|

Subscribe / Renew |

|

|

Contact Us |

|

| ► Subscribe to our Free Weekly Newsletter | |

| home | Welcome, sign in or click here to subscribe. | login |

Construction

| |

|

October 6, 2022

Centering community for a transformational result

McGranahan Architects

Bose

|

Fields

|

The built environment sits at the intersection of creativity and justice. How do we build a world together that serves the needs of all, and who gets to be involved in the planning process? Many public institutions are rethinking their relationships to the vibrant communities they serve, particularly those who have historically been marginalized. Each new endeavor is an opportunity to right injustices, offer a degree of healing, and center the wisdom of those less seen or heard.

In 2020 the city of Tukwila, a majority-minority community with a large immigrant and refugee population, identified the need for an intergenerational center to serve adolescents and older adults. The community recognized that many teens and older adults would thrive with culturally relevant programs providing opportunities for engagement, education, and support.

Our project team sought to move beyond transactional relationships by creating a process to lift up the collective experiences and expertise of the community. This transformational process centered community as expert, allowing the project team to play a supportive role in applying the community’s skills and knowledge to amplify their concepts, ideas, and aspirations.

The following key principles of our process were foundational in building a vision for the new Tukwila Teen & Senior Intergenerational Center:

1. Establish an appropriate timeline and revisit as necessary. Transformative community engagement takes time. The full process took nearly a year, with three months of crafting the process, about seven months of community engagement, and two months to complete the report and deliver it to City Council, who had been receiving regular updates throughout the process.

2. Assemble a responsive project team and establish decision makers. To build with community, we can only build at the speed of trust. Transparency builds trust. Community needs a responsive and accountable project team guiding the process, and community must know who the final decision makers are to understand their agency in the process.

The project team consisted of the deputy city manager/co-project manager, Rachel Bianchi, the city’s teen center director/co-project manager, Nate Robinson; SOJ project managers experienced in the Tukwila community; community engagement advisors, Bookie Gates, Gates Ventures Group, and W. Tali Hairston, Equitable Development LLC, with the expertise and lived experiences to bring meaningful insights to the process; and a multi-disciplinary team of design professionals including McGranahan Architects, Site Workshop, and Jacobson Consulting Engineering. Together we created an engagement plan, including progressive implementation of activities based in and responsive to consistent community input, that centered the relationship between the city and the community.

The project team clearly communicated that community input was advisory to the City Council. Community was encouraged to “dream big” as they lead the team in studying site alternatives and imagining what activities would be offered, while understanding that City Council would make the final decision. Community members learned about the design and construction process and advocated for themselves at council meetings.

3. Build community awareness and develop direct community relationships. The project started with a goal to reach out to as many residents as possible. The objective was to create relationships that would not only sustain the subsequent funding, design, and construction phases, but would also establish an already thriving culture for the new facility when it opens. To do this we conceived of three phases of community engagement — a robust initial outreach through many small group meetings, in-depth Champion workshops, and full-community verification steps.

For the initial outreach, the project team brainstormed over 50 community organizations to establish relationships with. Conversations were guided by eight questions to provide context and gather community stories around an intergenerational center and ask if there were any other concerns the city could address.

These small group meetings allowed the city to establish authentic relationships where residents were able to learn about the new project, provide their lived experience, and understand how to further engage with their city officials. The project team collected hundreds of data points from these conversations that were distilled into nine different categories: Diversity, Learning, Activities, Atmosphere, Wellness, Food, Outdoors, Exercise, and General Thoughts. These categories became the basis for the Champion workshops phase.

4. Center community as leaders and experts. The city identified 23 Community Champions, representing the broad diversity of Tukwila, to develop the initial small group engagement. Champions were asked to represent, engage, and advocate for the wants and needs of all Tukwila. Champions were compensated for their time and contribution.

Each meeting or workshop was conducted on three different days and times to accommodate the schedules and personal commitments of the Champions. This added complexity to the planning and required more time, but the inclusion of all perspectives was invaluable in building a vision.

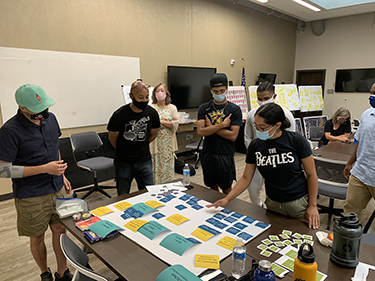

The visioning process was intentionally iterative. Each engagement with Champions voices formed the foundation for each subsequent step. Each meeting began with the confirmation, “Did we hear you?” and “Does what we have collected resonate with you?” Only when we had recorded observations and concerns, and had received affirmation, would we continue. Through a series of workshops, the Champions collected and prioritized spaces, relationships, and activities that formed the basis for the full program included in the project proposal to the City Council.

5. Sharing information and key decisions with community for verification. The project team clearly articulated expectations, project understanding, community responsibility, and next steps at every engagement opportunity. The city employed a variety of communication methods to report and verify the information gathered with the whole community: a website, survey, and mailer in multiple languages and several in-person and virtual town hall meetings where the overall Tukwila community added their voice to the mix. Key decisions were consistently shared back in a timely manner by the city and supported by the cultivated network of relationships that were formed or strengthened during the community engagement process.

Both large and small group community meetings allowed deeper conversations between the project team and the community, leading to more authentic relationships and a deeper project understanding on both sides. We held multiple sessions of each meeting or workshop to accommodate a variety of schedules among community members. In all, the city led 68 meetings through the three stages of engagement — initial outreach, Champion workshops, and verification steps.

RESULTS

Transformational community engagement requires a level of care, empathy, commitment, and follow-through that must consider the lived experiences of those we wish to serve. For many in marginalized communities, participation in a process that asks about their needs is a reminder of injustices, past and present, that they have experienced. Asking for them to be vulnerable enough to share their aspirations is a reminder of times their hopes have not been met.

Participants offered their experiences of joy in their cultures, pride in their diversity, and their connections as a community. The community expressed that they felt a sense of partnership as they engaged in this inclusive process with the project team. The relationships formed are authentic and community members expressed they felt heard even through challenging conversations.

For the Tukwila Teen & Senior Intergenerational Center this process has been a first step. We hope to inspire others to build upon the meaningful lessons that we took from this project as they conceive of future projects that serve their communities. Each new project holds unique opportunities to enhance and strengthen “institution to community” relationships. By committing appropriate time and resources to this process, and by developing a transformational mindset towards community relationship building, the city of Tukwila offers an example of design engagement for public institutions to thrive.

Shona Bose is the director of environmental responsibility and a staff architect, and Ben Fields is a partner and project designer at McGranahan Architects.

Other Stories:

- Design can influence beyond its borders

- The next great environment for schools

- K-12 alternative delivery is here to stay

- Teamwork creates modern, flexible spaces to learn

- Here’s how to decrease carbon emissions in schools

- Feasibility and design in early learning education

- Designing a co-location campus

- Building resiliency at University of Washington