into our sails for downtown development.

A NEW POLICY PROPOSAL FOR OFFICE-TO-HOUSING CONVERSIONS

Following other jurisdictions such as New York City and Pittsburgh, Seattle has made a commitment to converting underutilized downtown office buildings to multifamily residential use through land-use exemptions and the elimination of onerous code requirements. The city recently proposed an ordinance that has cleared the State Environmental Policy Act and is moving forward to the city council for a vote.

The proposed ordinance arrived on the coattails of the Seattle Office of Planning & Community Development (OPCD)’s 2023 competition, Office-to-Residential Conversion Visions for Seattle Downtown. In the Call for Ideas, Perkins&Will partnered with Unico to convert the Smith Tower to a mix of market-rate residential units, an informative experience that shed light on the potential costs for conversion: without additional incentives or reduced costs, office-to-residential projects are rarely economically viable. Many of the submissions proposed policy changes that would ease the burden of making adaptive reuse a reality, including grant money from the city, leniency in seismic requirements and reducing energy code requirements.

As a firm dedicated to building performance and Living Design , we’d like to shift the conversation from reducing energy code requirements to quantifying and capitalizing on embodied carbon reductions instead.

ADDING EMBODIED CARBON TO THE EQUATION

Embodied carbon, or greenhouse gas emissions caused by building materials, has not been as widely understood and measured as operational carbon, emissions resulting from running a building after construction is complete. Seattle has made commitments to reduce carbon emissions by a quickly approaching deadline, but the phrase “embodied carbon” is notably absent from the newly proposed ordinance. By adding embodied carbon savings to the equation, the city would not only bring our 2050 goals within reach but also benefit our frayed urban realm.

In recent years, Seattle has been quite active in reducing operational carbon emissions through strategy and policy. In addition to the city’s 2018 Climate Action Strategy , an executive order, Driving Accelerated Climate Action, was passed in 2021, further amplifying Seattle’s push toward net zero emission buildings. Then, last December, Mayor Bruce Harrell signed the Building Emissions Performance Standard (BEPS) into law, which requires existing buildings over 20,000 square feet to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to zero by 2050.

Over the next two decades, it will become easier to achieve operational carbon reductions. In 2019, Seattle passed the Clean Energy Transformation Act committing to a clean energy grid by 2045. Any building that transitions to all-electric systems will easily meet the operational carbon requirements. As operational carbon becomes less of a contributor to Seattle’s total carbon emissions, the significance of embodied carbon grows in proportion. A critical way of reducing embodied carbon is leveraging what we’ve already built. Adaptive reuse — adequately incentivized to developers and investors — is essential to meeting the 2050 deadline, as it avoids emissions associated with new construction.

Perkins&Will has completed a full life-cycle analysis on a range of projects, combining them into a benchmark database of embodied carbon emissions. The trend is clear: adaptive reuse projects’ average embodied carbon emissions are 42% less than new construction.

RESTORING VIBRANCY AND MAINTAINING CHARACTER

While not addressed in the proposed ordinance, Seattle’s existing urban fabric is part of what defines the character of the city. Imagine Seattle without buildings like Smith Tower dotting our skyline and shaping the streetscape. Transforming vacant office buildings to high-demand residential uses supports our 2050 carbon goals and maintains and improves our urban realm.

Thriving neighborhood districts rely on an active pedestrian environment and a mix of uses fostering a diverse mix of people and activities. Increasing the downtown population with more residential units will draw new retail and services, support existing retail and improve safety with eyes on the street throughout the day and night.

CARBON REDUCTION LESSONS FROM WEST COAST PROJECTS

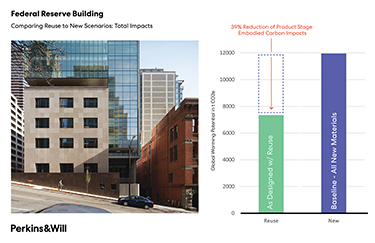

Narrowing our analysis from the broad benchmarking study to specific projects helps us better understand how to address embodied carbon and our historic urban fabric while not forgetting operational carbon. In downtown Seattle, the Federal Reserve Bank’s concrete structure and stone facade were retained while a new high performance office building was added above. In addition to reducing the total embodied carbon by 39% (compared to tearing it down and building new), the global warming potential of the concrete alone was reduced from 76% to 36%.

In contrast, the office building at 400 Westlake in Seattle’s South Lake Union neighborhood retained the facade of the old Firestone Tire building, while a new structure and high-performance enclosure were constructed.

This project focused on operational carbon benefits to achieve a net positive energy building generating 105% of the energy needed by the building and feeding the surplus to the grid. Solar panels were installed both on the roof and in northern Oregon where the electrical grid has more coal than Seattle. This resulted in an even greater operational carbon offset. Comparing these two Seattle examples, we see the value of tailoring design to a building’s specific reuse opportunities and a client’s carbon reduction goals.

A third example is the re-purposing of a 1929 historic tower at 100 McAllister in San Francisco. This project demonstrates how other cities are successfully implementing office-to-residential conversions while enhancing the urban fabric and user experience. Revitalizing the Great Hall, which has been vacant for over two decades, is a unique draw for prospective buyers to the 257 Class A residential units. Such amenities are uncommon in new ground-up buildings. Capitalizing on the unique benefits of adaptive reuse, the Great Hall is a differentiator in the market and contributes to the unique character of the neighborhood and city.

TODAY’S DECISIONS HAVE CONSEQUENCES TOMORROW

Our city is facing unchartered challenges that require the public and private sector to work together.

It is clear that adaptive reuse is a key strategy for reducing embodied carbon emissions with the added benefit of maintaining the vitality and diversity of our downtown. The OPCD’s Call for Ideas helped us realize that there are barriers to making adaptive reuse widespread in our city.

The proposed ordinance is a great first step, but by adding embodied carbon to the equation, we can further measure the city’s progress toward climate action goals, leading to incentivized adaptive reuse, while helping building owners meet their carbon commitments. As we prepare to ride the waves of unknown future policies, such as potential carbon taxes, our embodied carbon reductions today might become even more valuable in the city we aspire to become.

Devin Kleiner is a director of regenerative design and associate principal at Perkins&Will, leading sustainability initiatives for the Seattle studio. Myer Harrell is a senior regenerative design advisor and senior project manager for the Seattle studio of Perkins&Will. Elizabeth Grace is a senior project designer for the Seattle studio of Perkins&Will.

Other Stories:

- Creativity and innovation are hallmarks of sustainability at PDX Airport

- Curbing construction’s carbon impact from all angles

- Making old buildings new again: the case for adaptive reuse

- Hiding in Plain Sight: Sustainability and resilience beyond the terminal

- Reducing embodied carbon in concrete construction

- A blueprint for environmental responsibility in construction

- Old building, new tricks: Designing adaptive reuse for long-lasting relevance

- Harnessing the potential of mixed-use communities

- Implementing aggressive water goals

- Toward a path to zero carbon: building renovations and circular economy principles

- A primer on campus decarbonization in Washington