|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Special Issues

| special issues index  February 24, 2000 | ||

|

It�s an institutional game - or is it? The role of institutions in development seems to grow as the region - and the projects - grow too.

By MARC STILES There�s no disputing that developing marquee projects is a daunting task. It requires not only expertise but access to boatloads of capital. In the last 10 or so years, the work has become even more complicated, with a spate of new regulations. And, after the last disastrous market bust, financiers understandably have become much more picky about which projects they will back. The result has been an upswing in activity by bigger players, namely institutions. Many developers in the Seattle area agree that the roles of institutional players will continue to expand. That�s because the size of the market has grown, as has the scale of projects. This is not to say that the days of lone-ranger developers are over; privately held Seattle companies headed by individuals, such as Martin Selig, prove that. But those familiar with commercial development in the Puget Sound region have observed that the power of institutions is growing. Consider recent moves by Equity Office Properties Trust and Cal West. Equity Office is the nation�s largest real estate investment trust, or REIT. (REITs are required by federal law to pay virtually all their taxable income to shareholders and may deduct the dividends paid to shareholders from their tax bills.) Earlier this month, Equity Office agreed to a $4.6 billion deal in which Cornerstone Properties Inc., will merge into Equity. The transaction will increase Equity�s national portfolio of 77 million square feet by 24 percent. In the Puget Sound-area the merger will boost Equity�s 5.4 million square feet by about 17 percent. This surely will make it easier for Equity to develop with Wright Runstad & Co., its partner in the Northwest, an estimated 600,000 square feet of office space on the City Center II site Equity owns in downtown Bellevue.

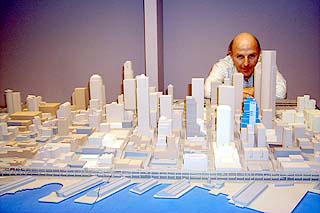

Spieker�s plan is to use the capital to focus more on the Eastside suburban office market. The REIT already has bought several office trophies, such as Eastgate Office Park and Lincoln Executive Center, and Bellevue City Hall officials say they met recently with Spieker representatives to discuss the company�s plans to build an office tower of up to 20 stories in downtown Bellevue, on Northeast Eighth Street between 108th and 110th avenues northeast. The common thread here is that all the players involved in these deals are institutions. "The nature of the business has changed radically," said Gary Carpenter, who heads the U.S. division of the publicly traded Bentall, a British Columbia company that is active in the Seattle and Los Angeles markets. It�s very difficult to finance projects and it�s very tough for individual entrepreneurs to raise the necessary capital to build even a medium-sized project, he said. Carpenter speaks from experience. He and a former partner, Dick Clotfelter, ran a development company, Prescott, that closed after banks shut off the flow of capital to builders when the bottom fell out of the real estate market a decade ago. Now, however, he�s with a larger, publicly traded company that can use its own credit and sell its own properties to move in and take advantage of opportunities. "It�s really an intuitional game," Carpenter said. Certainly, some of the developers who were around for the last wave of development are still here today. But, as Carpenter said, he and others have "different sponsors." Various developers say Wright Runstad & Co., is a prime example. Selig, one Seattle developer who did survive on his own, said Wright Runstad "is now a developer for Equity Office," which about two years ago paid $610 million - plus $15 million in transaction expenses - for eight Wright Runstad buildings in the Northwest. Chairman and Chief Executive Jon Runstad said it�s not quite right to say his company now is merely a developer for Equity Office. Equity has a minority and non-controlling interest in Wright Runstad, said Runstad, who added, "Equity is not involved in everything we are doing." According to Selig, who has built millions of square feet of commercial space, development today does not necessarily belong only to institutions. "I built all these things without a partner," he said. Being independent helps, he said, because he can buy and sell quickly and not have to wait for the OK from a home office in another city. "I think the players that have really been the builders of the Seattle and Bellevue skylines will always be prominent forces," said Tom Parsons, vice president of Opus Northwest LLC. "They have the connections that will continue to allow them to be a very competitive force." Cabot Cabot Forbes and other big players left the Seattle market in the 1980s. "The local guys didn�t and most of them have survived," Parsons added. "They�ve been successful in the upturns and the downturns. It�s the local guys that have the vision that sometimes the institutions might not." This is not to say that institutions will not play an ever growing role in the market. As the region�s population inches closer to the 3 million mark, Parsons said, investors have taken notice. The growing population has put the region on the radar screens of institutional buyers. The size of the market has grown and deals today are more costly and complicated, giving institutional buyers an advantage. "But in reality, the A team of developers that have built this city, I wouldn�t bet against them," Parsons said. Greg Smith, principal at Martin Smith Real Estate, a family-owned company, agrees. He does not, however, dispute the growing importance of bigger organizations. "I can only speak from our own perspective," he said. "We are busier than we�ve ever been. And we�re growing. As we grow it�s easier to do stuff on our own." Still, he thinks the trend is toward more involvement by institutions. "If you don�t have a machine behind you, I don�t think you can do it," said Smith, who, like Carpenter, speaks from experience. Last year, Martin Smith Real Estate sold to Hines the building site for the 810,000-square-foot Madison Financial Center in downtown Seattle. "At the time we would not have been able to do that on our own. It�s a $200 million project," said Smith, whose company is assisting Hines on the project by providing its hometown knowledge. Like Martin Smith, Hines is a privately held family operation so it is not an institution per se. Hines has development funds totaling $5 billion, but it too is working with an institution on Madison Financial Center. The project is being financed by National Office Partners Limited Partnership, a joint venture between Hines and Cal/PERS. For Runstad, it�s not a matter of entrepreneurs vs. institutions. The composition of the development community remains very much the same with a mix and match of institutions and individuals, he said. "It�s the market that�s different," he said. "We�ve never experienced a market with this kind of growth, a market with this much demand for space."

|