|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Architecture & Engineering

| |

|

July 26, 2012

Tight UW site left nowhere to go but up

NBBJ

Duff

|

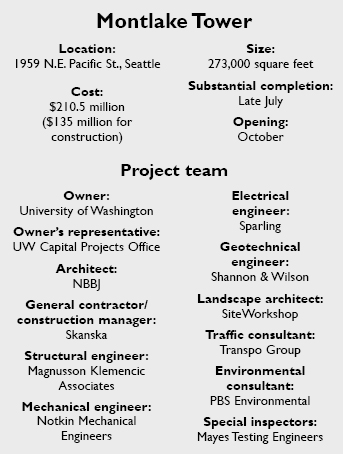

The University of Washington Medical Center will take a step forward this October when it opens the 273,000-square-foot Montlake Tower expansion.

The project is the largest addition to the medical center in decades, and it increases the hospital’s capacity to treat a variety of patients.

The design process met a variety of critical challenges to construction.

UWMC first identified the need for an expansion of this size and scope in 2005 after commissioning a study to determine how to best optimize its existing space. That study culminated in a two-part plan: renovate existing space to create better patient outcomes, and create a new facility — the Montlake Tower — to increase capacity and the hospital’s ability to care for patients and staff.

Since then, the challenge became not whether to build but where to build.

The medical center is located at the southernmost edge of the university campus, along the Montlake Cut. With literally no room to expand horizontally, NBBJ and the UWMC decided to expand upward by temporarily relocating a loading dock and building the new tower in its place.

To keep the hospital fully operational during construction, the project team developed a logistics package that accommodated alternate loading facilities as well as patient, visitor and adjacent campus traffic.

Height constraint

Early in the design process, the project team faced a major constraint: the 12-foot floor height of the existing 1959 hospital. Building the expansion at the preferred 15- to 18-foot floor height for new hospitals would reduce the number of floors due to zoning height limits, and would require ramps to the existing hospital on several floors — an undesirable outcome in providing seamless patient care.

The solution: Convert the entire third floor to mechanical space and align all the other floors to the existing hospital. This floor relies on vertical shafts to support the imaging and operating room suites on the second floor and the patient floors above, thus reducing overhead ducts and maximizing the ceiling height.

This solution required close collaboration between the designers and the construction team, made possible by using the general contractor/construction manager process, which brings the general contractor on board early in the process to comment on phasing, logistics and design decisions.

Three-dimensional modeling of major components and systems allowed the project team to resolve potential conflicts before actual construction began. Even while the new tower steel was going up, a physical mock-up of the patient rooms was built to ensure that all the subcontractors understood the physical constraints and phasing necessary to build patient rooms in a new building with limited height.

Letting in light

Now nearing completion, the Montlake Tower continues a precedent set with the last major building built on campus by providing daylight, views and connections to the outdoors.

Long hallways and other circulation spaces all have access to natural light, either along the corridors on the surgery and imaging level, or at the ends on the patient floors. This connection not only creates a welcoming environment, but also helps orient patients, visitors and staff as they move throughout the hospital.

Connections to nature continue inside the new patient rooms, which all feature expansive glass along the exterior walls. The new south-facing rooms are oriented to maximize solar shading and views of the water and Mount Rainier, while the new north-facing rooms, as well as half of the existing patient rooms, overlook a newly landscaped courtyard. The patient-room floors connect seamlessly to the existing hospital at each end of the new tower.

Of course, for patients, the most important feature of the Montlake Tower is the care it provides. One of its most exciting services: 47 private neonatal intensive care units, constituting the largest facility of its kind in the Pacific Northwest.

This design reflects a growing body of evidence that shows babies recover faster from critical illness when they are placed in an environment void of bright light and loud noises, as opposed to a more traditional unit that might group as many as a dozen infants in a single room.

In addition to the direct medical services the facility will provide to patients, the Montlake Tower project will become one of the most energy-efficient hospital additions in Pacific Northwest history. Energy strategies — which include the use of heat-recovery chillers, the reorientation of patient rooms with solar shading, and the use of LEDs for patient-room lighting — will save UWMC approximately $550,000 in energy costs annually.

And there’s more ahead: To accommodate further growth on the tightly constrained campus, the project provides shelled future expansion space for two more MRIs and up to eight operating rooms, as well as three more floors of patient rooms for either 24 intensive-care unit beds or 32 medical beds on each floor.

An expansion with a big impact for UWMC, the Montlake Tower will provide state-of-the-art care for years to come.

Phil Duff is a principal at NBBJ, an architecture and design firm ranked as the second largest health care design practice in the world by BD World Architecture.

Other Stories:

- Lean design is different for every health care project

- Simulations playing wider role in nursing education

- Former TV studio remodeled into dialysis clinic

- Silverdale hospital sets ambitious budget for new wing

- Virtual tools put Everett tower on the fast track

- Clinic designs evolving to meet growing list of needs

- Hospital’s mechanical design process a complex dance

- When hospitals expand, traffic concerns follow

- Builder’s challenge: Keep UW hospital running smoothly