|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Architecture & Engineering

| |

|

|

Design Perspectives By Clair Enlow |

November 27, 2002

New urban design challenges ride in on monorail

Special to the Journal

With our dense population of planners and design types, it's my guess that transportation problems and transit solutions have gotten more hours of debate, analysis and design in Seattle than any other city in the nation or even the world. The public has been invited to workshop after workshop, and they’ve been asked to vote and vote again.

Through it all, the great question on the mind of every civic soul is: What should we do to meet the region’s increasingly desperate transportation needs?

Sound Transit was supposed to have the answer. And after many delays, cost overruns and design controversies, light rail seems to be grinding along to a truncated reality. But the imagination of the public -- never a reliable energy source -- is flagging badly. And trust has suffered severe setbacks.

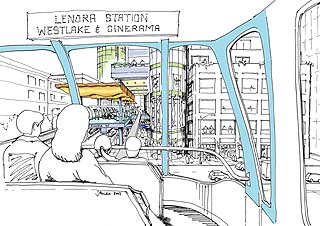

Renderings courtesy of Cascade Design Collaborative This view of a prospective monorail station at Second and Lenora shows how new development can be incorporated into the system. Access to the platform is part of the vertical circulation of the building (glass corner, right). |

Then this month, a narrow majority of voters stepped in and supplied a transportation answer of their own: monorail. The Seattle Popular Monorail Authority, an activist organization turned public works administrator, has their trust.

And now, as architect and urban designer Lee Copeland so succinctly puts it, "It’s time to re-think the question."

Scratch "What should be done?" What we really want to know is, "What can be done?" More specifically, what can be done for a predictable cost? Something that won’t strain the credulity or the limited attention span of the electorate?

When the question is framed this way, the logic of monorail is easy. Speed and constructability win hands down. The riders it will serve in the next 10 years are eager to ride, and they approved it.

Based on voting patterns and expressed support, the $1.75 billion, 14-mile Green Line and its 19 stations will be embraced along the route. If it all works according to supporters’ predictions, riders will follow rapidly, and so will support for expansion, four more segments reaching all over the city.

There’s no thicket of federal hoops and hurdles. The board is home grown and thoroughly engaged. Board members and consultants insist that the monorail is not meant to compete with light rail lines for resources or public support, and will become a part of a mass transit network that includes both systems. But they say they have learned from the mistakes of Sound Transit.

Now that the question has been re-framed, there are still a lot of answers to come up with.

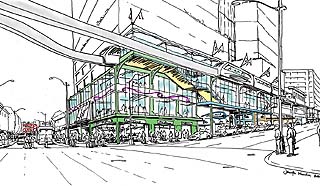

Seattle's Green Line will be a singular example of monorail among high-rise buildings. Backers have assured voters that concrete columns of the new system will be narrower and further apart, and the guideway will be higher off the street. |

Certain basic components of the system will be determined through the choice of a single design-build contractor, possibly as early as next fall. But aside from the cars, the guideway and the electronics that drive the system, there are many questions about the monorail that are yet to be answered. And these questions deserve the broadest perspective and the best possible design sense and judgement.

As early as Dec. 13, the SPMA will select a design firm to help answer them. A request for qualifications is now available.

Architect Donald King, who is on the interim board, said that making sure there is a design lead independent of the monorail design-build team is very important. And he hopes that some skeptics and critics will add their input now -- if not as part of the design team, then as citizens of their own neighborhoods.

"That’s where the integrity of the architectural profession will come in," said King. "I hold onto that optimism."

The monorail plan we voted on leaves many urban design questions to be resolved.

"We drove the design as far as we could to get a cost model," said Eric Schmidt of Cascade Design Collaborative, which assisted in developing a plan for the monorail as a subconsultant to Berger/ABAM Engineers, and generated sketches of downtown stations.

The final design will be driven by a number of urban design issues in and around downtown Seattle. They include:

Stations along the new Green Line will be designed by firms picked location-by-location. The design lead will help shape the scope of their work. |

Alignment. The route has been more or less determined by the plan that was submitted to voters this month.

The devil is in the details. What downtown windows will be rattled and what occupants startled by the passing of the train? Where it will skim a historic facade or cross the street instead? How it will converge and diverge with the pavement as it meets Seattle’s hills and passes from downtown high-rises to neighborhood centers? Will it whoosh right over the heads of pedestrians in some places or soar to thrilling heights?

Left alone, engineers and rail systems builders would supply answers to many of these questions. Feasibility, cost, and traffic concerns will have a great deal to do with alignment, as will partnerships with private property owners who are willing to work with the SPMA to integrate stations into their construction plans.

Monorail backers have promised possible spans of 120 feet, between columns that are only 3 feet in diameter. But the ultimate impacts of the system will have a great deal to do with the exact placement of the columns on the streets and sidewalks. A number of calculations, with design lead input, will determine exactly where the paths and views of pedestrians are blocked -- and how much they are worth.

One of the potential ironies of the monorail plan is that the Green Line, as now routed, may mean sacrificing the 1962 monorail, skirting around Seattle Center and abandoning the EMP, a building designed around the tracks of the monorail. Most of the old line could be kept -- adjusted in places for tandem alignment -- but there would be very difficult urban design issues involving trains on two levels along Fifth Avenue.

Station location and design. According to the plan currently in place, there will be 19 stations on the Green Line. But their actual locations will determine much about the way they meet and relate to the street. Circulation, pedestrian amenities and visual character are among the many variables that the design team will begin to address. A series of neighborhood meetings in January will provide input for the board and the design team.

Ultimately, design of the stations will be undertaken by firms picked location-by-location, and the design lead will help shape the scope of their work. The design lead will also drive decisions about how many pieces of the stations -- platforms, stairs, elevators, escalators, mezzanines, canopies -- will be chosen from a "kit of parts," unifying design elements for all.

Much of the old monorail line would be kept, and adjusted in places for tandem alignment with the Green Line. |

Rail support structures and bridges. The framers of the monorail plan have taken great pains to minimize the bulk, shading and view-blocking dimensions of the system. But the 30-foot-high,3-foot-wide columns and beam support elements that will run along Seattle streets should not escape the scrutiny of urban designers. The shaping and finishing of the concrete and steel elements will help determine the impacts of the system. If Seattle is going to be the first city to bring a monorail through its heart, there are certain responsibilities involved.

The Green Line’s two water crossings -- over the Lake Washington Ship Canal near the Ballard Bridge and over the Duwamish, perhaps in tandem with the West Seattle Bridge -- will provide great opportunities for synthesis of structural engineering and design. Inspiring models for visually exciting industrial structures should be sought out and studied. Other special structures will support the guideway system in certain areas where it must rise 60 feet above the ground. In some places, a "straddle bent," or U-shaped support for the guideway, must be used so that traffic can flow beneath.

Ancillary structures, including maintenance facilities and power substations, will need to be placed along the guideway. In a dense, urban setting, even these small additions have impacts.

In a city increasingly conscious of historic preservation, the monorail is a modern solution that is intrusive and potentially oppressive. But SPMA interim board vice-chair Kristina Hill hopes that Seattle will accept elevated transit as a rational 21st century solution to a very real problem. And she reminds us that elevated rail is an integral part of vibrant older cities like Paris and Berlin.

When Seattle’s first monorail began nosing through the city just in time for the Seattle World’s Fair -- it was an exciting vision of the future, and a solution to a problem that did not yet exist. While the monorail may not be the solution to our transportation problems, it will be a fun ride. And it may keep hope alive.

Clair Enlow can be reached by e-mail at clair@clairenlow.com.

Previous columns:

- Neighbors gather to transform, uplift Courtland Place, 10-23-2002

- In Cuba, the future of the past seems assured, 09-18-2002

- Local designers expand vocabulary of architecture, 08-21-2002

- A/E diversity means freedom to pursue dreams, 07-17-2002

- Today's land use rules give as well as take, 06-26-2002

- Can art be the basis for expanding architecture?, 05-22-2002

- Community design movement comes of age, 04-17-2002

- Home is where the park-and-ride is, 03-20-2002